Artists define what it means to be human in a post-digital age

In the era of Instagram, where digital images are cranked out by the gigabyte, and where multiple selections of any image can be summoned up through Google images, what does it mean to make art?

The Art Gallery at The College of New Jersey addresses this in Image Tech: Making Pictures in a Post-Digital Age through April 24. Six artists challenge the categorization of art objects and the role of the image in a broader cultural context. Indeed, we learn, some artists are craving a return to a tactile relationship with materials, such as the smell of oil paint.

“When we think about making art, a great majority of us still consider the medium of paint or the apparatus of the camera in relationship to artistic production,” said curator Mauro Zamora, assistant professor in TCNJ’s department of art and art history. “The best description for our current age can be defined as post-digital, one in which digital information is as important as its physical manifestation.”

Painting has not evolved all that much since the first cave paintings some 40,000 years ago. Photography ushered in the age of abstraction, and later a return to a flat painting. With digital editing tools, photography has gone from cinematic to painterly, and as Instagram users manipulate images on the screen, it enhances an understanding of the painting process.

More than a decade ago, computer scientist and MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte declared the digital revolution over. In his 2011 book “The Future of Art in a Postdigital Age,” artist and educator Mel Alexenberg suggested new art forms emerging from a post-digital age address “the humanization of digital technologies.”

There’s even a hashtag for it. In 2012, artist Theo-Mass Lexileictous launched his #postdigitalismmanifesto at the P3Studio Gallery in Las Vegas. He envisioned extracting the digital, using computers, printers and scanners, into the physical, creating a hybrid medium. In the art world today, a large number of artists cross over from the analog to the digital, even if it’s just creating a digital file to reproduce, market or archive a work on paper or canvas. It no longer matters whether it’s defined as a painting or a photograph, it’s still pigment on a substrate, said Lucas Blalock, one of the show’s artists.

Rather than get mired in the theory, it makes sense to look at the art. In “Deep Still” by Brooklyn-based artist Trudy Benson, a white canvas appears to have been spray painted with a blue scribble, then layered with pasted-on shapes painted in a way that showcases the brush strokes, and layered again is a kind of calligraphy of thick strands of paint. Benson is “heavily influenced by early digital painter programs such as MacPaint or Windows Paint,” said Zamora. “Her marks are at times frenetic, gyrating the way one might move a mouse through a digital space when learning to use a painter program. Even though Benson’s work has moved away from its early digital influence, her marks still speak to the screen, allowing the viewer to see through the painting to its original untouched layers.”

Blalock, also based in Brooklyn, uses photography as an armature, calling into question the role of the photographer as documenter. “Staple,” an archival inkjet print, is a photograph that looks like a photorealistic painting of the grain of a wood surface—you want to touch it to see if it’s actually printed on wood—splotched with pools of stain, and the embedded scar from where a staple has been removed. In “Sweater (Watermelon Print),” a white wooly puff fills a plastic bag from the dry cleaner’s, printed “Sweater expertly cleaned,” but also hand painted with wedges of seeded watermelon. Blalock is contrasting the levels of creation, from the coarse grain of the fabric against which the bag leans, to the plastic itself and the shadow it casts, with the mysterious white woolen thing, the machine printing on the bag, and the painted-on fruit.

In Amy Sillman’s animated “Pinky’s Rule,” the artist made images on her iPhone in response to poet Charles Bernstein’s words, and the poet, in turn, responds to her animated forms.

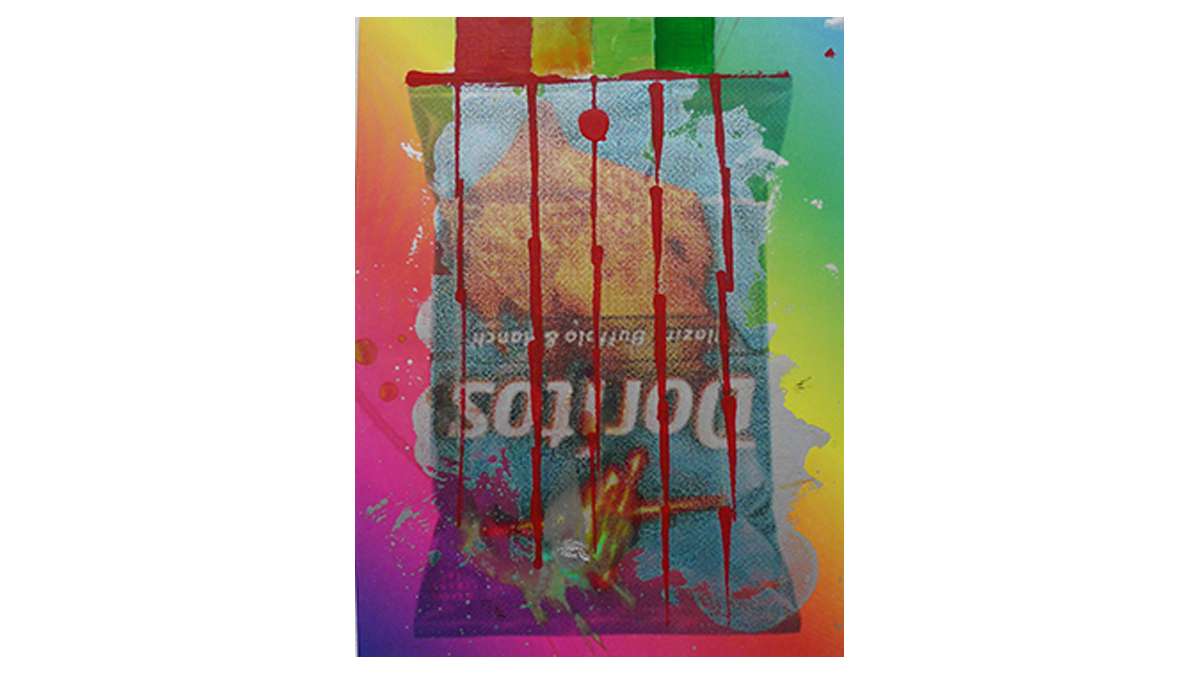

Tom Holmes has printed a bag of Cheetos on a wall-size sheet of aluminum, then desecrated it with paint in the shape of abstracted flowers and paint dribbles.

How can an artist depict the virtual space that surrounds us?

One of the most striking works is Wolfgang Tillman’s “Studio Still Life,” a 5-by-8-foot depiction of a contemporary work station with its tangle of power cords, chargers, keyboards, mouse, laptop and monitors; plants and bookshelves; piles of papers, folders, file cabinets; and the human elements—a wine glass, water bottle, beer bottle, tissues, ashtrays and three packs of cigarettes branded “Smoking kills.” The objects tell the story. On the two monitors we see what might be the inside of a garage and a waiting room, unflattering fluorescence revealing more than we care to see, humans thumbing their devices. It’s quiet here, in the room outside the screens.

It’s a world we’re all too familiar with, the messiness and grittiness of our lives, and yet we search for the humanity. It was only later that I thought to look at the label—it’s an inkjet print—but “Studio Still Life” proves that regardless of media, it’s the impact that makes it art.

____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.