Amtrak engineer Brandon Bostian found not guilty in 2015 deadly train derailment

The jury has found former Amtrak engineer Brandon Bostian not guilty on all charges resulting from his role in a deadly 2015 train derailment.

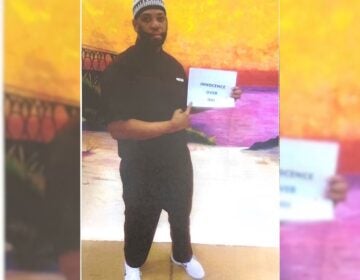

File photo: Brandon Bostian, the former Amtrak engineer involved in a 2015 derailment in Philadelphia that killed eight people and injured more than 200. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

The jury has found former Amtrak engineer Brandon Bostian not guilty on all charges resulting from his role in a deadly 2015 train derailment.

The eight women and four men deliberated for less than 90 minutes before coming to their verdict Friday afternoon. Earlier in the day, the jury panel had to start deliberations over, after one juror dropped out due to a death in the family.

Bostian’s acquittal is the most recent chapter in a long saga to assign blame for what happened when Amtrak 188 jumped the rails near Frankford Junction, just after 9:20 p.m. on May 12. Eight people died, and 185 were rushed to the hospital.

Bostian, the sole engineer onboard, had accelerated his train to 106 mph just before entering the curve and braking, when the speed limit for that stretch of track was 50 mph.

Outside of the courthouse, he became emotional, but let his attorneys speak for him.

“We’ve said from the beginning that this was a terrible accident,” said defense counsel Brian McMonagle. “A couple hundred people were forever changed by it, and a good man has been living the ordeal of being asked to pay for a crime he didn’t commit,” he continued.

The Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office, which prosecuted the case, issued a statement, saying it respected the jury’s verdict. “Our goal throughout this long legal process was to seek justice for each and every victim,” it reads.

Attorney Tom Kline, who represented some of the victims and families of those who died, said having the case go to trial at all was part of the healing process.

“There was an admission … that Mr. Bostian caused a terrible tragedy. And that gives some measure of, I believe, comfort and closure to the families,” he said. Kline said he did not expect the case to be appealed.

A long road to trial

Prior to the 2021 criminal case, federal and local investigators had pored over the incident, which was one of the worst train derailments in U.S. history

The National Transportation Safety Board determined in a 2016 report that “the most likely reason” Bostian failed to slow down is that he thought he was just beyond the curve, where the speed limit increases to 110 mph.

He lost his “situational awareness” because he was distracted by radio reports of rocks or bullets hitting nearby trains, the report continued. The NTSB also found physical changes such as an automatic braking system called positive train control, and stronger windows on passenger cars, could have saved lives or averted the disaster completely.

Amtrak admitted fault, and paid out $265 million to victims and their families.

The courts long debated whether Bostian should face a jury. Special Agent Brian Julien testified that the federal government declined to bring charges against Bostian.

Former Philadelphia District Attorney Seth Williams also passed on the case, saying “we cannot conclude that the evidence rises to the high level necessary to charge the engineer or anyone else with a criminal offense.”

The Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office took up a private complaint filed on behalf of victim’s and their families, and in 2020, the Pennsylvania Superior Court ruled that the case could go to trial.

Judge Barbara McDermott ruled that the jury could only hear evidence that speaks to Bostian’s “state of mind” at the time of the incident. They were not permitted to hear information about Amtrak’s liability, and technology installed after that could have prevented the derailment.

Witnesses for the prosecution testified to the destruction the derailment caused.

The business class car looked like “a can that was ripped open from the middle,” testified Philadelphia Police Officer Craig Perry.

The derailment crushed passenger Blair Berman’s heel bone, and broke her elbow. When she came to after the accident, “I tried standing up and I collapsed,” she told jurors. She testified that she did physical therapy every day for two years as a result of her injuries.

Senior deputy attorney general Christopher Phillips also called several witnesses to show that Bostian’s training, and experience, meant he should have kept his train on the track.

Rock-throwing incidents are common and train engineers must memorize the speed changes and visual landmarks along their route in order to be certified, testified Keith Strobel, who trains locomotive engineers. The two trains actually struck by objects that night, SEPTA 769 and Acela 2173, did not derail.

“Despite knowing where he was, Frankford Curve, he accelerated for 33 seconds,” Phillips told the jury during closing arguments.

Defense attorneys Brian McMonagle and Robert Goggins argued that Bostian was only “human.”

“Do engineers sometimes make mistakes?” they asked Jonathan Hines, Assistant Superintendent of Terminal Operations at Amtrak.

“Yes,” said Hines.

The defense argued that the rock-throwing incidents that night were “unusual,” as were the lengthy radio broadcasts about whether or not the engineer of SEPTA 769 needed medical attention.

“Situational awareness is learned,” said Wilbur E. Wolf III, who testified as an expert witness for the defense. Amtrak was negligent in not better preparing its engineers for how to maintain it, he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.