After year one, Philly DA Larry Krasner earns praise from reformers, scorn from victim advocates

After a year in office, Larry Krasner, considered one of the most progressive district attorneys in the nation, sees himself as orchestrating his own movement.

Listen 5:52

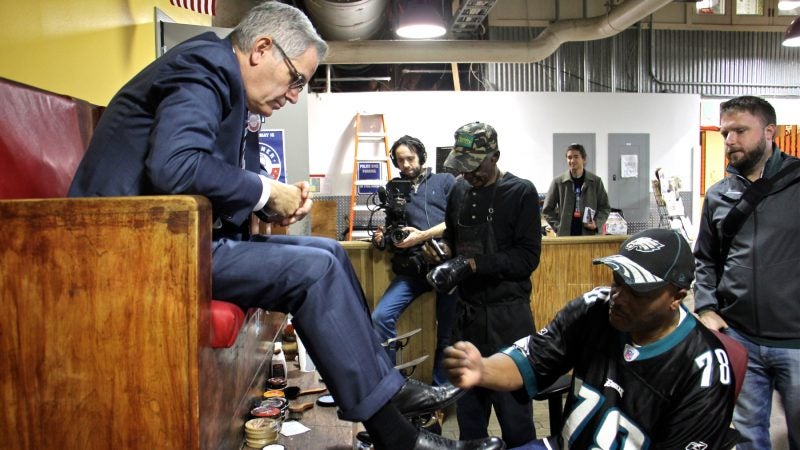

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner is pictured in the District Attorney's Office in Center City on Friday February 1, 2019. (Brad Larrison for WHYY)

Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner sits beneath the gaze of giants.

Above a large blue couch in his eighteenth-floor office are mugshots of civil rights icons Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks. To the right of the photos is a blown-up cover of Time Magazine from 2011, the year it made “The Protester” the person of the year, a nod to the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street.

After a year in office, Krasner, considered one of the most progressive district attorneys in the nation, sees himself as orchestrating his own movement — one that bucks the established rules in cities across Pennsylvania and beyond.

A former civil rights lawyer who ran on a platform of combating the inequalities of the criminal justice system, Krasner vowed to reduce the city’s jail population.

And after his first year, there has been a substantial drop: From about 6,500 inmates the month before he was sworn in to round 4,700 today — a decline of around 30 percent.

After rattling off these statistics, a self-confident Krasner offers his assessment.

“It’s pretty good,” he says.

Krasner’s statistics keep coming. A year of incarceration? He says it costs taxpayers $40,000. Probation? He says it stops being effective after three years.

As he talks, Krasner has a habit of referencing studies and promoting books critical of the criminal justice system, like “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander, which argued that mass incarceration ushered in a new type of legal racial segregation.

On the national stage, this viewpoint from a prosecutor has made Krasner something of a media darling, attracting profiles from the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine and Newsweek.

Jondhi Harrell, executive director of the Center for Returning Citizens, said there is a reason he’s attracted so much attention.

“If you look at what Krasner has done in his first year and you can’t see the sea change in Philadelphia, then you’re just not thinking,” said Harrell, a former inmate who now helps people adjust to life outside of prison. “Frankly, I never thought I would have lived to see this.”

‘Freedom is free’

Well before Krasner came into office, a multi-million-dollar effort by the MacArthur Foundation had been underway to work with Philadelphia officials to drastically cut the city’s jail population. But Krasner credits his policies with accelerating the push, which prompted city officials to close a jail.

How’d he do this?

He told his prosecutors to stop asking defendants to post bail or sit in jail pre-trial for low-level offenses like driving under the influence, resisting arrest and some burglaries.

Krasner said the policy has put a dent in the jail population and has not impacted public safety or the likelihood that a defendant misses a court hearing.

“All our metrics, all of our information at this point, indicate it caused no uptick in crime,” Krasner said. “And it caused no significant increase in people failing to show up. So it kind of looks like that freedom is free.”

Given the success, Krasner said he anticipates adding more criminal offenses to the list of crimes in which his prosecutors will no longer ask for cash bail.

Additionally, Krasner has asked his staff to stop charging marijuana possession regardless of the amount. He also told his 300 assistant district attorneys not to charge sex workers with prostitution if the person has fewer than two convictions.

Caught shoplifting? There is a good chance Krasner’s office will issue a summons, not level misdemeanor or felony charges, which used to be the norm.

These moves have meant Philadelphia prosecutors in 2018 filed nearly 20 percent fewer cases than the previous year, and half as many new criminal cases compared to 2013, according to internal figures from the office.

Krasner wants to continue this trend by diverting more drug users out of the criminal justice system.

In a recent interview with Keystone Crossroads, he mentioned publicly for the first time a plan to expand this program beyond just those caught with marijuana.

“This would apply to heroin. It would apply to crack. It would apply to cocaine,” Krasner said. “There’s just not a whole lot of value in convicting people who are suffering from a disease that is called addiction. There are other ways to be accountable than to make it harder for those people to recover with a good job.”

Similar efforts in Chicago and Seattle have sought to steer opioid users into treatment rather than jails.

A spokesman for Krasner would not elaborate on when the diversion program expansion would be implemented, though it is expected this year.

‘Forgot the oath’

But this, like many of his policies so far, is likely to garner stiff opposition — both from the law and order establishment and from rank-and-file police officers, some who worry his tactics undermine the work of patrol officers.

It is a view shared by police union president John McNesby who claims Krasner “forgot the oath that he had taken to uphold the law.”

In the Criminal Justice Center in Philadelphia, dozens of officers angry at Krasner have been packing hearings in support of Ryan Pownall, a white police officer Krasner charged with murder for fatally shooting David Jones, a black man whom his lawyers say was unarmed when he was killed in June 2017. It is the first time an officer has faced criminal prosecution for an on-duty shooting in the city in nearly two decades.

“Nobody gets a free pass. Nobody gets treated better or worse than anyone else. We look at a lot of cases involving shootings by police of civilians and I think we’re very fair,” Krasner said recently. “This happens to be one where we think a crime was committed, so we brought charges.”

Another unavoidable issue will be continuing to deal with staff morale after 139 D.A. office employees departed after Krasner’s election, according to figures confirmed by the office. Krasner brought on 150 new employees last year. Still, it means that about a third of the staff in one of the busiest prosecution offices in the nation are new hires, creating what sources say is a sometimes tense, unsettling dynamic.

Krasner’s second year in office will also unfold against the background of a surge in homicides and shootings, which both he and Philadelphia Police Commissioner Richard Ross attribute to violence stemming from the city’s opioid crisis.

His critics also say his push to reduce prison populations has hurt victims and their families.

The D.A.’s office has brokered lenient pleas deals with offenders, sometimes without the victim’s family even knowing.

That’s what happened after a man with an AK-47 shot and permanently injured a deli owner in West Philadelphia as he was washing his car. Krasner’s office offered a plea bargain to the shooter that made him eligible for release after 3 years. Following a backlash, Krasner tried to reverse the deal, but a judge said it was too late. The deli owner says he was not kept informed about the case being resolved with a plea offer, which is a violation of state law.

“We did make a mistake, and we owned it,” Krasner said. “We explained that the prosecutor who had the case had not followed office policy.”

In response to such criticism, Krasner has been taking steps internally to better incorporate the families of crime victims. He said his prosecutors were recently trained on a new system that will be in place for all cases to better ensure that victims are contacted during the important stages of a case “to make sure we get useful input from them on their feelings about the case,” Krasner said.

But for some, such efforts should have come sooner.

“I cannot understate what this individual and his movement has done to our family and other families,” said Ace King, son of a slain Philadelphia police officer.

Ace’s dad, Frank “Buddy” King, was murdered days before Christmas in 1998 while he was a patron at a bar. Aaron Smith, now 38 — who was in the getaway car and was one of the five convicted in connection with the killing — was given life in prison as a teenager.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that juvenile lifers deserved new sentencing hearings, Smith was lined up to receive a new punishment that would allow him to leave prison one day.

As that process began to unfold, King says Krasner seemed more focused on securing Smith’s release than he was about being an advocate for the King family.

“We’re not asking to put a needle in this guy’s arm. We’re not asking for this guy to be in life in prison again. We are just saying, keep the victims family in the loop and have their voices heard. And that’s not happening,” King said. “He’s actually muffling and squashing those voices and not being forthright.”

King learned that Krasner wanted to allow Smith to be eligible for parole immediately. King asked Krasner if his office would consider asking a judge to keep Smith in prison for at least several more years. Krasner refused.

“And I asked why? Why are you lowering the threshold?” King asked Krasner during an interaction. “He said, ‘I do not believe that incarceration makes cities safer.'”

In October, Common Pleas Judge Jeffrey Minehart rejected Krasner’s request and ruled that Smith will be eligible for release in 2020.

The road less taken

Krasner’s mandates have caused other friction. He wanted his prosecutors to announce the cost of incarceration at sentencing hearings and a judge reprimanded an assistant D.A. for doing so. Another judge appointed a special prosecutor after one of Krasner’s assistants was found to be too forgiving. And the U.S. Attorney in Philadelphia has threatened to intervene in a violent case where Krasner’s office extended a lenient plea deal.

“He was elected on a platform that differed from the approach that many people in the criminal justice system have traditionally taken, said David Sklansky, a former federal prosecutor who now teaches law at Stanford University. “So it’s not surprising that some people who operate in the system are going to push back against him and think that he’s doing the wrong thing.”

To Anthony Dickerson, the goal of giving more people a second chance at a normal life is one of the reasons he has backed Krasner since his campaign. Dickerson served a decade in prison for selling drugs and now helps people transition back into society after being released from jail.

“Before it was just lock ‘em up and throw away the key,” Dickerson said.

Dickerson does not believe the theory that criminals are newly emboldened to break the law because they think they might find mercy from the new D.A.

“People out in the street, they’re just trying to survive and make money. They don’t vote. They don’t even know who the mayor is, let alone the D.A.,’ Dickerson said. “All they know is: you avoid cops and stick-up men.”

Sklansky, the Stanford law professor, agrees. It’s not reasonable to connect a D.A.’s policies and a city’s crime rate, he said, especially after just one year.

He welcomes Krasner’s approach after decades of what he saw as over-charging and over-punishing thousands of defendants.

“There can be reasonable disagreement about whether declining more cases will undermine law enforcement, undermine deterrence, but I think given how punitive the system has been, it’s hard to argue that that aspect of his operation is out of control,” Sklansky said.

The offices of other district attorneys in Pennsylvania would not comment on Krasner’s first year in office, or whether some of Krasner’s policies would ever spread to other parts of the state.

Krasner attracted attention from other top prosecutors when he withdrew from the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association, calling the group “the voice of the past.”

Greg Rowe, the executive director of the association, struck a conciliatory note when asked about the move.

“Our door is always open,” Rowe said. “While not everyone agrees all of the time, robust discussion among those with varying experience and perspectives are important, welcome, and provide a valuable service to the advancement of justice in every community of the Commonwealth.”

Keeping the public’s support

In his office overlooking Philadelphia — the poorest big city in America with one of the highest prison rates — Krasner says he is doing what he can to be a counter force.

Moving forward, Krasner says a major priority for his office in 2019 is reducing the number of people in the city under court supervision.

“We have 40,000 people on probation and parole and New York City has 12,000 people, and New York City is five or six times bigger than we are, depending on how you count it. Why?”

Krasner knows it won’t be easy to reverse decades of law-and-order policies that created the current landscape.

But experts say it’ll be even harder if Krasner can’t find the support of crime victims and if violence on the streets is not contained.

Krasner thinks a more insurmountable issue than crime on the streets is battling the perception that crime is always on the rise.

“For 30 years, the public has believed crime has been going up based on chit-chat in the community, watching Law and Order on TV, reading sensational articles in the media about particular horrible crimes,” Krasner said. “But fear is not real. Fear is fear.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.