16 history museums get their stolen guns back

Law enforcement spent 14 years hunting for 36 historic guns stolen 50 years ago — they turned up in Newark, Delaware.

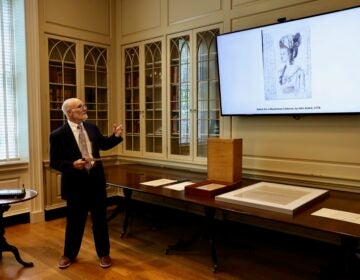

Fifty artifacts stolen from museums and historical sites 50 years ago were returned to their owners during a repatriation ceremony at the Museum of the American Revolution. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Fifty stolen historic objects — most of them antique guns dating to the Civil and Revolutionary wars — were reunited with sixteen museums from which they were stolen half a century ago.

In 2017 the FBI’s Art Crime Team and local law enforcement arrested Michael Corbett for possessing dozens of historic guns stored in Newark, Delaware. Corbett admitted to possessing a trove of objects that had been stolen between 1968 and 1979, from small museums and historical societies throughout Pennsylvania, and as far away as Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Assistant U.S. Attorney K.T. Newton said there is a strong likelihood that Corbett stole the objects himself.

“That’s the crime that we wouldn’t be able to prosecute, the theft, because of how long ago it was,” she said. “But it is a crime to possess objects that were stolen and have been transported interstate.”

Corbett, who cooperated with detectives, was sentenced to one day in Federal prison and three years of house arrest.

Detectives worked 14 years to crack a case so cold it had itself become a piece of historic lore.

Valerie Seiber, collections manager at the Hershey Story Museum, recalled getting a phone call out of the blue from Detective Brendan Dougherty of the Upper Merion police, asking about a theft that occurred more than 50 years ago.

“How did he know?” Seiber said. “That was our dirty secret.”

Ultimately, Seiber got back something she never knew the museum had: a Volcanic pistol engraved with the name of a Civil War soldier from Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood.

“In fact, I’ve never even seen a photograph of it until about a week ago,” she said. “I’m no expert in antique weaponry or Civil War history, but I do know a good story when I hear it.”

In 1861 that soldier, Lieutenant Christian Schaeffer, 24, joined the regiment of Colonel Edward Baker, who would become the only sitting U.S. Senator to die in combat. Schaeffer survived the defeat at Ball’s Bluff that killed his leader, but later died from typhoid fever in an unsanitary army camp.

“Returning this pistol to the Hershey Story Museum, and the public trust, allows us as museum professionals and storytellers to share our nation’s history, both the good and the bad, with our visitors,” said Seiber.

The FBI occasionally hosts repatriation ceremonies wherein victimized institutions take formal possession of their stolen property, but the ceremony on Monday at the Museum of the American Revolution was unusual for having so many artifacts — 36 guns and 14 other objects — going to so many recipients.

A previous repatriation ceremony hosted at the museum in December 2021 was uncannily similar: a cache of antique guns stashed in the Philadelphia region, that had been stolen by a single person from Pennsylvania historical societies in the 1970s.

Scott Stephenson, president and CEO of the Museum of the American Revolution, said the two cases are not related.

“They are literally only related as it was two people kind of doing the same things: stealing historic firearms from small museums in the late sixties, early seventies,” he said.

Newton, of the U.S. Attorney’s office, said there was a spate of similar thefts throughout the 70s.

“There were at least 4 to 5 thefts from Valley Forge [Historical Society] between the late sixties and 1979,” she said. “Hopefully those things don’t happen today. We have better security.”

Why were there so many thefts within that window of time? Stephenson believes it may be related to the public hype at the time surrounding the United States Bicentennial.

“There was all of a sudden a lot of interest in these things, and maybe organizations were bringing more things out because of perceived public interest,” said Stephenson with a shrug. “Or, maybe there were sunspots. I really don’t know what it was. I was only 10.”

Stephenson said that, back then, smaller museums that were largely volunteer-run were more vulnerable to thefts because they did not have budgets for enhanced security or for keeping adequate documentation of their inventory. If an object disappeared, there was little they could do to hunt it down.

He said museum practice now has become more professionalized, making theft harder and recovery easier.

Researchers at the Museum of the American Revolution assisted FBI detectives to identify the guns discovered in Corbett’s stash and where they might have come from. Some of the individual objects had already been photographed and documented in 1967 for George Neumann’s “The History of Weapons of the American Revolution,” a book Stephenson poured over as a child, already a precocious scholar of the Revolution.

Among the stolen items returned were five Kentucky flintlock long rifles taken from the Blair County Historical Society; pistols stolen from the U.S. Army War College Museum in Carlisle, Pa., that had belonged to Omar Bradley, the World War II general and the last U.S. general to achieve the 5-star rank; and an early pistol prototype manufactured in the mid-19th century at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts.

Alex MacKenzie, a curator at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site, said the pistol was designed with a revolutionary idea of the time: interchangeable parts for mass production. It is the 12th of only 12 made.

“This was made by Springfield Armory as a pattern pistol. What that means is it was made for contractors to use,” he said. “It was a blueprint before blueprints existed. Springfield Armory had such an important role in figuring out interchangeability, which was the seeds of the Industrial Revolution.”

The Museum of Connecticut History arrived in Philadelphia with two Connecticut state troopers to make sure its 1847 Colt Whitneyville Revolver made it back home safely. The historic gun was designed by Connecticut native son Sam Colt, and was one of the first factory-made revolvers in Colt’s storied career of firearm invention.

Museum of Connecticut administrator Jennifer Matos said the process of tracking down the stolen guns and finding out from which museums they came is worthy of history books.

“It really is kind of miraculous,” she said. “I hope they write a book or make a movie about this.”

Stephenson concurs.

“Absolutely,” he said. “I hope they get Harrison Ford to play me.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.