City Council is proposing a parking tax increase. What would that mean for urban development?

City Council unveiled its alternative to Mayor Nutter’s proposed budget this afternoon, and in an interesting turn of events, it contains a parking tax increase.

The three bills that make up the funding package, introduced by Councilman Bill Greenlee, raise an estimated $70 million–much lower than the School Reform Commission’s $103 million ask–by increasing property taxes, but also Use & Occupancy taxes and parking taxes. Holly Otterbein reports that Council is aiming for around $80 million.

The parking tax would be increased to 22.5%, from 20%, and raise a projected $10 million. For context, that’s still higher than New York City’s parking tax, but lower than Pittsburgh’s 40% parking tax (which once was 50%.)

As I noted a few weeks ago when At-Large Council candidate Helen Gym first proposed a parking tax increase in her plan for more local school funding, this is a pretty significant reversal in the recent political trajectory of the Philly parking tax.

Not too long ago, a parking tax cut seemed to have the political wind in its sails. Michael Nutter raised it from 15% to 20% in 2008, and it’s remained there ever since. Naturally, parking companies have been lobbying ferociously to lower it, and they got close in 2011 with a bill sponsored by then-Councilman and now Democratic Mayoral nominee Jim Kenney, but Michael Nutter vetoed that, questioning its budget math.

Nonetheless, the odds seemed good that parking taxes would eventually get cut, or at least not be raised again.

And then, just like that, At-Large Council candidate Helen Gym started talking about raising the parking tax during this year’s campaign, went on to win one of the five Democratic At-Large Council seats, and suddenly incumbent City Councilmembers feel comfortable talking about another increase.

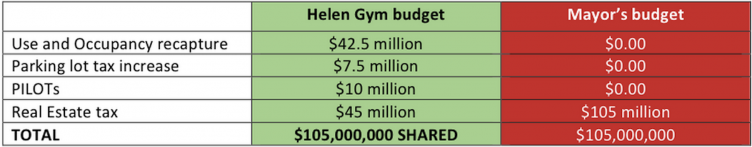

Interestingly, the Council proposal actually goes further than Gym’s plan. Gym would have raised $7.5 million, and Council’s bill raises $10 million.

Councilman Greenlee told Otterbein he is just putting all the options on the table, and says the exact revenue mix could change. The Philadelphia Parking Association is hoping that will be the case, and are already lobbying hard against the proposal, denouncing it as a job killer.

What would be the impact of the parking tax on the built environment, or Philly’s economy in general? Once again, here are the key passages of the analysis Econsult prepared for the Parking Association (my bold):

In the short run, a change in the parking tax has no impact on the parking rates paid by the consumer. Consequently, the parking facility operator pays the entire amount of a parking tax increase. Parking facility operators face the same short run problem every day – how to maximize revenue. In other words, parking operators are already charging as much as they can and the price consumers pay is determined by the number of spaces and the demand for parking, not by the level of taxes. The level of taxation and the other costs of operating a facility do not affect the price charged or the number of spaces available unless the costs are so great that the operator shuts down the facility.

In the long run the story is quite different. An increase in parking taxes discourages the rejuvenation of aging facilities, the replacement of facilities lost to development, and the construction of additional facilities. Thus higher parking taxes will decrease the long-run supply of parking, will increase the cost to the public of parking, and will decrease profits to owners of parking facilities. Further, should an additional parking facility be required, a higher parking tax implies that the facility will require larger subsidies to develop than it would in the absence of the parking tax increase.

Depending on your view of the importance of cheap and abundant parking for commuters and visitors (and healthy profit margins for parking facility owners) increasing the long-run disincentive to use urban land for parking facilities is either a feature or a bug.

Pittsburgh’s experience with confiscatory levels of parking taxation (and land taxes) offers some interesting evidence that Econsult analysts are right, and the economics favor more mixed-use infill development and less parking development on high-value central land. That’s bad for incumbent parking business owners, but good for real estate developers and their eventual tenants, and ultimately good for the city budget as property tax abatements expire.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.