Ben Franklin Parkway celebrates its 100th birthday with its own street party

Philadelphia's iconic thoroughfare marks its 100th anniversary with cake, favors, and music.

Listen 2:18

Night skyline of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. (Big Stock photo)

In 1683, William Penn laid out a “greene country towne” with a carpenter’s square: a rigid grid of modestly sized farming plots broken up by symmetrically placed public squares. Philadelphia developed slowly, hugging the ports on the Delaware River and creeping westward toward the Schuylkill.

It would be almost 200 years before the last of Penn’s quadrants – the northwest Logan Square – would be developed. By then, Philadelphia was no longer green, country, or a town. It was a throbbing, burning, choking industrial metropolis.

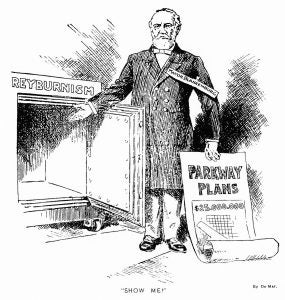

The Fairmount Parkway – later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Parkway – was designed to both correct and affirm Penn’s vision.

“No city can be beautiful when it is laid out wholly on the right angle principle,” wrote the Parkway Association in its 1902 proposal to the city. “Sharp corners are ugly.”

The Parkway was envisioned to be an aberration of Penn’s stern grid, cutting diagonally from the heart of the city – City Hall – directly to Fairmount Park, the largest urban green space in the world.

That tethering of city life to country life was put into moralistic language that a Quaker-like Penn would surely appreciate.

“The evils of modern society have, to a considerable extent, their root in the undue growth of cities and in the estrangement of rural environments,” the proposal read. “One of the remedies may be found in bringing the handiwork of God nearer to man-built piles of brick and stone.”

The Parkway is exactly one mile long, from City Hall to the steps of the Art Museum. It was a massive municipal undertaking that involved seizing and razing about 1,600 buildings, most of them factories.

The Logan Square area had developed as an industry hub. The Baldwin Locomotive Works alone occupied eight blocks for its work manufacturing railroad cars.

But in the first decade of the 20th century, Baldwin had started shifting production to the outskirts of the city, away from the dense urban core.

“It had been built with an infrastructure that was quickly becoming obsolete,” said David Brownlee, author of “Building the City Beautiful,” about the history of Philadelphia and the City Beautiful movement. “Industry was on its way out. The vision was that Philadelphia could remake itself – with important economic and social benefits – by reconceiving itself not as a city of industry but as a city of culture and commerce.”

“We talk about living in a post-industrial city today,” he continued. “Philadelphia was already planning to be a post-industrial city back in the first decade of the 20th century.”

For Philadelphia to be a modern city, the vision went, the Parkway had to be more than a functional avenue toward greener pastures. It had to look good. It had to feel good. Taking cues directly from the grand avenues of Paris and Versailles, it had to inspire.

The original proposal — a big ask to spend a mountain of public money to displace thousands of people and businesses — was based on aesthetics, fresh air, and pleasure.

“It’s talking about beauty, and about people being able to use this Parkway. People who can’t afford to go to Fairmount Park will have the park come to them,” said Laura Stroffolino of the Free Library of Philadelphia who co-curated an exhibition about the evolution of the Parkway, “Corridor of Culture.”

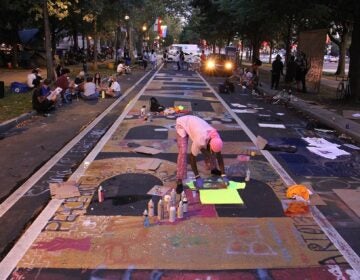

Straffolino juxtaposed excerpts from the 1902 Parkway proposal with photos of how the Parkway has been used over the last century: celebrations and memorials, parades and protests. The same Parkway that welcomed revelry (Live 8, Made In America) and reverence (two papal Masses) has also served as a place to feed the homeless and give sanctuary for nesting hawks.

“Such a plan as this would at once help us to realize the unity of our civic life,” read the 1902 proposal. “Above all things, Philadelphians need such a realization and the inspiring influences that spring from it at the present time.”

A soiree this evening, from 5 to 10 p.m., for the 100th anniversary hopes to draw out the diversity of the city with hundreds of activities along Parkway mile. Every cultural institution will be open late.

The Barnes Foundation, Moore College, and Philadelphia Museum of Art will each have art-making workshops. Food trucks and musicians will roam the street. Every block of the mile will offer some kind of music or performance. The library will host a modern ballet performance, followed by social tango dancing; it will also have an indoor beer garden.

Just as the city celebrates the last 100 years of the Parkway, it is making plans to change it. There is a growing consensus that the boulevard does not serve the residents as well as it should, with its relentless traffic congestion, dangerous crosswalks, and at times awkward fencing for temporary, privately ticketed events.

Conversations have started on how to make the Parkway behave like a park, less like a highway.

Ideally, said Brownlee, the Parkway will never stop changing.

“As we change it, we should be respectful and take advantage of its very good bones, of the extraordinary visual power it has,” he said. “That milelong view from City Hall to the Art Museum is one of the great — it really is, seriously, one of the great human achievements of the 20th century.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.