Blazing back-to-school temperatures pose public health threat to students

Only about a quarter of Philadelphia public schools have air conditioning.

Students are released from George A. McCall School at noon Thursday because of the heat. It was the fifth early dismissal for heat for the Philadelphia School District since the school year began. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

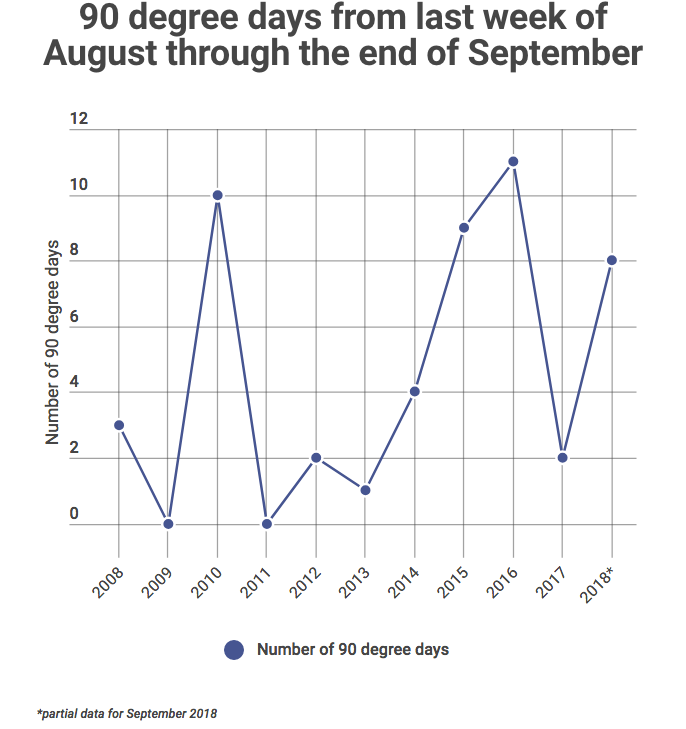

In 2008, Philadelphia recorded three days with temperatures above 90 degrees between the last week of August and the end of September.

A decade later, there have already been eight 90-degree days, and September isn’t even halfway through. And because of climate change, scientists expect more sweltering days in years to come.

Those blazing temperatures have forced Philadelphia schools to close early five times in the two weeks since school began. Only about a quarter of Philadelphia public schools have air conditioning.

Philadelphia’s schools aren’t alone. Other school districts, including Camden City and Shamong Township in New Jersey, have also sent students home early due to the excessive heat.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said Dr. Walter Tsou, the executive director of Philadelphia Physicians for Social Responsibility. “Kids get dehydrated. They actually don’t have the ability to drink enough water perhaps to replenish the supplies.

“Most young people don’t have the sufferings that senior citizens have where they lose their ability to sweat, but it is still a problem. They become lethargic, and they become inattentive under these hot conditions.”

Temperature data for that “back-to-school” period over the past decade has zigzaged up and down. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Philadelphia recorded no 90-degree days in 2009. In 2010, the city recorded 10. And 2016 had the highest number of all: 11.

But the peaks and valleys show a pattern: up, up, up.

“There is clearly a strong trend over the past couple of decades of higher average temperatures across the globe,” said Jerry Fagliano, chairman of the department of environmental and occupational health at Drexel University. “We see that locally as well.”

Fagliano said the city has experienced more frequent extreme heat days and more heat records — and because of climate change, that is likely to continue.

“We need to adapt to the expected rising number of hot days and the extension of heat seasons into time periods that we aren’t typically adjusted to,” he said. “The Philadelphia schools, or any institution, will need to be able to create conditions that children will be able to thrive in.”

Translation: Philadelphia and other school districts will need to air condition their schools.

Tsou agreed, calling the rising temperatures a public health threat. He said closing schools makes sense in the short term, but ultimately that isn’t a solution, especially as temperatures rise.

“Clearly the real long-term solution is we have to put air conditioners in the schools,” he said. “On hot days like this, frankly, there’s no substitute to air conditioning if you want kids to learn.”

Doing so will come at a price. Philadelphia Councilwoman Helen Gym’s office has estimated it would cost $4 million to install wall-mounted air-conditioning units in all Philadelphia classrooms. And even then, the city’s infrastructure may not support the additional draw on the electrical grid.

Still, Tsou and other health experts said the upgrades are essential for the well-being of students and faculty.

“In other areas like Chicago and Europe, we’ve seen thousands of people really who have died from overwhelming heat waves,” he said. “The fact that we’re at Labor Day and we have 94-degree weather outside should disturb us. This is a serious problem.”

This story has been updated to clarify the connection between more days of extreme heat and climate change.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.