Amid omicron ‘deluge’, Philly area schools weigh how to move forward

School districts across the region are trying to navigate the current COVID-19 wave, sometimes drawing different conclusions about what's best for students and staff.

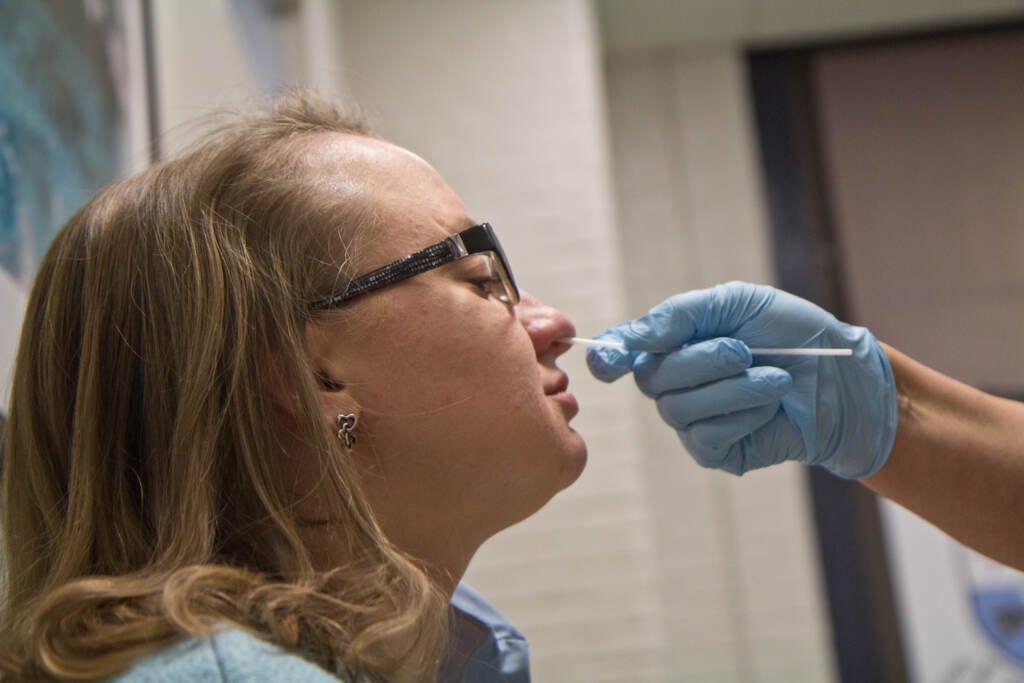

Jill Farina, an Olney Charter High School history teacher, said she was supportive of virtual learning over the holidays for the safety of students, teachers and their families, as she got tested for COVID-19 by Luz Costano, COVID Coordinator, on December 23, 2021. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the coronavirus and vaccines?

On a recent morning, a sixth grade teacher at Drexel Hill Middle School woke up feeling normal. He went in to school, then started developing COVID-19 symptoms. A rapid test confirmed he was positive.

“We had to get him out of the building and we had to, midday, scramble,” recalled Matthew Alloway, the school’s principal.

On a normal day, in a normal school year, it wouldn’t be too hard to find a substitute or get another teacher to cover.

But as COVID-19 cases surge and the omicron variant spreads throughout the Philadelphia region, some schools like Drexel Hill, which is part of the Upper Darby School District, are increasingly under-staffed.

“We have gotten into what I would say is uncharted territory,” Alloway said. “I’ve never been in a situation where I’ve seen this number of people absent, for legitimate reasons.”

On a given day, 15 teachers might be out, Alloway said, with only three or four substitutes to fill the holes.

“That means everybody else who’s healthy has to work through their preparation period [to cover classes],” sometimes pushing themselves to the point of exhaustion.

Everyone was already stretched thin when that sixth grade teacher went home, so Alloway took over one of his classes. He tried to engage students in a lively debate about the material — and ward off endless requests to use the bathroom, the bane of every substitute teacher.

Still, even with the rising case counts and growing absences across Upper Darby schools, the district stayed committed to keeping schools open for in-person learning before winter break.

Barring a dramatic change, they’ll return in person after the new year.

“Right now we’re pushing forward,” said Superintendent Daniel McGarry. “Our plan is to hold our breath, push through, get to the break, and hopefully by mid-January we’ll see some kind of break in this. But I will tell you that if we continue at the pace we’re continuing at right now, my story may change.”

School districts across the region are trying to navigate the current COVID-19 wave, sometimes drawing different conclusions about what’s best for students and staff nearly two years into the pandemic.

Mastery Schools, a charter network with 24 schools in Philadelphia and Camden, shifted to virtual learning on Dec. 23 and will stay remote until Jan. 18.

Nine of its schools had to close the week before winter break, due to the number of positive COVID-19 cases — all crossing the 3% positivity rate the Philadelphia Department of Public Health set as its threshold to pause in-person learning.

Concerns about spiking COVID-19 cases and testing limits led Mastery to move all its schools online, according to Chief Operating Officer Matt Troha.

The government contractor it used to get PCR tests switched to a new vendor and test results have been delayed, he said. Mastery ordered 10,000 rapid tests, for wider-spread testing with immediate results, but they won’t arrive until mid-January.

So, a brief switch back to virtual school is “going to be the best for both teaching and learning and health and safety,” Troha said. “We are hopeful, like everyone else, that this is very short. We can get students back in person very soon so they can get the very best education.”

Navigating the ‘deluge’

The School District of Philadelphia chose a different route, planning to come back in person immediately after the break unless the city health department changes its guidance.

“We remain confident in the fact that we have been practicing very useful mitigation practices, such as handwashing, the use of hand sanitizer, the universal mask mandate that’s in our schools,” said spokesperson Monica Lewis.

“We firmly believe that in-person learning is best for our students,” she said, noting that Philadelphia schools serve as a safety net for many children.

The district plans to stay in close communication with PDPH over the break, “and if they advise us to make changes, we will make those changes.”

On the last day before winter break, 20 of the district’s more than 200 schools were temporarily closed due COVID case rates, according to PDPH.

Omicron “sort of deluged schools [last] week,” said Dr. David Rubin, director of the PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

In schools where CHOP regularly tests students, the number of children with “evidence of infection” has risen from about 1% to 5%.

And while it’s still early to make predictions about how fast the new variant will move through the community, “based on what we’re seeing out of South Africa, there’s [likely] going to be a swift peak here and then recovery’s going to begin,” Rubin said. “The burden of disease will likely be lower in mid-January.”

As long as a region’s hospital capacity hasn’t been exceeded, Rubin said, his group doesn’t recommend virtual schooling: “We’re encouraging schools to push through and open up on time.”

Still, concerns remain about classrooms functioning effectively in the meantime; with so many staff members calling out, operations are under strain.

In Upper Darby, 100 teachers were absent each day, on average, between Dec. 6 and Dec. 20. That’s out of about 950 teachers district-wide.

“This is not to say shame on teachers,” Superintendent McGarry stressed. “The reality is there’s a lot of factors that go into the stress of teaching. People are getting sick. They have their own families. Those numbers that I’m giving you speak to all the pressure that’s on public education right now.”

He noted some staff and students have also called out because of concerns about safety beyond COVID-19, like when threats against schools emerged on TikTok earlier this month.

“There were definitely times when it’s been like, ‘Oh my gosh, we just had six or seven cases where students are positive. Four or five teachers in that building are now positive, and we’re in a lock in” because of behavioral issues, which McGarry attributes to both social media and the stress and toll of the pandemic. “How much more can we take?”

Complicating matters, when staff members are out for COVID-19, they’re kept away from school for an extended period.

“With the COVID protocols, if you test positive, you don’t come back to school as soon as you feel better,” Matthew Alloway, the middle school principal, noted. “You are on a mandated timeline of 10 days. So even if your COVID case just feels like a cold — a little scratchy throat or light fever that clears up after a day or two — you’re still on a timeline where you can’t be back in the school.”

‘Catch-22’

In Philadelphia, COVID-19’s human toll was thrown into stark relief earlier this month, when Alayna Thach, a senior at Olney Charter High School, died of complications from the virus. The source of her infection has not been made public. She was weeks away from an appointment to get vaccinated, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

On the chilly Thursday morning before winter break, teachers at Olney took turns getting COVID tests.

They were teaching virtually. Soon after Thach’s death, teachers called out of school in large numbers in protest, forcing Olney to go remote for a week. Many are calling for increased health and safety measures at the school, which is run by ASPIRA of Pennsylvania.

Nate Decker, a senior English teacher at Olney, sat through a nasal swab — a quick test to make sure he’s healthy before joining family for the holidays.

He’s glad classes temporarily went remote.

“I’d rather have my students safe,” he said. “I’d rather us, the teachers, be safer.”

Decker got to know Thach well last year, through the creative writing club he led, and said she was amazing, enthusiastic, kind, and the type of person genuinely concerned about others’ wellbeing.

While students were remote, “she was always trying to come up with ways to get school spirit high,” Decker said.

Like in an early Zoom meeting, when Thach mentioned how, during a previous virus, schools would set up picnic tables so students could eat in the parking lots or football fields.

“They’d have it spread out so they’re far enough from each other,” Decker recalled Thach saying, suggesting Olney follow suit so everyone could still have lunch together.

“I was like who is this 11th grader just doing research on her spare time on how we can still have a school community while in lockdown? And every meeting she was like that, all the time.”

It’s difficult to mourn Thach and support grieving students right now, Decker said.

“It’s a catch-22 of, in one sense, I want to have a community.” Being around students in person helps him catch how they’re really doing. “It’s easier to get those little intonations.”

At the same time, “when we know that she dies of a deadly disease that spreads quite quickly through interpersonal contact, and especially knowing that Alayna was very conscious of COVID and the dangers and the concerns about COVID,” taking a temporary pause felt, to him, like the right call.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.