As reports of illegal dumping rise, can Philly bring new solutions to this old problem?

It’s Saturday morning and a group of volunteers is gathered around a vacant lot next to the train tracks at Erie Avenue in Tioga. There’s trash piled everywhere: tires, abandoned pieces of furniture and appliances, and plastic bags hanging from branches.

Raymond Gant, a 60-year-old North Philadelphia resident and founder of The Ray of Hope Project, hands out push brooms, rakes, shovels and big paper bags.

“I want you to cover the whole area,” Gant told them with a military tone. “We want to make sure we get all this trash.”

Gant founded his organization in 2002 after spending some time in prison. Its original mission was to rehabilitate dangerous neighborhoods by helping residents with home repairs while giving jobs to former inmates. But he soon realized that trash was a bigger problem.

“Illegal dumping, litter… You got old chairs and mountains of trash that people unloaded here,” Gant said pointing in all directions. “You got people that come from outside the neighborhood that think this is just a dumping ground. They come and dump their trash whenever they feel like.”

Short dumping is an enduring problem in Philadelphia. An analysis of illegal dumping by Keep Pennsylvania Beautiful found it’s not a problem specific to Philly; it happens in every county. But according to city data, the number of reported incidents and violations issued has been growing for the last two years.

Ray of Hope has been doing neighborhood cleanups at least twice a week for 15 years, Gant says, in partnership with the city’s Community Life Improvement Programs (CLIP). He remembers that back in the 1960s the city would come by and sweep up the neighborhood, bringing water trucks and picking up the trash.

“But all of those services are not available anymore, they are minimized now because of budget cuts and staff like that” Gant said.

According to the report by Keep Pennsylvania Beautiful, people are most likely to dump illegally when there’s a lack of acceptable disposal or recycling outlets, when they can’t pay to do it legally or it represents a savings opportunity, when active dump sites already exist, and when doing it doesn’t represent a risk or a penalty.

Gerald Gregory, 60, is a block captain on the 3200 block of North 25th Street, and a longtime volunteer for Ray of Hope. He said illegal dumping is a big problem in his neighborhood.

“We need enforcement; that’s where the problem is, you have rules but you don’t enforce them,” Gregory said while cleaning. “And we really, really need trash cans. Do you see any trash can anywhere in your eyesight? There’s no trash cans.”

“People are getting more and more upset about it”

Kelly O’Day, a retired environmental engineer, has taken up Philadelphia’s street trash analysis as a personal crusade. He spent 40 years in wastewater management, and trash, he says, is a gigantic water pollution problem.

Philadelphians place about 15,000 illegal dumping and 6,500 vacant lot cleanup service requests through Philly311 every year, by phone or online. O’Day used this data to start mapping trash-related data and found that 6 of the 11 top service codes used by Philly311 to track requests relate in some way to trash. In 2016, 21 percent of the total 181,600 field service requests had to do with trash.

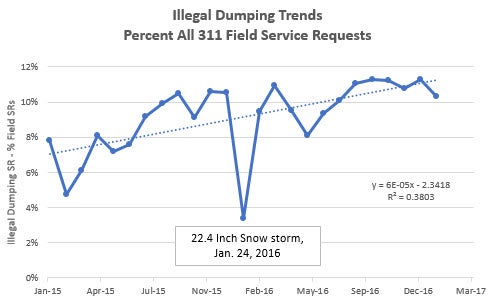

According to O’Day’s analysis, illegal dumping reports have been on the rise for the last two years. There were 55 percent more requests in January 2017 than January 2016, which was already 35 percent more than January 2015.

“I suspect people are getting more and more upset about it,” O’Day said. “But also, there’s more people with smartphones.”

Even as the total volume of Philly311 service requests has increased since January 2015, O’Day calculated that the illegal dumping ones are also increasing as percentage of all requests.

The reports don’t distinguish what kind of trash is found, but some include photos. O’Day manually downloaded all the ones for this past January (302) and mapped them by type, location, and frequency.

Through his observation he calculated that 36 percent of illegal dumping registered was residential trash or bagged trash, followed by tires and construction debris (12% each), mattresses (10%), “mix of trash types” (9%) and TV sets (7%). Most of the trash was dumped on sidewalks (66%), followed by vacant lots and buildings (15%). Judging from the photos, only 5 percent of the locations seemed to be chronic dump sites.

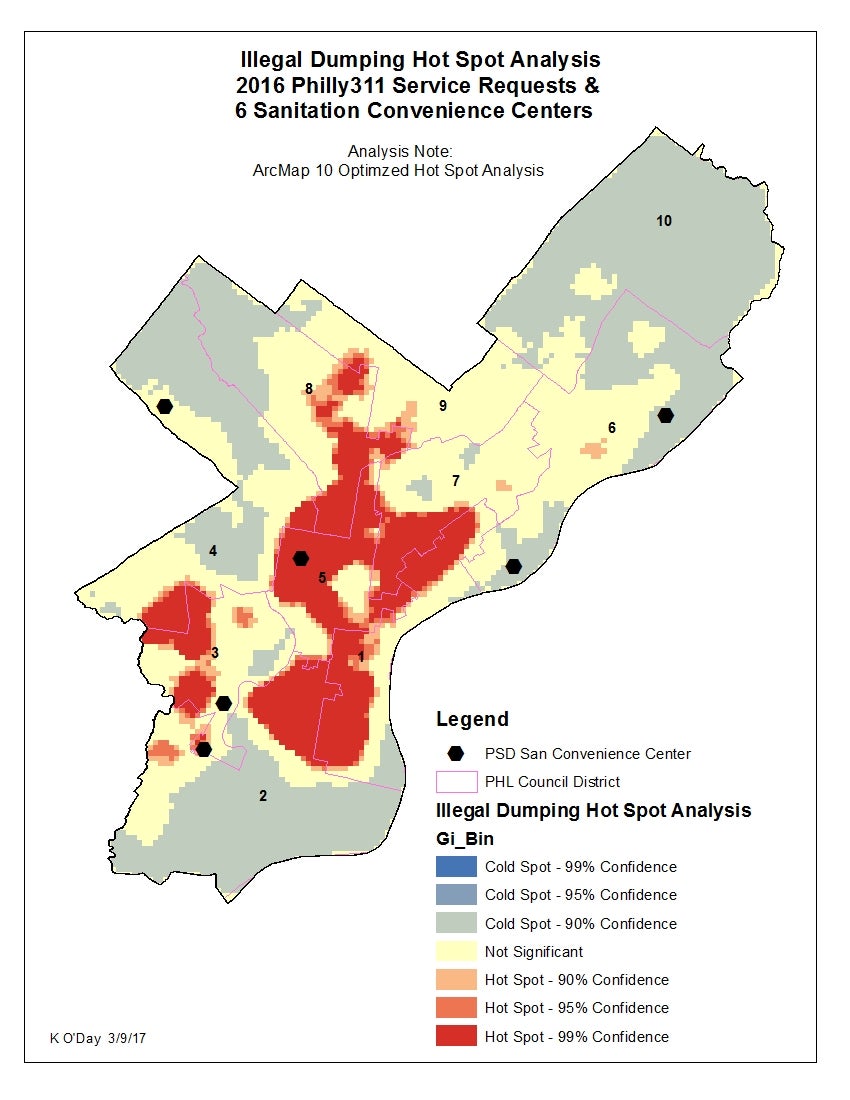

He also used the locations of 2016’s 17,384 illegal dumping service requests to create a map of illegal dumping hot spots.

Earlier this year, Nic Esposito, the Mayor’s Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet’s director, announced the pilot of a digital litter index, which would help the 16-member cabinet produce a comprehensive, data-driven action plan to divert waste from landfills and incinerators 90 percent by 2035.

That was music to O’Day’s ears. The litter index would be better than Philly311 data to understand the scope of Philly’s litter and illegal dumping because it’s more precise and it wouldn’t only rely on residents to submit reports. And although the Street Department already has its own litter index, this version will be digital and the data will be collected by more city departments.

“I think for the first time many departments are trying to figure out what to do,” O’Day said. “They don’t have the answers yet, but at least they’re working together now. In the past, each department said ‘not my responsibility’.”

“People just come to my neighborhood and dump trash. It’s a culture”

Illegal dumping is a big problem in Eastwick, a neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia with abundance of vacant land where people dump construction debris, trash bags, mattresses, and tires. Last week environmental activist and Eastwick resident Joanne Graham told Philadelphia’s City Council the vacant Pepper Middle School has become a magnet for illegal dumping. At one point last year resident Leonard Stewart said he found 600 tires near his home on 86th Street.

“I’m talking about major trash,” Stewart said. “People just come to my neighborhood and dump trash. It’s a culture, I’ve been here 17 years and this has always been the problem. And there’s no enforcement down here.”

Illegal dumping is considered a minor criminal offense in Pennsylvania, with multiple penalties and enforcing agencies. In 2016, the Philadelphia Police Department issued 468 summary offenses for short dumping citywide, more than 100 more citations than the previous year, mostly related to household trash, followed by construction debris.

Philadelphia Code also regulates short dumping. Notices of violation, issued by police officers or other authorized inspectors (Streets Department, CLIP and Department of Licenses & Inspections) are not criminal offenses, but the offender receives a citation and must pay a fine.

The number of violations issued by CLIP for illegal dumpers in vacant lots has also been increasing, from 29 in 2015, to 65 in 2016, and 93 so far this year. CLIP inspectors say 70 to 80 percent of the violations are issued to construction companies and 20 to 30 are for household trash.

But Stewart, like many other sources interviewed for this story, thinks current enforcement mechanisms are not effective enough. He personally takes photos and reports short dumping to the police at least twice a week (and instructs his neighbors to do the same), but as soon as the trash is removed, someone dumps again. He also patrols his neighborhood during the day, but he says most of the dumping happens at night. Two years ago, he said, CLIP installed cameras in the neighborhood, but people were still dumping.

“You need more enforcement and higher penalties,” Stewart said. “If they know they’re getting fines, they’ll stop. But right now, they know it’s open season.”

Meir Badush, owner of EZ CleanUp LLC in South Philly, picks up trash from houses and construction sites and takes it to dump yards where he pays around $90 per ton. Doing the right thing, he said, “is not difficult at all; you just got to pay.” But he thinks that people don’t really understand that they need to pay for trash to be removed.

“You don’t need special skills, you just need a truck and go. Why would I pay to the dump if I can just dump it over there and save the money? They got nothing to lose. You only get fines if you get caught, but they don’t.”

Russell Zerbo, from the Clean Air Council, has been following illegal dumping and other pollution-related complaints mainly in Eastwick and Kensington for a couple of years. He says enforcement is limited because most of the time police or sanitation officers need evidence: a name, an address or a license plate.

“So you have attempts of enforcement, but they’re not solving the problem of anonymous dumping,” Zerbo said. “You can only write a ticket if you know who are you writing the ticket to.”

Both illegal dumping and enforcement come at a high public cost, according to the Keep PA Beautiful report. Investigating illegal dumping crimes is time consuming and labor intensive for state and local governments, and each illegal dump site costs $600 per ton, for an average of $3,000, to remediate. Honest residents end up paying more to subsidize the loss of revenue from those who do not pay and dispose of waste illegally.

“Definitely doable, but challenging”

When Councilwoman Cindy Bass announced a trash task force for the 8th District, she called illegal dumping an epidemic, and named four contributing factors to the problem: “inadequate trash collection, construction and commercial dumping, lack of information on the city’s sanitation convenience centers, and the reduction in trash receptacles citywide.”

Kelly O’Day, who is part of the task force, believes that most of the residential dumping happens because people don’t have storage space for trash and they don’t want to keep it in their homes for a whole week.

“Ultimately we have a capacity problem,” said O’Day. “We generate trash 24 hours a day, but we only have collection once a week.”

Philadelphia Streets Department does weekly residential curbside trash and recycle collection. The city also has six sanitation convenience centers, open 10 hours a day, 6 days a week, where residents can dispose of bulk items, tires (limited to four a day), e-waste, mattresses and more, for free. But many residents don’t have the means to carry their trash to a center, and as O’Day noticed, only one is located in an area he identified as a hot spot for illegal dumping.

The lack of trash cans is also identified by many as a problem. Curbside trash receptacles can become a magnet for residential trash dumping and to prevent that, they have sometimes been removed. The city has also been replacing wire trash cans with BigBelly solar-powered trash compactors with more capacity. But “the root cause of the receptacle dumping is inadequate trash collection services,” he said.

“They [the city] could have a trash can on every corner. That’s one way to do it [fix the problem],” Clean Air Council’s Zerbo said.

Although Keep Philadelphia Beautiful’s Michelle Feldman knows that solving Philadelphia’s illegal dumping problem means conquering several huge challenges, she’s optimistic. Mostly because the zero waste cabinet, which she’s part of, presents a new approach.

“This is a hard problem that has been around for as long as anyone can remember, whether you’re talking about street litter or illegal dumping,” said Feldman. “But I do think having all of the voices in one room will be very powerful. The city is building the capacity, which is exciting, and we see a commitment.”

Like the causes of illegal dumping, the solutions should vary for every neighborhood, Feldman said. And that’s why the data from the new litter index will be crucial to inform their decisions and to design tailored strategies through enforcement, outreach and education.

“It’s doable, definitely doable. But challenging,” Feldman said. “We’ve seen over the years that Philly makes positive changes: Our single stream recycling program is incredibly successful in so many ways, this is the 10th year of the Philly Spring Cleanup with more and more projects collecting fewer bags of trash, and more people are doing beautification.”

Esposito said the zero waste cabinet has been talking a lot about enforcement, trash bins, collection, convenience centers, street sweeping, and ways to reduce waste. A behavior committee is also trying to figure out how to create the cultural change needed to solve the issue, and the new litter index is being piloted to create a baseline.

But the problem won’t be solved overnight, he said.

“We’re tasked with being able to wisely spend tax money and create resources for over 1.5 million people,” Esposito said. “If we’re going to do that, we want to make sure that we’re looking at it from every angle possible.”

Even though people like Eastwick’s Leonard Stewart or North Philadelphia’s Ray Gant are tired of illegal dumping, they keep fighting because they know it’s important for their communities.

“Do I get tired? Oh yes, I’m exhausted. I’m burned down, I’m whipped,” said Gant, after a cleanup. “This is important to our community and to our kids coming the next generation. They see this every day, why ain’t nobody talking about this? They’re walking on top of trash, they don’t have places to go play, it’s sad.”

Deion Morrison has been volunteering with Ray of Hope and working with ex-offenders for more than 15 years. “I don’t agree with people calling this city Filthadelphia,” Morrison said while looking volunteers put an old piece of furniture into the truck. “No, I don’t agree with it, because I take ownership. If I do my part then I can’t say this is a filthy city, I just don’t believe it, I don’t believe it. There’s always room for improvement.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.