Before Rosa Parks: The fight for Philly transit equity and the Black women on the frontlines

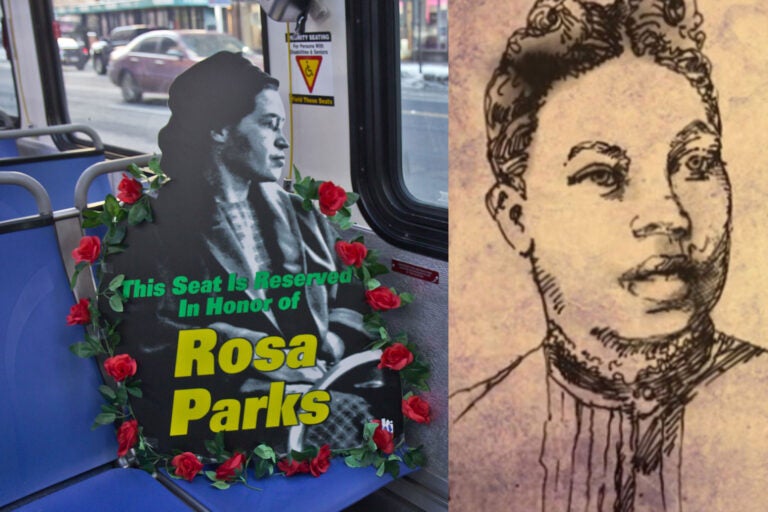

As SEPTA honored Rosa Parks on her birthday, history remembers Caroline LeCount, who risked her life to desegregate 19th century Philadelphia’s streetcars.

Left: Rosa Parks honored during SEPTA ceremony (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY) Right: Caroline LeCount (Courtesy of Transportationhistory.org)

A specially decorated bus sat parked in front of SEPTA headquarters, with a cutout of civil rights hero Rosa Parks on a front seat inside.

The display is a Black History Month celebration honoring her refusal to give up her seat to a white man in the Jim Crow South that led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a major moment in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

“This is just the first of many events and activities and discussions that we will have this month,” said SEPTA General Manager Leslie Richards. “I think it is fabulous that we [are] starting off with an event that honors an outstanding woman and also involves a bus.”

But long before SEPTA’s buses traversed the city streets, mandated to serve riders regardless of their background, Philadelphia had its own civil rights struggle that played out on public transportation. And Black women asserted themselves on the frontlines.

‘No matter how well-dressed or how well-behaved’

Caroline LeCount was a prominent leader in Philadelphia’s Black community in the late 1800s and early 1900s. She was the first Black woman in the Philadelphia area to pass the city’s teacher exam, a supporter of the Union during the Civil War, and an activist who fought to desegregate Philadelphia’s streetcars.

During LeCount’s lifetime, Philadelphia streetcars refused equal service to Black riders. According to research from Philip Foner, a former professor of history at Lincoln University, “of the city’s nineteen streetcar and suburban railroad companies, eleven refused to admit Negroes to their cars.” The other eight “reluctantly allowed them to ride but forced them to stand on the front platform with the driver, even when the cars were half empty, and though it was raining or snowing.” In many parts of Philadelphia, Black people seeking transportation had to walk or hire an expensive carriage.

For LeCount, and Black people throughout the city, the policy was another reminder of a strong anti-Black caste system and presented a significant challenge to getting around the city.

Though Philadelphia was a hotbed for the abolitionist movement, and was even a stop on the Underground Railroad, throughout the mid-19th century, it was a powder keg of racial tensions between white residents, Irish immigrants looking to assimilate into whiteness, and Black residents.

In one of his monthly publications, Frederick Douglass, who himself escaped slavery and became a renowned speaker and abolitionist, determined in 1862 “there is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than in Philadelphia.”

Douglass described an apartheid-like environment — even within the abolitionist movement — with stiff boundaries that upheld white supremacy throughout the city, including on public transportation.

“Colored persons — no matter how well-dressed or how well-behaved, ladies or gentlemen, rich or poor — are not even permitted to ride on any of the many railways through that Christian city,” Douglass wrote.

Those who defied the anti-Black rider policy could face violent removal. But during the Civil War, as Black men enlisted to put their lives on the line for the Union, patience for such treatment among Black residents waned.

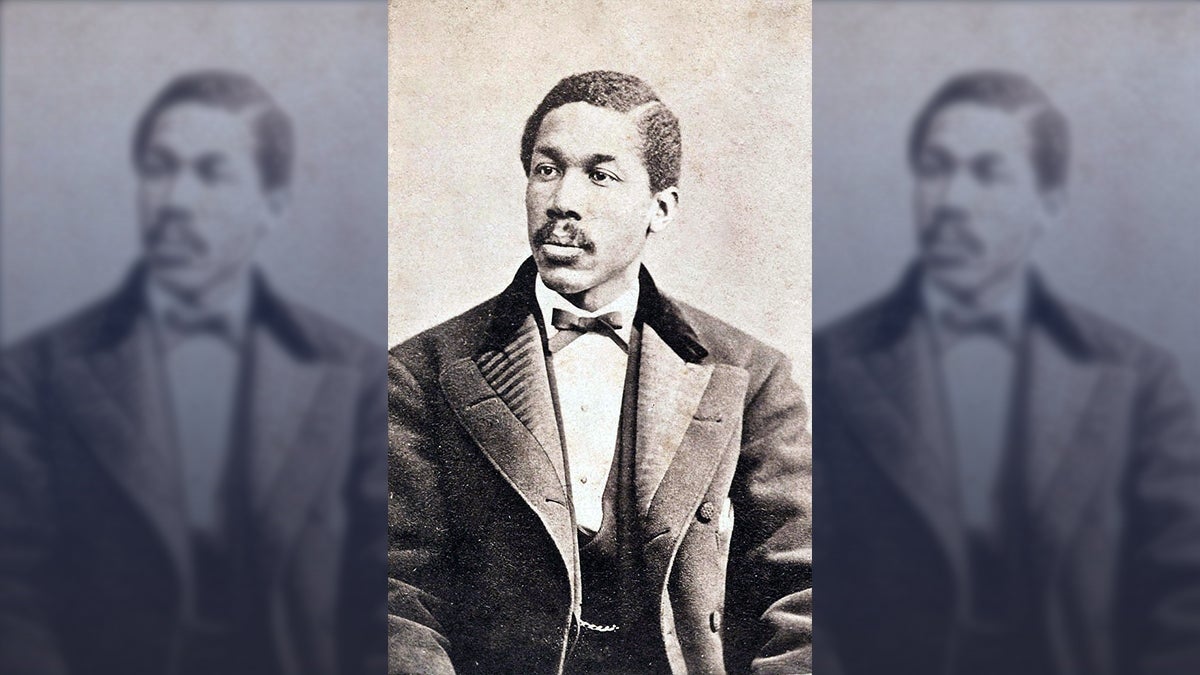

Black activists responded with plans to desegregate the streetcars. LeCount and her lover Octavius Catto, a well-respected activist and educator, also, were among those who strategized for an end to the policy, a Villanova University Library exhibit explains. Catto pursued the legislative route and urged state lawmakers to outlaw segregation on the streetcars. Meanwhile, LeCount and other women chose civil disobedience by boarding streetcars despite the risk of harm.

LeCount and her comrades sustained injuries for their defiance, but they took their cases to court and sometimes won. The cases also helped raise public awareness of the violence, garnering sympathy from some white riders who disapproved of the brutality.

With great violence

It is unclear when exactly LeCount began demonstrating, but there was another woman who may have made such civil disobedience a viable option.

In his article Whiteness, Freedom, and Technology: The Racial Struggle over Philadelphia’s Streetcars, 1859—1867, historian Geoff Zylstra wrote about an elderly Black woman in 1865 named Derry. She had “just finished a late shift caring for wounded Union soldiers in a church building” and wanted to avoid the dark streets. She decided to ride a streetcar, disregarding the racist rule that prohibited her doing so.

After some time, the conductor demanded Derry leave, but she refused. Shortly after that, Zylstra explains, the conductor arranged for his friends to board the vehicle and they ejected her with “great violence.”

Derry sued the conductor and won. The judge in that case awarded her $50. According to Zylstra, the victory sent a message that made it difficult for conductors to enforce the segregation policy.

For example, that same year, “a colored man got into a Pine-street passenger car, and refused all entreaties to leave the car, where his presence appeared to be not desired,” The New York Times reported. The conductor, “fearful of being fined for ejecting him, as was done by the Judges of one of our courts in a similar case, ran the car off the track, detached the horses, and left the colored man to occupy the car all by himself.” He spent the night in the car, according to the paper.

“Her case is seminal because there’s a shift in the strategy of protest after she wins,” said Zylstra, an associate professor of history at the New York City College of Technology. “I think the conductors have to respond as well, because if they start throwing Black passengers off the car, if they hurt them, if they rip their clothing, then they could be legally liable. And her case sort of set the groundwork for that.”

Catto and his colleagues eventually prevailed with lawmakers in Harrisburg. Governor John Geary signed a law prohibiting segregation on the streetcars on March 22, 1867. Still, the work was not done.

Just days after the law was signed, LeCount tried to board a streetcar in the city, but was refused by the white conductor. After the incident, she alerted the authorities and showed proof of the new law. The conductor was arrested and fined $100, sending a message that segregation on streetcars was now illegal.

SEPTA officials said there are no plans to celebrate any of the activists from the streetcar desegregation movement as they did for Parks, but Philadelphia Transit Equity Day coalition hosts an event that also honors Catto. Zakia Elliott, an organizer for the event, said this year’s event will be virtual.

Regardless, Elliott, program manager for Philadelphia Climate Works, said the work of the streetcar desegregation movement continues today and goes beyond transportation.

“Racial justice and transit justice, they’re all tied up together,” said Elliott. “Transit issues are an environmental justice issue.”

A racial hierarchy that continues today

The segregation of streetcars represents an explicit version of how racial hierarchy played out in public spaces. Though this type of overt segregation has been outlawed, Mimi Sheller, director of the Center for Mobilities Research and Policy at Drexel University, said racism still impacts public transportation.

SEPTA’s Regional Rail service, for example, is associated with whiter, wealthier riders, who are able to pay higher fares, traveling from suburbs that were once white-only, while city transit is associated with poorer, Blacker city riders, from neighborhoods that suffered from race-based disinvestment.

“The geography of the city has already been structured so deeply by racial segregation,” said Sheller, professor of sociology and head of the department at Drexel. “So that when you have a transportation system like Regional Rail that goes only to certain suburban areas and costs more money to ride, it’s basically going to create de facto segregation without them having to have an explicit policy.”

Just last week, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission advanced a fare equity and restructure analysis of Regional Rail. The $100,000 study is set to move forward in July once officials secure funds from the U.S. Department of Transportation, and be conducted in partnership with SEPTA.

Outside of SEPTA headquarters at 1234 Market Street, in front of the decorated bus, speaking to an audience and news cameras, authority general manager Leslie Richards pledged her commitment to change for a better transportation system.

“As a SEPTA leader, it is my role to effect change in our organization, because it ultimately affects the communities that we serve,” said Richards.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.