‘Bored this whole school year’: Philly students reflect on 11 months online

Philly high school students have settled into a school year on track to be held entirely online. Meeting up after class IRL is out. Making new friends via IG is in.

Listen 5:21

Charity Robbins is a 10th grade student at Carver High School of Engineering and Science in North Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the current surge?

Eleven months.

That’s how long it has been since students enrolled in the School District of Philadelphia have stepped into a classroom, chatted face-to-face with a teacher after the bell rings or gossiped with friends by the lockers.

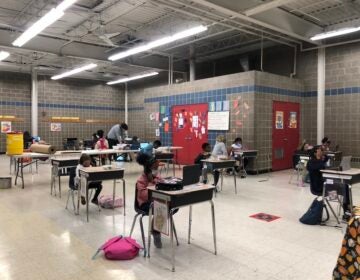

For some young children, that’s set to change soon. District officials announced a plan last week to bring some K-2 students back to class twice a week, starting in late-February.

It’s the district’s third attempt to reopen schools since the pandemic hit last March. The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers opposes any return to the classroom until all members that are required to be in school buildings are fully vaccinated, which city officials have said isn’t likely to occur for months.

For older students, however, there isn’t a tentative timetable to leave virtual learning behind.

“We want to see how [bringing younger students back] will go first,” Superintendent William Hite said in late January.

For Philly high school students, that’s meant settling into a school year that may be held entirely online. Meeting up after class IRL is out. Making new friends via IG is in.

WHYY spoke to students across the city about how they have come to terms with a high school experience no one could have predicted, one that nearly a year later has become all too strangely normal.

New friends on Instagram

Charity Robbins’ smile would light up every class she attends — if the 10th grader ever turned on her laptop camera.

Robbins transferred to Carver High School of Engineering and Science in North Philadelphia at the beginning of the year. She’s yet to set foot in a classroom. The norm in her virtual classes, she said, is for students to be faceless blank squares.

“It’s been so long and I’ve never met any of my teachers,” she said. “And I only know one [student] that I’ve actually met in person … everyone else I know from Zoom.”

She has been able to make a few new friends though, thanks to a group project in journalism class, and a little prodding from her teacher.

“We were forced to work together, right? And at first I was like, ‘Oh my goodness this is going to be weird,” she said. “[Eventually] the teacher goes … you might want to exchange Instagrams.”

Before the pandemic, Robbins worked hard to keep her screen time down. Now, in addition to taking class on her laptop, she said she’s up to about eight hours a day on her phone — mostly on Facetime and Instagram.

“I tried [setting restrictions on Instagram] and I just can’t do it because I don’t know how I’ll get through the day,” she said.

Robbins lives in an apartment in Frankford with her mom and her six-year-old sister. Her mother works at an Amazon distribution center during the day, meaning Robbins has to juggle her classes with keeping an eye on her sibling, who’s been doing first grade virtually through a charter school.

“It’s a little difficult, but I feel like I’ve figured out how to balance,” she said.

Robbins is excited to get to know her new school and new classmates in person whenever they do go back. But she worries that those interactions will be afflicted with what many high schoolers fear most: awkwardness.

“I think it’s going to be a difficult transition,” Robbins said. Because you’re like, ‘Hey, I was the person behind that box that didn’t have the camera on. This is how I look now!’”

An outdoor kid stuck inside

The best part of Maxine Antinucci’s school day used to be when she was deep in the forest, wrist-deep in the loamy soil.

Antinucci is a senior at W. B. Saul High School of Agricultural Sciences. Until last March she would spend much of her classroom time roaming the school’s 130-acre campus, which borders Wissahickon Valley Park.

“During the time of the spotted lantern flies we would go out there and kill them, and actually take some back to the classroom to feed our bearded dragon,” Antinucci said. “I really miss the animals.”

These days, Antinucci is learning about environmental science from behind a computer screen in her bedroom.

Her teachers make the best of it, she said, but it’s not the same.

“We make a podcast and videos,” she said. “I Iike it — it’s fun, but we are supposed to be in the paths and stuff.”

Antinucci, an honor student, has been able to keep her grades up, but her motivation is flagging. Besides the outdoors she misses running track, environmental club, and going to Wawa after school with friends — some of the intangibles that give senior year its luster.

“I wanted to finish with a big bang,” said Antinucci, who’s worked with WHYY’s student reporting labs.

Antinucci shares a house in Roxborough with her mom, and three roommates. The house can get a little cramped, she said, something that wears on her after previously spending so much time outdoors.

One thing is getting Antinucci through this year: her plan to attend Northampton Community College in the Lehigh Valley next year.

The school’s environmental sciences program is appealing, she said, but lately she’s been more excited about two other aspects of enrolling there. Northampton is the rare community college to offer dorm living to its students, and, for now, at least, the school is offering classes in-person.

“I will never complain about walking to school when it rains. I won’t complain about it being cold,” she said. “I won’t complain about school at all anymore.”

When COVID-19 hits at school and at home

Sanai Allen misses her classroom, but is in no rush to return.

A junior at Saul HS, she knows just how dangerous the pandemic can be. Her father died from COVID-19 in January after a month-long illness.

“I miss school so much,” she said. “But I know like, in these times, it’s really not safe to go back. Anybody could catch it.”

Sanai Allen’s dad, Anthony Allen, worked the late shift doing maintenance at Einstein Medical Center.

Sanai said her father’s schedule meant that since school went remote, they were able to find new quality time during the day. He helped her with English class and they joked and traded insights about their love for stock car racing.

“My dad was actually my best friend,” Sanai said. “We basically did everything together.”

These days, Sanai is staying at her brother’s house. She’s found that helping watch two young children is a way to fill some of the space created by her father’s death.

And despite her loss and her added obligations, Sanai has stayed committed to school. She’s laser-focused on being accepted at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University.

The school is attractive for two reasons: it’s a historically Black university, and it’s near where her father grew up and still has family.

“He’s not here with me physically,” she said, “but I know he’ll always be here by my side watching over me.”

Struggling with boredom

Sometimes, when Ghida Abbas has trouble concentrating, the 10th grader at Paul Robeson High School starts daydreaming about a little game she liked to play with her close friend Nabria Jackson before the pandemic.

It involved ice chips and the school nurse.

“I eat a lot of ice so during art class I go [to the nurse’s office] and get ice,” Abbas said. “And if she says, ‘No.’ I ask Nabria to go get it.”

“This is true,” the fellow sophomore said, giggling.

Abbas and Jackson light up when they talk about little moments like this. Meeting at Dunkin Donuts before school, chatting with friends in the auditorium before class starts — the spontaneous moments of connection that make high school days memorable.

It all seems so much sweeter to the two friends now that it’s gone.

“I’ve been bored this whole school year,” Abbas said.

Casual conversation, Nabria added, just doesn’t flow on a Zoom meeting.

“If somebody don’t mute, then you can’t talk,” she said. “That happens a lot.”

Another loss to the virtual learning era: the ability to flirt. It’s hard to be suave when your whole class can watch your every move.

“I’ve seen [a student try and make a move on a Zoom call] before,” Jackson said. “The teacher was like, ‘Stop it.’”

Still, Jackson and Abbas said they’ve gotten used to living through the screen.

At this point, Abbas said, she’s written this year off entirely as a wash.

“I want to end the year online,” she said. “I want to go back next year, so it can be a fresh start.”

Missing the field

For KeShan Allen, the transition to remote learning last spring was tough. But the decision by state health officials to shut down all gyms in Pennsylvania at the same time hit him much, much harder.

The Parkway Center City senior has been lifting weights four days a week since freshman year.

“Mentally, I wasn’t in the [right] mindset,” he said. “[Going to the gym] wakes me up.”

Allen says his mental health has improved since his gym reopened in June. Now, weekdays follow a strict schedule: wake up by 5:30 a.m. to be able to walk to the gym, lift, and then be home and showered before his first Zoom class at 9 a.m.

KeShan conditions for a purpose: He plays defensive back for South Philly High, a football team that fields a squad of students from a number of city high schools.

But it’s been more than a year since Allen and his teammates have been able to take to the gridiron together. Last August, city officials postponed fall sports seasons through the end of January.

The loss hit Allen hard. “I miss Friday night games, getting pumped for those,” he said. “I miss the brotherhood.”

Training is currently scheduled to start up again in March, but a surge in coronavirus cases could cause officials to cancel the season altogether.

Allen really hopes that doesn’t happen. His grades have been flagging a bit, he said, and he’s counting on one last football season to help provide some meaning and unity to the end of his high school career.

“It’s more than a game to us. This is our lives. Especially growing up in Philadelphia, with poverty and violence — sports is a way to stay focused,” he said. “Especially with school being virtual, people are losing motivation. We really need a season.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)