As Philadelphia works to tackle climate change, a question emerges: Is PGW on board?

The city-owned gas utility has discussed with industry groups a Pa. Senate bill that would prevent Philly from taking steps to promote electrification.

Listen 6:08

Former Philadelphia Gas Works offices on Broad Street in South Philadelphia (Nathaniel Hamilton for WHYY)

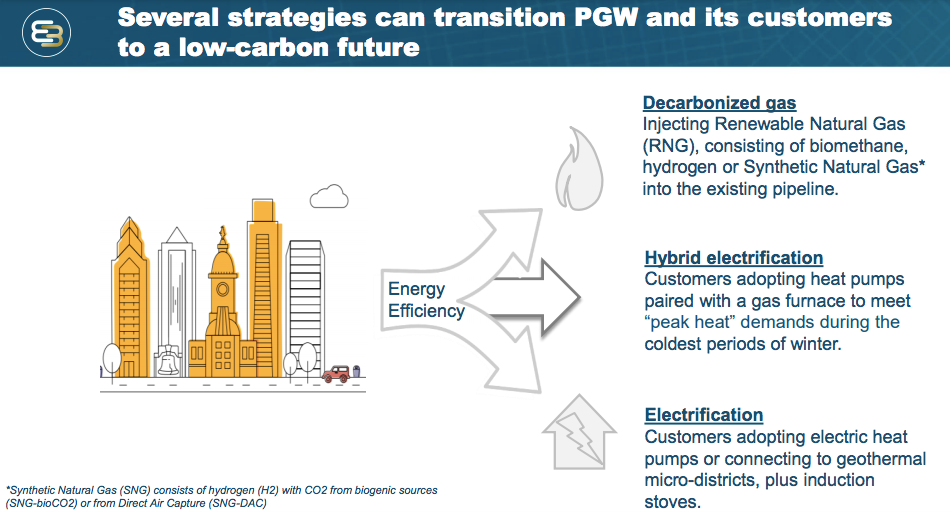

Julie Greenberg, a climate and racial justice advocate who works with the interfaith grassroots group POWER, has a vision for Philadelphia’s energy future: GeoMicroDistricts, or a network of underground pipes carrying water, shared by homes in a single block or neighborhood, powered by the region’s abundant geothermal energy. High-density polyethylene distribution lines would transport water, instead of gas, to heat pumps inside the homes, providing heat in the winter and air conditioning in the summer.

Gone would be the natural gas that now flows through about 6,000 miles of pipes across the city, many as old as a century. And gone with the gas would be one of the city’s largest sources of the greenhouse gas emissions that are heating up the planet. A pilot project is now underway in Massachusetts, and Greenberg said it fits POWER’s four tenets for moving away from fossil fuels — affordability, renewability, fair labor, and health and safety.

“We don’t want affordable energy that destroys our ability to live on the planet,” she said. “We don’t want renewable energy that no one can afford. We don’t want the workforce abandoned. And we can’t have the pipes explode during the just transition.”

But that vision is up against a powerful force in the city. Philadelphia Gas Works — the largest publicly owned gas utility in the country — has a role in utility trade organizations that are working against efforts to transform fossil fuel providers. Documents and emails obtained by WHYY News raise questions about the part PGW’s vice president for regulatory and legislative affairs, Gregory Stunder, plays in an effort to strategize around legislation that would block municipalities from limiting fossil fuel use and promoting electrification — potentially undermining the city’s own climate goals and the officials and elected representatives tasked with coming up with solutions, including members of City Council, the city’s Office of Sustainability, and even the Philadelphia Gas Commission, which approves PGW’s budget.

PGW says it has no position on such legislation recently introduced in Pennsylvania.

On May 11, the same day the Philadelphia Gas Commission, led by City Councilmember Derek Green, held a town hall on a report detailing options for PGW to move away from simply providing fossil fuels, Pennsylvania lawmakers in Harrisburg conducted a hearing on a bill that, if passed, could tie the city’s and the Gas Commission’s hands on that very effort.

Greenberg testified at the town hall, championing a future that transitions away from burning fossil fuels and toward electrification while maintaining good paying jobs and affordable energy bills. For her, the geothermal pilot projects taking place now in Massachusetts tick all those boxes. A similar effort here would give Philadelphia a chance to nip away at its carbon emissions and reach its goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. It would create lots of jobs, would be safer than natural gas, and, she believes, at scale it could be affordable.

Buildings, from giant skyscrapers to tiny rowhouses, are the source of about one-third of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. So cutting climate emissions includes focusing on home appliances, how efficient they are and how they are powered. But even as advocates and city officials move to update building codes to make them more efficient, PGW has opposed such efforts.

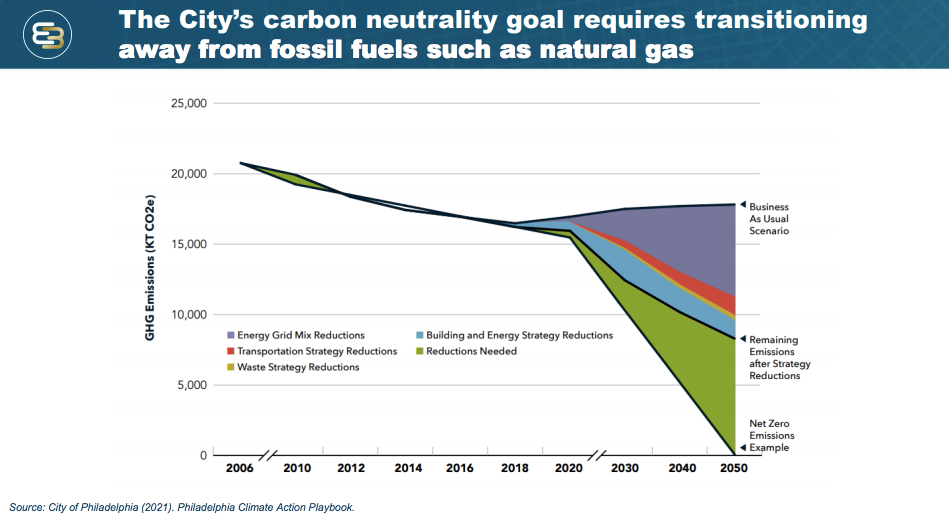

Still, the move toward electrification just got more urgent with a report issued by the International Energy Agency, which says governments need to do a number of things to bring carbon dioxide emissions to net zero by 2050, including banning new oil and gas furnaces by 2025. And that presents an existential crisis for utilities such as PGW.

Dueling visions of PGW’s future

One of Philadelphia’s biggest climate conundrums is what to do with PGW, which employs about 1,600 people and, as a public utility, is completely reliant on ratepayers for income. This, in a city where one-third of PGW’s customer base lives in poverty — and where, in some neighborhoods, residents pay a much larger percentage of their income on energy than the national average of 3%, according to Christine Knapp, director of Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability.

Transitioning away from natural gas is a challenge for PGW. The fear is that the most affluent ratepayers will be the first to ditch fossil fuels, leaving a larger and larger percentage of low-income customers who can’t afford to leave, and can’t afford to pay their gas bills. Black and Latino ratepayers in Pennsylvania are more likely to experience shutoffs and pay a higher portion of their income toward utilities than their white counterparts, according to a report released in March by Community Legal Services and the Pennsylvania Utility Law Project.

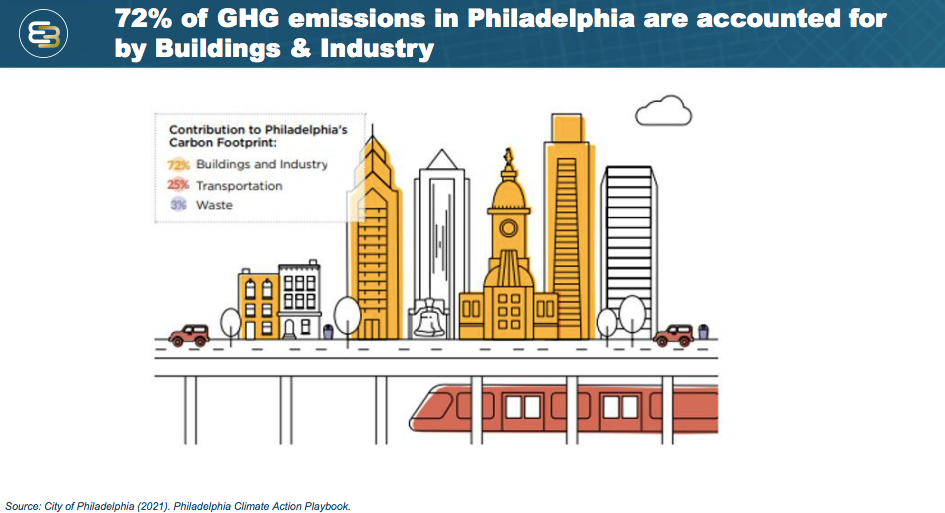

And yet, 72% of Philadelphia’s greenhouse gas emissions come from buildings and industry, much of those dependent on gas service from PGW. The city has a goal of 100% clean energy for municipal buildings by 2030.

Knapp is spearheading a project to examine how PGW could be transformed sustainably. Funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies’ American Cities Climate Challenge, the draft of the PGW Business Diversification plan was discussed at the May 11 town hall and includes the potential GeoMicroDistrict grid pilot that Greenberg and other climate activists are promoting. But Knapp recognizes the complexities of reforming a centuries-old gas utility.

“There’s a problem when we have a carbon neutrality goal and own a fossil fuel utility,” she said.

And there’s an even greater problem if that fossil fuel utility appears to oppose electrification efforts.

A February investigation by NPR shows how trade groups in which PGW maintains membership have been working against efforts by local municipalities to tackle climate change through electrification. The industry has worked with Republican lawmakers in 23 states to introduce “preemption” bills, which it has labeled “energy choice” legislation, that would forbid local governments from enacting measures that would discourage fossil fuel use and encourage electrification.

The push for such preemption bills began when Berkeley, California passed a law in 2019 banning new natural gas hookups in some buildings. Resulting measures restricting towns and cities from following in Berkeley’s footsteps have passed in 10 states, according to Sage Welch of Sunstone Strategies, a public relations firm focused on climate change.

“We think there’s a problem with the fossil fuel industry working with utilities to tell cities what they can and cannot do regarding climate change,” she said.

A Pennsylvania proposal that could tie Philly’s hands

In four states, including Pennsylvania, the legislation is in the early stages, Welch said. State Sen. Gene Yaw, a Republican from Williamsport who chairs the Environmental Resources and Energy Committee, introduced Pennsylvania’s version of the bill earlier this year. Although no municipalities in Pennsylvania are considering bans on new gas hookups, the broad language of Senate Bill 275 has climate activists and local municipalities worried. It forbids towns and cities from restricting “the connection or reconnection of a utility service based upon the type of source of energy to be delivered to an individual customer within the municipality.”

The Energy Association of Pennsylvania, to which PGW pays a yearly membership fee, has advocated for the Senate bill, and its president and CEO, Terrance Fitzpatrick, testified at the May 11 hearing on the legislation.

“We also recognize that there are different views within the U.S. and Pennsylvania on issues concerning the environment and, particularly, how to address climate change,” said Fitzpatrick. “Some believe that all fossil fuels should be ‘kept in the ground’ and that we should immediately stop building infrastructure to transport these forms of energy. In view of these trends, we believe it may be just a matter of time before some municipalities move toward restricting sources of energy.”

Testifying on behalf of the Pennsylvania State Association of Township Supervisors, director of government relations Joseph Gerdes questioned the origins of the legislation, calling the language generic and not crafted specifically for Pennsylvania.

“As such, we are concerned that these terms could be broadly interpreted and could be seen as preempting local land use controls, which we would oppose,” said Gerdes.

The union that represents 1,150 of PGW’s workers testified in favor of the bill, saying electrification efforts would jeopardize those jobs and put an undue burden on low-income ratepayers.

“We are convinced that Senate Bill 275 will serve the dual purpose of helping to ensure the continuity of 1,600 good-paying PGW jobs, jobs with quality health care and retirement benefits that will likely be lost otherwise, while guaranteeing that significant economic costs will not be thrust upon Philadelphia’s poorest citizens,” said Keith Holmes, president of Gas Works Employees Local 868. “There can be no dispute that if the city were to somehow eliminate natural gas as a source of energy, all of these good jobs would be lost and could not be replaced with a viable alternative.”

PGW did not answer questions posed by WHYY News about its yearly fees to industry groups, but its FY 2022 operating budget seeks $127,000 for the Energy Association of Pennsylvania. It also pays yearly dues to the American Gas Association, listed as $445,000 for FY ’22, and is an active member in the American Public Gas Association, for which it has budgeted $58,000 in FY ’22 dues.

Though PGW says it has taken no position on Senate Bill 275, the Energy Association of Pennsylvania has advocated for the bill, and the American Gas Association and the American Public Gas Association have advocated for similar bills nationwide.

In April, Philadelphia City Council passed a resolution opposing SB 275. That resolution was introduced by Councilmember Green, chair of the Philadelphia Gas Commission, one of the three entities that oversee PGW.

“I always have concerns when at the local level we don’t have the flexibility to do all the various types of initiatives that could be beneficial for the citizens of the city of Philadelphia,” said Green.

Like Julie Greenberg, Green is very interested in exploring geothermal microgrids, but he said SB 275 could prevent PGW from pursuing that option.

“Senate Bill 275 would restrict us to just using gas,” Green said. “And that’s something that is not beneficial for the diversification of PGW going forward.” He said he sees a future for PGW, which was originally a lighting company then transitioned to heating homes.

“I see PGW going through another transformation like it did from a lighting to heating company and being more of an energy company,” Green said. “And I think there’s going to be some very good opportunities in [Biden’s infrastructure proposal] for the ability of Philadelphia Gas Works to look at various pilot opportunities. Having a Senate bill that dictates to municipalities like Philadelphia that we can have only one type of energy source … is a disservice for us here in the city of Philadelphia.”

Is PGW undermining the city’s climate efforts?

Just two weeks after passage of that City Council resolution, the Energy Association of Pennsylvania testified in favor of Senate Bill 275 at a hearing and submitted written testimony stating it was speaking on behalf of its member utilities, including PGW. A PGW spokesman said including the agency as supportive of the bill was an “oversight.”

Between early January and early February of this year, more than a dozen emails with multiple attachments about SB 275 were exchanged between upper management at PGW, including vice president of regulatory and legislative affairs Gregory Stunder, and Sen. Yaw’s chief of staff and executive director of the Environmental Resources and Energy Committee Nick Troutman; PGW contract lobbyist in Harrisburg Gmerek Government Relations; PGW outside counsel Daniel Clearfield; and staff from the Energy Association of Pennsylvania, the American Gas Association, and other unnamed utilities. The content of those emails is not revealed because PGW is fighting to keep them from public view.

One email exchange, with the subject “discussing legislative strategy,” included Daniel Lapato, senior director of state affairs with the American Gas Association. The Texas Observer, a nonprofit news organization, along with the climate reporting site Floodlight, recently reported on how Lapato asked for support from a publicly owned gas utility in Tennessee for a similar bill that state lawmakers there approved.

The content of the PGW emails discussing SB 275 is part of ongoing litigation in a Right to Know case brought by Charlie Spatz of the Climate Investigations Center. Spatz has sued to get PGW to release the emails. “It’s critical for Philadelphians to know whether their city-owned utility is at odds with the city’s own climate policies,” he said.

The privilege log that details the records being withheld was obtained by WHYY News. The log includes references to meetings held by the Energy Association of Pennsylvania about Senate Bill 275, legislative strategy, and draft language.

PGW submitted a 26-page brief to Pennsylvania’s Office of Open Records in defense of its right to withhold those emails from public view. As part of that defense, PGW’s Stunder claims, among other things, attorney-client privilege and in an exhibit to the brief describes email exchanges with his outside counsel, Daniel Clearfield, in this way:

“My communications with Mr. Clearfield reflect strategy used to develop or achieve successful adoption of Senate Bill 275 in that they analyze particular language in the bill and similar laws.”

PGW spokesman Richard Barnes told WHYY News that “Gregory Stunder and Mr. Clearfield only discussed the strategy being used by others related to the bill and its potential for passage. PGW has not taken a position on the bill.”

Barnes said that the utility did not hire lobbyists to advocate for SB 275, and that its staff members provided “technical feedback.”

“With respect to Senate Bill 275 in particular, PGW’s staff provided technical feedback in response to various stakeholders who invited review and comment, however we did not employ any lobbyists related to the bill,” Barnes wrote in an email to WHYY News. “We are concerned about the costly impact limiting energy choices would have on our customers’ wallets and the huge economic burden it would place on the finances of the city of Philadelphia. PGW serves an already cost burdened population.”

Barnes said the utility has a “robust sustainability portfolio,” citing goals for reducing methane emissions.

In the brief challenging the Right to Know request, PGW points out that despite its being a public agency, Pennsylvania’s Natural Gas Choice and Compliance Act requires it to be treated as a competitive business, and as such, it is exempt from some aspects of the Right to Know law.

PGW did not answer a list of detailed questions submitted by WHYY News, including its position on whether a city should be able to implement electrification rules, and whether its own staff members lobbied on behalf of the bill. Nor did it answer questions on whether it took steps to promote or communicate support for the bill, or whether it encouraged other groups to do so.

In its filings as part of the Right to Know case, PGW suggests that it fears being sidelined if it is forced to reveal the communications from the trade groups and other utilities, which are not subject to the Right to Know law, and that it wants to protect itself from competition.

“Mr. Spatz is asking the Office of Open Records to expose the written communication records of PGW’s legislative lead tasked with and responsible for developing PGW’s legislative strategy with respect to remaining competitive in the energy market on that very topic. Such exposure, and violation of Section 2212(t), would shut down PGW’s ability to freely strategize and engage in the frank exchange of opinions and ideas regarding energy policy. (Stunder Attestation, ¶¶ 23- 24; Fitzpatrick Affidavit).”

The brief challenging the Right to Know request continues: “This will have devastating results for the public, particularly the residents of the City of Philadelphia who rely on PGW as an affordable and reliable source of energy. Industry partners and others who share a competitive strategy but do not wish to develop energy policy from a fishbowl will ultimately leave PGW out of the conversation, resulting in energy policy and legislation that does not take into account the needs and interests of the gas ratepayers of the City of Philadelphia.”

With regard to “technical feedback,” the state’s lobby disclosure law is unclear, according to attorney Adam Bonin, who advises political candidates on compliance with the statute.

“With ‘technical assistance,’ it’s not explicitly in the law,” said Bonin. “But it’s along the lines of when a legislative or government official is asking you for advice, then you’re not really lobbying them, you’re not making an effort to persuade. That is plausible. That they haven’t hired lobbyists on this doesn’t mean they don’t lobby.”

Both the Energy Association of Pennsylvania and Sen. Yaw have intervened in the public records case on the side of PGW and keeping the emails from public view.

A spokesperson for the Kenney administration said PGW has been given explicit instructions not to lobby for SB 275.

Office of Sustainability Director Christine Knapp said the city has a long history of opposing preemption bills, including the most recent actions by state lawmakers to prohibit plastic-bag bans. She said passage of SB 275 could limit the city’s efforts to reach its climate goals.

“While it is appropriate for PGW to work with affinity groups and answer questions on the impact of any such legislation on PGW, it would be inappropriate for PGW to lobby for passage of a bill that preempts the City’s authority,” Knapp said in an email. “Direction to not conduct such lobbying has been made to PGW management.”

A complex relationship

The Philadelphia Gas Commission approves PGW’s budget. The mayor appoints two members of the commission, two are appointed by City Council, and the fifth member is the city controller. The commission approves both the operating and the capital budgets.

Philadelphia Facilities Management Corp. is a nonprofit contracted by the city to oversee the day-to-day management of PGW. Its members are appointed by the mayor.

Though the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, which approves PGW’s rates, does not allow lobbying expenses to justify rate increases, there is nothing illegal or unusual about lobbying by a utility, even a publicly owned utility.

PGW’s 2021 operating budget includes $505,000 for lobbying and consulting services. So though PGW cannot use lobbying expenses to justify a rate increase, because it is a publicly owned utility ratepayers still end up footing the bill. It’s unclear what exactly those budgeted funds are used for, but PGW spokesman Richard Barnes told WHYY News that they include monitoring and commenting on legislation that could have an impact on customers, particularly costs.

Stunder, PGW’s vice president of regulatory and legislative affairs, is not registered as a lobbyist. According to Pennsylvania law, employees do not need to register if they lobby on behalf of their employers less than 20 hours each quarter.

But Stunder plays an active role in industry groups that are working to pass preemption legislation as well as address safety and cybersecurity issues. He is a member of the American Public Gas Association’s committee known as the Direct Use Task Group (DUTG), and emails obtained by WHYY News show his participation in the long-term strategy group, which has as one of its goals passage of preemption bills, or what the industry calls “energy choice legislation.”

An October 2020 APGA board report details a meeting from January of that year that included an update on the task groups’ study on electrification that claims electrification will not help reduce carbon emissions. “The purpose of this study is to report the costs associated with electrification, with the conclusion that the cost of electrification is not a cost-effective means of reducing carbon emissions from commercial or residential buildings or from transportation.”

The board report also lists “energy choice legislation” as a top priority for the group, with a focus on supporting state efforts to push for the preemption legislation.

“With a priority on energy choice legislation, the DUTG is planning on how to support those in states that are looking to pass energy choice legislation in what looks to be a busy 2021,” reads the board report. “While many 2020 state legislature sessions were, and a few still are, focused on COVID-19 relief efforts, APGA staff expect 2021 sessions will be the next opportunity for legislation in states, in addition to those that have already passed, ‘Balanced Energy Resolutions.’ To date, Arizona, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Louisiana have passed bills protecting consumers’ ability to choose their resources.”

Rob Ballenger is an attorney with Community Legal Services, which has a contract with the Philadelphia Gas Commission to provide oversight when it comes to rate increases. Ballenger acts as a public advocate, doing the tedious work of scouring PGW budgets and balance sheets to figure out whether sought-after rate increases are justified.

In the past, he said, PGW has asked his agency to support its attempts to block efforts to increase the energy efficiency of appliances. But he said PGW did not reach out to him about SB 275. Each year, he said, he asks the Gas Commission to reduce PGW’s lobbying and trade membership expenditures that go toward lobbying, but so far it hasn’t.

“Our main position is that lobbying doesn’t benefit customers,” Ballenger said. “They always trot out that they lobby for [the low-income assistance program] LIHEAP, but I say, ‘What additional dollars have you gotten for LIHEAP?’”

At the May 11 hearing in Harrisburg on SB 275, Clean Air Council attorney Robert Routh spoke against the bill. Routh and other environmental and climate advocates are calling for a public accounting of PGW’s lobbying expenditures.

“There’s clearly a tension there between the goals and intentions of the utility with what the city itself is trying to do,” Routh said. “I think it is worthy of public interest and attention. Ratepayers are paying member dues to the AGA, the APGA and the EAP, and that money is being used to fight against the ability to even consider policies to limit the use of gas in buildings.”

Without the text of the back-and-forth emails regarding the state’s preemption legislation, it’s unclear whether PGW has lobbied in support of SB 275, or whether it has simply given feedback to lawmakers. But Julie Greenberg, from POWER, said PGW’s membership in trade organizations alone is enough to give her pause.

“What we do know is PGW uses ratepayer dollars to belong to trade organizations that are lobbying to undermine the city’s own goals,” Greenberg said. “In April, the city passed this resolution [against SB 275)], and PGW is working against the city’s own democratically chosen direction. This use of operating budget money against the interests of the city is not OK.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.