After five years, advocates praise Philly pre-K, blame tax opponents for missed enrollment targets

It’s been five years since Philadelphia expanded its pre-K program, funded by a controversial tax on sweetened beverages. Why has it fallen short?

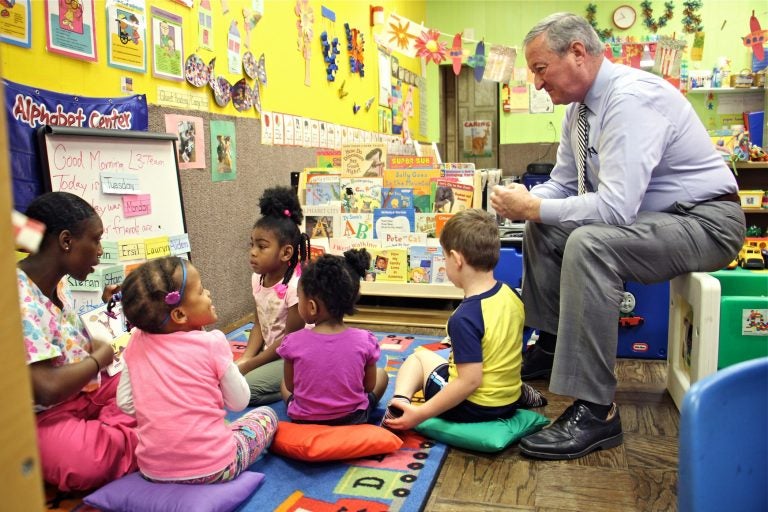

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney sits in on a preschool class at Little Learners Literacy Academy in South Philadelphia in 2016. Pre-K expansion was one of Kenney's top campaign promises. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Wednesday marks the five-year anniversary of the legislation enacting Philadelphia’s expanded pre-K program, funded by Mayor Jim Kenney’s controversial tax on sweetened beverages.

Since 2017, PHLpreK has served 10,000 children in over 130 locations across the city. The program has grown from serving 2,000 students a year to 3,300 this past year. In September, the city expects to serve 4,000 students.

Mai Miksic, early childhood education policy director for Public Citizens for Children and Youth, spoke at a press conference outside Little Einsteins Early Learning Center in Germantown on Wednesday, celebrating the occasion.

“[PHLpreK] has provided high-quality early childhood education for 3- to 4-year-olds,” said Miksic, “helped parents get to work, and has helped women and men of color run their small businesses.”

Jana Taylor, owner of Little Einsteins, praised the program.

“We have been able to reach many more children, and provide many more resources,” said Taylor, who started the school 12 years ago and just graduated a pre-K class of 16 students.

A 2020 University of North Carolina study showed how Pennsylvania’s Pre-K Counts program gives a meaningful boost in some core skills.

Katherine Davis, principal of Charles W. Henry School in Mount Airy, has noticed a difference in students who enter kindergarten with pre-K experience based on the Philly program as well.

Charles W. Henry offers two pre-K programs, Davis said, and students learn social-emotional skills and foundational skills in reading, writing, and math.

“Oftentimes on the first day of school, we joke that it’s very difficult for parents, there are lots of tears,” said Davis. “But when kids have gone through pre-K we see the happy waves, they say goodbye, and they transition into the classrooms.”

Little Einsteins teacher Ingrid Catlin, 80, tied her career with her time fighting for racial integration. She was part of the sit-ins to desegregate a Woolworths store in 1960 in Greensboro, North Carolina.

For her, this is about removing barriers to education no matter a family’s income.

With Philly pre-K, “everybody comes,” said Catlin.

Public Citizens for Children and Youth executive director Donna Cooper also tied the fight for universal pre-K to the civil rights movement.

“If we want Black and Hispanic children in the city to have a shot at the equal future of their white peers, we need pre-K,” said Cooper.

Overall, the pre-K program has fallen short of Mayor Kenney’s promises when he first proposed the soda tax. His initial goal was to serve 6,500 students a year.

And even that number is only a fraction of the total children in need. According to the city data from when Kenney was touting the tax in 2016, more than 17,000 low- and middle-income kids don’t have access to high-quality, publicly funded pre-K.

Anthony Campisi, a local spokesperson for the Ax the Philly Beverage Tax Coalition, said the pre-K program’s falling short of expectations should give consumers pause.

“The tax never lives up to its promises, though it always hurts working families, small businesses, and their employees the hardest,” said Campisi.

Soda companies have fought hard against the tax, as beverage sales have fallen in the city.

Cooper said that is part of what explains the lower-than-anticipated pre-K numbers. Kenney’s plans were delayed because of a lawsuit from soda and grocery companies in an attempt to stop the soda tax in 2018.

The state Supreme Court eventually upheld the tax, but, according to Cooper, the suit caused the city to wait a year and a half before rolling out funds to pre-K programs.

After that, Cooper said, providers needed a “ramp-up period” to expand the capacity of existing pre-K programs and hire enough faculty “prepared to do the high-quality programming.”

Revenue from the soda tax has also decreased during the pandemic. It went down from $76 million in 2019 to $70 million in 2020.

By the 2022-23 school year, the city hopes to reach a total of 5,000 students.

Mount Airy resident Raina Prescott, parent of a graduating pre-K student at Little Einsteins, said her family is living proof the program is working.

Prescott lost her job two years ago, when she was diagnosed with Graves’ disease, an immune system disorder. She was working at the University of Pennsylvania when she got sick and suddenly lost all of her income.

So she applied for the free program. “God is good, I was able to get her in there,” Prescott said.

Her daughter, Brooke, 5, had a speech impediment when she first started, but thanks to a speech therapist she benefited tremendously, Prescott said, and received the “most improved” student award this year at school.

“She’s come a long way,” said Prescott. “I’m really proud of her.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.