Art of the Caribbean diaspora comes together at PAFA

Two artists — one Haitian, one Cuban — collaborate on "Swarm," an exhibition about the Caribbean diaspora.

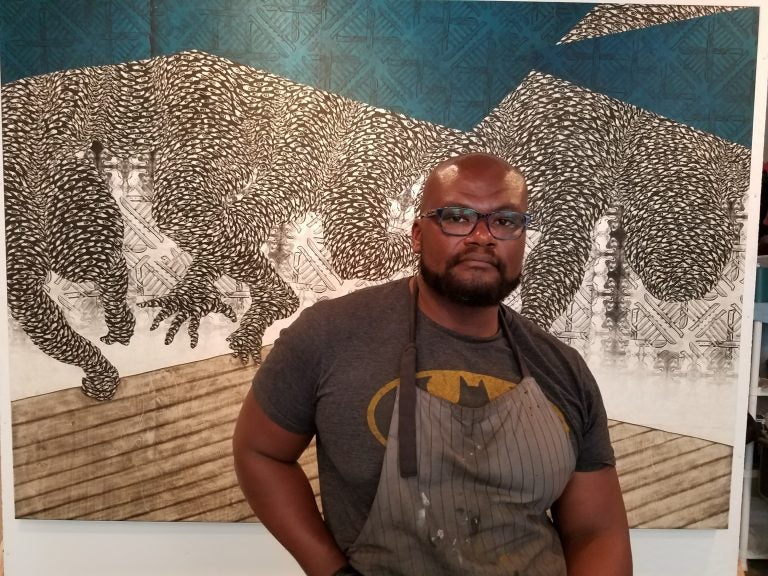

Artist Didier William pauses in his studio at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

An exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia puts together work by two artists, both immigrants from the Caribbean islands.

Didier William, currently PAFA’s MFA chair, was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. At 6 years old, he immigrated with his family to Miami where he spent his adolescence.

Nestor Armando Gil, who teaches at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, is a second-generation Cuban whose family immigrated to northern Florida.

The show, “Swarm,” is an artistic collaboration, a challenge to identity representation, and a call to action for immigrants of the Caribbean diaspora.

William and Gil were a match made by the founding director of Experimental Printmaking Institute at Lafayette, Curlee Raven Holton. In 2016, while leading some of his PAFA students to Lafayette for a visit, William was corralled into Gil’s studio by Holton, who then left the two strangers alone.

“We quickly discovered a lot of conceptual overlaps and thematic overlaps in the work we do,” said Gil. “About 10 minutes later, Curlee came back in, clapped his hands together, and said, ‘So, when are you going to do a collaboration?’ ”

Gil and William spent more than a year talking, visiting, befriending each other, and trading ideas and materials toward the realization of “Swarm.” An early iteration of the exhibit opened in Miami’s Prism gallery late last year. but the PAFA show includes some newer material made since then.

“I don’t think either of us made things for ‘Swarm’ we would not have done otherwise,” said William, whose large-scale paintings on wood panel include featureless black silhouettes covered in hundreds of eyes, laboriously carved into the paint.

“Something exciting happens when you put them together. Regardless of one’s point of origin, there’s a natural impulse to make sense of the world. That impulse is heightened when the idea of home is elsewhere,” he said.

Gil’s work is more sculptural, often using material referencing his Cuban identity — tobacco leaves, spark plugs from mid-century Chevys, inner tubes similar to those used by refugees to float to Florida, and votive candles labeled with Caridad del Cobre (Our Lady of Charity) overseeing Cuban refugees crossing the ocean.

While their artistic approaches are very different, the two artists found common ground as Americans with immigrant backgrounds.

“The common ground is rich with problems. The notion of bringing together people from a lot of places is not supposed to sound like a rainbow coalition,” said Gil. “When Cubans arrived in Miami, they were not made to feel welcome, but they made it happen for themselves. And then — no surprise — Haitians arrived in Miami and received the same treatment by the Cubans as the Cubans received when they arrived.”

Although coming from generally the same part of the world and arriving generally in the same place, Haitians and Cubans in Florida are often treated differently. Many Cuban immigrants arrived as political refugees, while the federal government considered Haitians as economic refugees. As a result, Cubans were often treated more favorably by U.S. immigration authorities.

“In South Florida, you have two populations of people, Haitians and Cubans, neither native to that region but both vying for sociopolitical access and agency,” said William. “The way white supremacy renders that condition into a life-or-death situation for those two populations — those things come to the surface when we bring the work together.”

The title of the show, “Swarm,” is a vaguely threatening call to action. On one level, it’s a gathering of individuals toward a common frame of mind — artists discovering their work echoes nicely off each other. On another level, it’s a vast field of tiny actions that effect a domination.

“This notion of immigration perceived as a ‘swarming’ — the president of the United States recently said that people are ‘infesting,’ ” said Gil. “But, of course, also it’s an imperative or a directive, that one must swarm.”

“What do we do with this this moment, when it seems like every facet of our lives – as immigrants, as people of color, as queer people – is under attack?” said William. “A swarm is nomadic, massive, constantly adapting and shifting. It’s impermanent, but omnipresent.”

Different approaches

As politically strident as the exhibition presents itself, William’s paintings resist explicit interpretation — political or otherwise. They are the result of a career of experimentation and working in a range of techniques, from site-specific wall drawings, to abstract, poured-paint canvases, to printmaking.

The imagery William is currently working with — blank figures covered in eyes — is an act of defiance of the gaze: absorbing the racialized, gendered, sexualized assumptions of viewers and turning it back on them with a hundred unblinking eyes.

To the casual observer there is nothing particularly Haitian, male, or gay about his work.

“I like to trouble it and tease it and provoke it as much as possible,” said William about painting with sociopolitical intention. “At one point in my work, it was more explicit, but that kind of explicit narration is less interesting to me now.”

Gil’s work, on the other hand, tends to be much more explicit. For a performance during the show’s opening reception, he lay on the floor of PAFA’s gallery and had — by turns — sugar, tobacco, coffee, and sand poured into his mouth. That child of Cuban immigrants was smothered to the point of not breathing by those iconic Cuban materials. The performance piece is called “Boca (Your Memories Are My Myths).”

“I try to make things that have a personal narrative and a more macro perspective,” he said. “It’s not a personal journal.”

One of Gil’s wall installations features dozens of spark plugs hanging by fishing hooks. It’s a comment on the iconic Chevys of Havana. It’s also about his father.

“My father was a car guy,” he said. “I grudgingly helped in the garage fixing old cars that became the family cars for all of my young life.”

Gil’s mother also appears in his work, particularly in a set of giant rosary beads made from inner tube rubber. The material of “oración (ave Maria)” refers to Cuban refugees crossing the ocean in inner tubes, while the shape of the work refers to Cuban’s uniquely syncretic practice of Catholicism.

At its root, it comes from the faith of Gil’s mother and grandmother.

“I’m not faithful, but the expressions and poetry of it were most pronounced in these incredibly strong women who raised me,” he said.

Although shy of saying his mother practiced a syncretic form of Catholicism infused with elements of Afro-Cuban Santeria (“you gotta be careful saying that around Catholics”), Gil admitted he is impressed by people who bend religion to fit their own experience of the world.

“I’ve gone to Catholic churches where it’s not Latino, and some where they are, and it’s different, man,” he said. “There’s a different sound when voices rise in song, a different body contact when people shake hands and wish each other peace, the way the priest puts the host directly into your mouth rather than in your hand.”

Although reverent, Gil’s mother was no saint. Another set of his works features tobacco leaves pressed to paper that has been laser-etched with phrases from his elders overheard as a child. The phrase attributed to his mother — unprintable here — is salty.

After its summer run at PAFA, “Swarm” will go to Lafayette College.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.