Major new art attraction for the work of Alexander Calder opens in Philadelphia on Sunday

The $100 million Calder Gardens, on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, reinvents what a museum is supposed to do.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

If you want to understand the life and work of Alexander Calder, the abstract sculptor popularly known as the inventor of the suspended mobile, the Calder Foundation invites you to explore its website.

But if you want to feel a personal connection to Calder’s buoyant, colorful shapes and enter into a shared space with these fluid objects, the Calder Foundation has built a building for that.

“Go to calder.org and we present so much grad-student level information for people that want to dive down,” said Sandy Rower, grandson of Alexander “Sandy” Calder and president of his foundation.

“We wanted this to be different,” he said at Monday’s ribbon cutting of Calder Gardens. “We really wanted this to be more of a sacred experience, a personal experience instead of using your head.”

Calder Gardens, a center devoted to contemplating and communing with art, opens on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway this Sunday, Sept. 21. It is intended to present artwork closer to the way Calder intended.

“The esthetic value of these objects cannot be arrived at by reasoning,” Calder wrote in a 1933 exhibition catalogue. “Familiarization is necessary.”

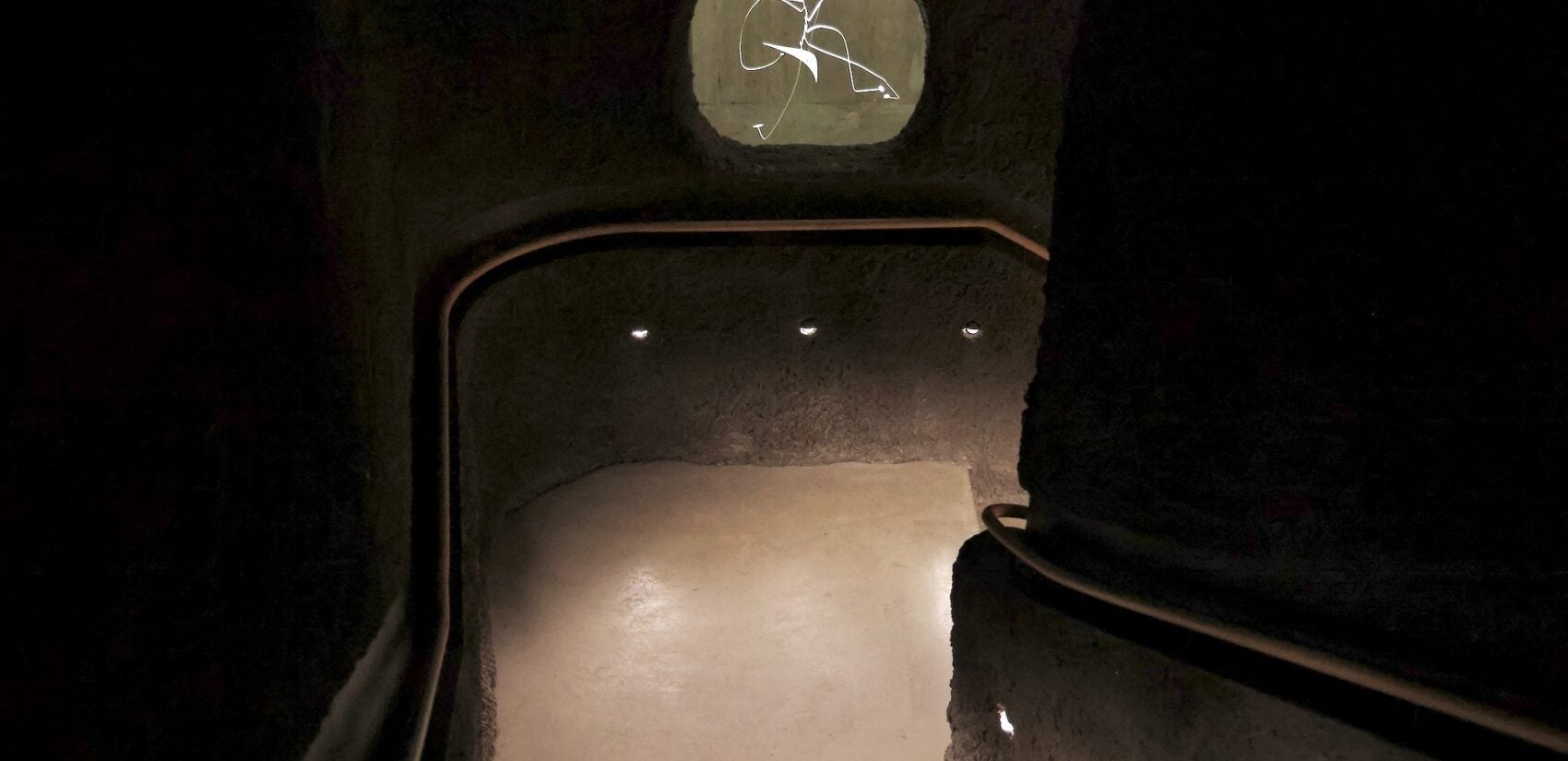

From the Parkway, the pale, wooden building by the celebrated architect Jacques Herzog, of Herzog & de Meuron, resembles a chalet nestled into a meadow, its stainless steel roof gleaming in the sun. That is just the tip of the iceberg. The galleries are underground with large caverns, small niches and winding promenades connecting sunken gardens that peek into the rolling undulations of the surrounding landscape designed by Piet Oudolf.

In a similar way to how Calder rebelled against the classical figurative work of his two famous predecessors — his grandfather Alexander Milne Calder designed the William Penn statue atop Philadelphia City Hall, and his father Alexander Stirling Calder designed Swann Fountain in Logan Square — Calder Gardens rebels against typical museums.

There is no wall text accompanying the Calder sculptures, paintings and works on paper occupying the galleries. There is little to identify or explain what visitors are looking at, which, of course, is intentional. Visitors are encouraged to plumb their own reactions to artwork instead of trying to figure out their place in art history.

“Over the course of the 20th century, North America’s museums have evolved in the direction of education over the kind of direct aesthetic experience that is privileged here at Calder Gardens,” said Thom Collins, president and executive director of the Barnes Foundation, which is administering Calder Gardens in partnership with the Calder Foundation.

Calder Gardens does not call itself a museum, even though to the casual observer it looks like a museum and quacks like a museum. With a tagline, “Open for Interpretation,” the Gardens are a cultural destination for the contemplation of Calder’s work.

What the individual works mean can vary from viewer to viewer. At the opening of the building, Gov. Josh Shapiro offered his own interpretation.

“We gather here today to celebrate the opening of this beautiful museum, but we also gather here today in what is an extremely divisive time in this great nation,” he said. “To me, there are still just a few things out there that allow us to speak a common language. I think sports is one. I think food is another, and I think art is another. We now have an opportunity through the arts to bring more people together.”

Calder Gardens had been more than a decade in the making, with various starts and stops driven, chiefly, by philanthropist Joseph Neubauer. What had started as a $40 million concept on city-owned land escalated to $70 million when construction started in 2022, then ballooned afterward to almost $100 million, according to Neubauer. The commonwealth contributed $20 million to the project.

To make Calder Gardens a contemplative, even meditative, space, the design of the building was critical. The Swiss architect Herzog was asked to imagine environments that would best showcase sculptures, without knowing which sculptures would be curated.

Rower admitted that he gave Herzog very few guidelines from which to start designing.

“To not have a brief — to not walk in the door and say it has to be this tall, it has to be this many square feet, has to be built for this many dollars, all the usual brief stuff — was a very unusual process,” he said.

“I found it interesting that there was literally no brief. But we were speaking. We were creating an atmosphere together that could be that thing,” Herzog said. “I’ve never done what I’ve done in this project, which is tons of sketches and drawings helping me understand what this animal could become.”

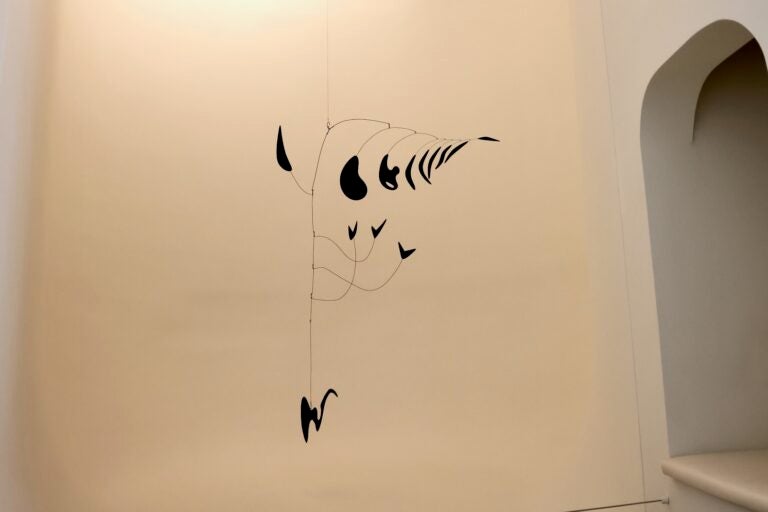

The resulting building is a string of micro-environments visitors pass through, as though exploring a cave. The surface-level lobby is finished in vertical planks of softly pale hemlock. People can either walk down steps that double as bleacher-like auditorium seating, or maneuver down a dark, narrow staircase chute finished in rough, craggy plaster resembling an underground grotto.

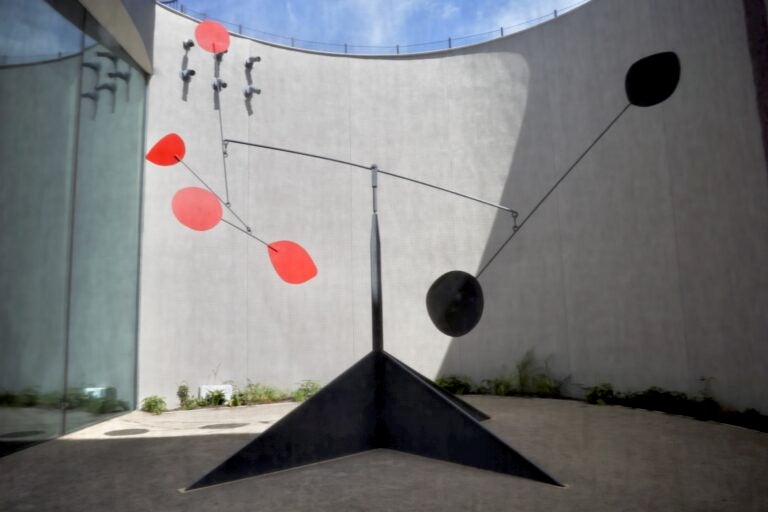

Once at the gallery level, the space dramatically decompresses into expansive, exposed concrete spaces dominated by the enormous “Jerusalem Stabile,” an abstraction of red sheet metal standing 24 feet across and 12 feet high.

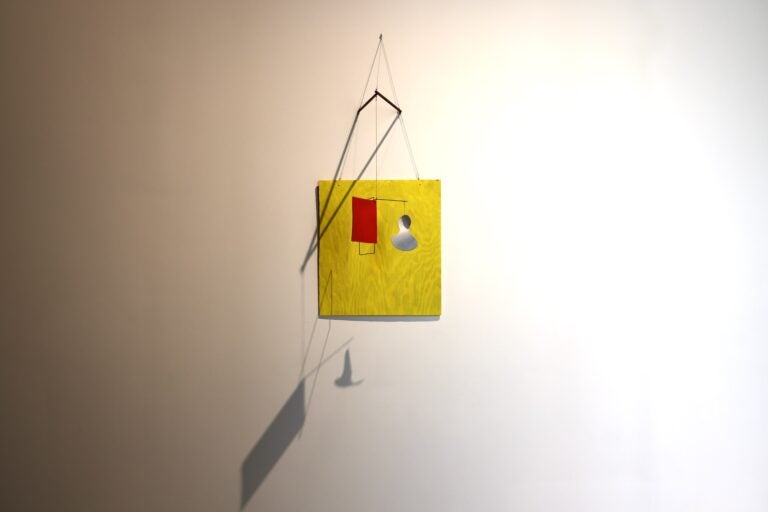

Hallways branch off that show smaller works, many made of wire, and paintings of geometric and serpentine shapes. Visitors explore art-filled passageways, some that lead nowhere or loop back to the large galleries.

A pair of double doors leads to an outdoor garden below street level, where pieces like the 12-foot-tall “Knobs” tower over plantings.

Compared to many museums, Calder Gardens is relatively tight, with 18,000 square feet on 1.8-acre grounds, but the design is more akin to a haunted house composed to host small but intense experiences throughout.

“You experience one moment that then takes you to another one, and every time you have a different sensorial experience,” said Juana Berrío, director of programs. “You have many different cognitive experiences. It’s as dynamic as the building is, as dynamic as the garden is, and of course as dynamic as culture is.”

The sculptures on view at the opening will change. The Calder Foundation plans to rotate sculptures in and out of the Gardens. The actual gardens in the landscape outside are sparse right now, but will fill in, to be cut back periodically and allowed to fill in again.

Alexander Calder’s inspiration for his mobiles was to draw people’s attention to the changing environment in which the object exists, a space that necessarily includes the observer. Rower describes the building made to contemplate his work like a river, one that will not be the same when stepped into twice.

“In three years, you’re going to come back and we’re going to talk about these gardens. We’re going to talk about the light coming in the building. We’re going to talk about an entirely different group of sculptures,” he said. “I want every single time you come to be a different experience.”

On Saturday, the day before the opening, Berrío coordinated a parade down the Parkway to mark the grand opening, conceived by composer Arto Lindsay and featuring local musicians and performers including Pig Iron Theatre, Almanac Dance Circus and the percussion ensemble PHonk! The parade will conclude with a concert by Sun Ra Arkestra in Maja Park.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.