Cancelled speaker at Friends Central the latest in a spate of on-campus free speech controversies

Friends' Central School in Wynnewood. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Sa’ed Atshan is a popular professor at Swarthmore College.

How popular?

Although he joined Swarthmore’s faculty just two years ago as a visiting professor, hundreds of students pack his lectures, film screenings, and annual trips to Israel/Palestine. Hundreds more signed a petition last year to ask administrators to give him tenure so he could stick around longer.

Yet to administrators at Friends Central School in Wynnewood, Atshan poses such a “concern” that they canceled his scheduled speech at the Quaker school last week. Students and parents had complained about Atshan’s ties to the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, a global campaign against Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories in the West Bank.

But the cancellation sparked big-time backlash: A mass student walkout last week, the indefinite suspension of two teachers deemed disobedient, cries of censorship, and threats from disgruntled alumni to withhold support until the school apologizes and reschedules Atshan’s talk.

To many, Atshan seemed an odd speaker to silence. He’s a longtime Quaker with Ivy League credentials who teaches peace and conflict resolution and specializes in nonviolent social movements.

But he’s just the latest in a “disinvitation” epidemic that erupted when people — fired up by an incendiary presidential race — responded to the rhetoric by covering their ears to shut out opposing viewpoints, according to the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), a national, nonpartisan nonprofit that tracks such speaker cancellations.

“The heat of the election season raised the temperature and made people a little bit jumpier. We’re in a very raw national mood right now,” said Ari Z. Cohn, a FIRE attorney. “We’re seeing a retreat back into echo chambers, where the only people we listen to are the people we agree with.”

Invitations to 43 speakers were withdrawn or threatened last year, up from 21 the year before, according to FIRE, which was cofounded by a University of Pennsylvania professor and is based in Old City. The group has tallied more than 330 disinvitations since it began tracking them in 2000, according to its online database. And there already have been a few cases in 2017, including Fox News contributor Juan Williams, who Ursinus College this week decided wouldn’t be in the running as commencement speaker after faculty at the Montgomery County school objected.

FIRE focuses on college campuses, because they’re revered as havens of intellectual diversity, where students are adults and have the option to not listen to speakers they don’t want to hear. Lower schools, conversely, have a captive audience of underage listeners, so school administrators rightly have more factors to consider when hosting speakers, Cohn said.

Still, silencing speakers — no matter the age or circumstance of the audience — provokes the same concerns, he added.

“It’s troubling when students don’t believe that there’s something to be gained from hearing out the person they disagree with,” Cohn said. “It’s dangerous not only for the practice of critical-thinking skills but also for our democratic society. We live in a society based around the clash of ideas and the proving and disproving of ideas that allow us to reach optimal conclusions.”

A speaker silenced — or put on pause?

The flap at Friends began early last week, when school administrators told Atshan — who’d been invited by the school’s Peace and Equality in Palestine club to speak on Friday — not to come. Scores of students, irked by what they saw as censorship, responded by walking out of a weekly, school-wide worship meeting Wednesday and protesting during a dodgeball assembly Friday by holding up signs with slogans like “Let him speak!”

Then, on Monday, teachers Ariel Eure and Layla Helwa, who escorted students during the Wednesday walkout, were indefinitely suspended. The teachers’ school email accounts were disabled, and the locks on their classroom doors, changed.

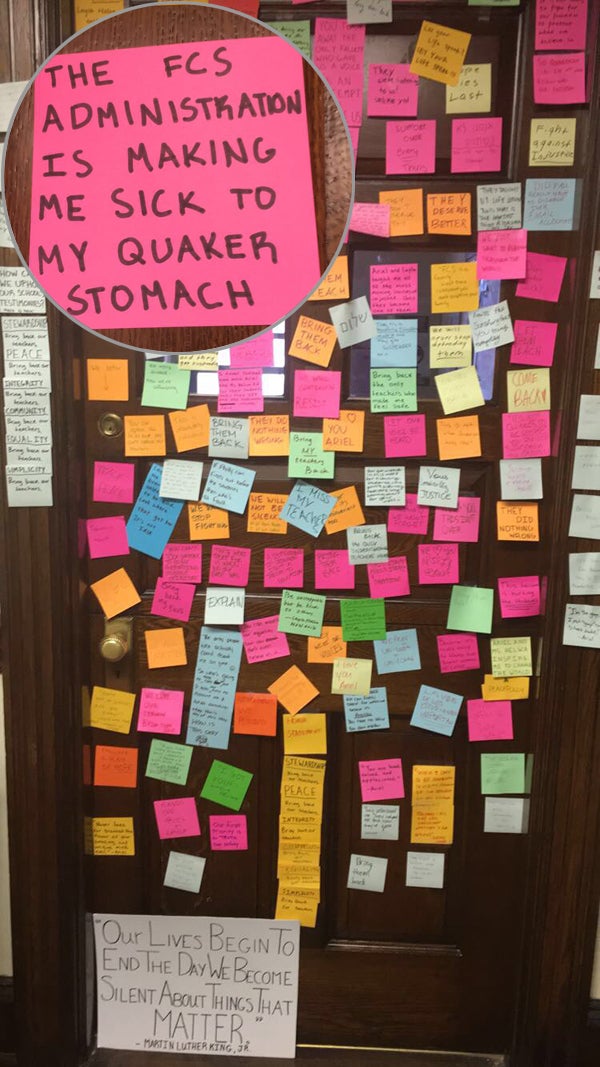

Within hours, the doors became shrines where students vented their frustrations in Post-It notes with messages like “I miss my teachers” and “They did nothing wrong.”

As word of Atshan’s rescinded invitation and the teachers’ suspensions reached the broader community, the school found itself targeted on social media by alumni, parents, and other critics.

“I am disgusted that the Trump mentality has taken over FCS,” one wrote.

Another fumed: “You are no longer practicing true Quaker beliefs but have allowed prejudice and hate to overcome your good sense!”

Sammy Dweck, a 2007 graduate who now works as a real estate broker in Washington, D.C., said he won’t give any more money to his alma mater until they “take action to foster this discussion.”

“I have the greatest respect for my alma mater; it was a wonderful place for me,” Dweck said. “But I take issue with shutting down a discussion that is an opportunity for students to learn, even if the point of view is contrary to that of what are probably some large donors. As a Jewish alum, I believe the Jewish-Palestinian conflict is something of interest to the student body. The administration should be trying to foster a balanced discussion so that students have the opportunity to enact the Quaker value of building consensus.”

Craig Sellers, the head of the school, tried to defuse the mounting fury by posting a statement to the school’s website Tuesday saying administrators merely meant to “pause — not cancel — any speaker engagement on this issue.”

But attorney Mark D. Schwartz, who represents the disciplined teachers, said administrators had previously approved Atshan’s appearance — but canceled it a few hours after it was publicly announced.

“They’re catering to people who write checks,” said Schwartz, whose two children graduated from the school.

Schwartz has filed a harassment complaint with the school’s board of trustees, complaining that Sellers, by disciplining the teachers, violated school discrimination policies.

School administrators deserve every bit of scorn they’re facing, Schwartz added.

“They acted like stormtroopers instead of Quakers,” he said. “We’re in an atmosphere now where educational institutions, which are supposed to be about dialogue, aren’t. “[Atshan] is an academic. He’s not a bomb-thrower. He’s like the pied piper — kids love him. This is perverse. It’s not how you treat faculty members.”

Atshan has declined media requests for comment.

Sellers, meanwhile, announced that the school is creating a task force “to determine how we move forward … and embrace the challenges of intellectual discourse with respect and empathy.”

Such sentiment held little comfort for students, though.

“The school really isn’t telling us anything,” said a student who asked that her name and even her year be withheld because she feared getting in trouble with the school. “We have to find out everything from other news sources. I don’t want to keep protesting against my school. I’ve been here awhile, and I’ve learned so much here. But there are clearly many issues that are not being addressed.”

A hot potato for Quakers

There are few festering political debates as polarizing as the Israel-Palestinian conflict.

That’s probably why speakers from Breitbart editor Milo Yiannapoulos to activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali to scholar Norman Finkelstein repeatedly draw protests when they are invited to speak somewhere. In fact, FIRE found that nearly a quarter of all speaker challenges on college campuses since 2000 stemmed from the speaker’s views on Islam or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

To Jacob Bender, that’s because some Jews regard any repudiation of Israel’s actions in the Middle East as hate speech.

“Even before this new [Trump] administration took over, there was a long history by supporters of Israel to equate criticism of Israeli policies with anti-Semitism. That’s unfortunate and wrong-headed, because many Palestinian speakers have been silenced,” said Bender, who heads the Council on American-Islamic Relations of Philadelphia.

The issue is particularly piquant at Quaker schools, where many students are Jewish. Many Quaker communities support the BDS movement, and the American Friends Service Committee has called for economic sanctions to coerce Israel to end its occupation of Palestinian territories in the West Bank.

Still, FIRE found that speaker challenges are just as likely to come from the left as the right. “It cuts both ways,” Cohn said.

Bender and Cohn agreed that no matter the motive of the speech-squasher, canceling speeches is a wrong approach.

“I understand the feeling of vulnerability of American Jews regarding this issue, but the solution is certainly not censorship and forbidding speakers to come onto campus,” said Bender, who’s Jewish and has a child who attends a local Friends school. “The solution to bad speech is more speech. Schools have to be a place where even unpopular ideas are expressed.”

Cohn added: “I worry that these kinds of disputes are teaching kids the wrong lessons. Will they matriculate to college and say: ‘Well, this [censorship] worked in high school. Let’s do that here.”

Instead, Cohn said, students should especially listen to speakers whose viewpoints they revile.

“Go and listen. Take notes. Stand up and refute the speaker in that setting. Invite op-eds to the student newspaper,” he said, offering ways students and schools can respond to unwelcome viewpoints, instead of canceling speeches. “We have to do a better job of educating students on the philosophical underpinnings of free speech and the value of hearing people you disagree with … Students benefit from hearing ideas they disagree with and learning how to grapple with them and respond to them rather than sticking their fingers in their ears and pretending they don’t exist.”

Mary Catherine Roper is deputy legal director for the ACLU of Pennsylvania, which protects free speech in public spaces. While her group frequently fights free-speech issues in public schools, private schools set their own agendas for how much debate will happen and what ideas get presented to students, Roper said.

Don’t like it? Enroll elsewhere, she suggested.

“In public spaces and schools, we don’t allow the veto of ideas,” Roper said. “In private schools, you vote with your tuition dollars.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.