Want to expand pre-K? Better put it in the right places

Listen

Mayor Jim Kenney visits with children at Little Learners Literacy Academy in South Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

By the city of Philadelphia’s count, more than 17,000 low- and middle-income kids don’t have access to high-quality, publicly funded pre-K. Money from the new soda tax is supposed to help close that gap. But just because there’s more demand than supply doesn’t mean parents will necessarily rush to fill the new seats.

That paradox is rooted in how parents choose pre-K for the kids.

When we think about school choice we often think about the K-12 sector. And in the K-12 space, quality heavily influences the choices parents make. Open up an awesome public school — or at least a school perceived as awesome — and parents will gladly flock to it. If their kids have to travel a little further to attend a better school, so be it. Indeed families often orient their entire lives — where they live, how they commute to work, etc. — around finding the best school for their children.

It’s a safe bet that if the city of Philadelphia opened scads of new high-quality schools, it would have very little trouble filling them.

Pre-K, however, is a different story. To understand why, you have to meet folks like Darlene Williams, who lives in North Kensington.

Williams’ grandson, Amir, is 5. For the last two years he’s attended Candy’s Kids Learning Academy, a small, storefront operation located about 500 feet from the row home shared by Williams, her daughter, and Amir. Candy’s Kids opened shortly before Amir started attending, and is still trying to move up the state’s quality-rating system. It has just one star out of four on the Keystone STARS rubric, according to state records. Centers must have three stars or higher to be considered high-quality by the city. (The Williams family, by the way, loves the care at Candy’s Kids. Amir is a particularly big fan.)

Darlene Williams and her grandson, Amir. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Darlene Williams and her grandson, Amir. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Before switching to Candy’s Kids, Amir went to Brightside Academy, a major pre-K chain with locations all across the city. The Brightside location Amir attended was a STAR 3 facility, meaning it met the city’s gauge for high-quality. But it was located about a half-mile from where Williams lives. That meant climbing aboard a bus every morning, dropping Amir off, climbing aboard the Market-Frankford line, and shuttling to her office job near Independence Mall.

Candy’s Kids, though, is a quick jaunt away. There are no more messy morning commutes.

“When we’re running down to the wire, it’s really good,” says Williams. “ It is very convenient, and I love it.”

Convenience is king

Years of research shows that folks spend relatively little time looking for early childcare options, often less than a day. And when guardians do choose they’re more likely to prioritize practical concerns like safety, cost, and location. Low-income parents, in particular, place a higher emphasis on practical criteria when selecting a pre-K center. In many cases, parents will choose unregulated home care facilities over more established childcare centers.

“The research is very clear that parents put a high priority on convenience,” says W. Steven Barnett, Director of the National Institute for Early Education Research. “Because they to work with their work schedules, because they’re very reluctant to have their kids spend a lot of time traveling.”

And that makes perfect sense, says Diane Castelbuono, head of the Office of Early Childhood Education for the School District of Philadelphia.

“Anybody who’s ever had kids — and a 3- and 4-year-old — you know it’s hard getting out the door in the morning,” says Castelbuono. “And walking to school with a 3- or 4-year-old is about three, four, five blocks, not much more than that.”

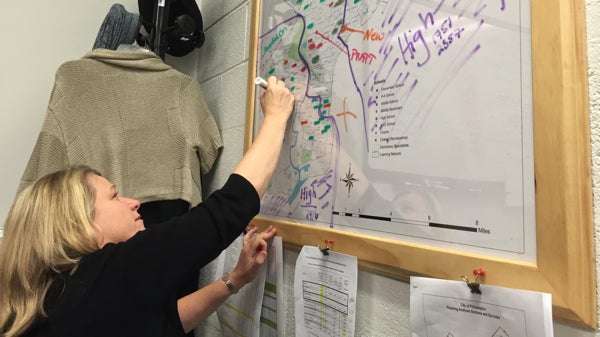

Diane Castelbuono, director of pre-K for the school district writes on a map that shows where each pre-K site in the city is located. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Diane Castelbuono, director of pre-K for the school district writes on a map that shows where each pre-K site in the city is located. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Plus, there’s no transportation infrastructure for the early childhood years, meaning no big, yellow school bus to scoop the kiddos every morning and unload them every afternoon.

Most in the early childhood advocacy community agree that public investment in pre-K only pays off if kids are in high-quality facilities. Kids in low-quality facilities fare no better in the long run than kids who didn’t attend pre-K.

Attracting students

This creates a challenge for cities like Philadelphia. One can’t simply introduce scads of new high-quality pre-K centers and expect parents to come flying in the doors. Instead, a city like Philly has to put new options in the exact neighborhoods where families will use them.

“You have to be pretty granular,” says Castelbuono.

Castelbuono runs the largest network of pre-K centers in the city, serving almost 10,000 kids combined. Castelbuno’s centers are some of the highest-rated around, and yet even the school district has to keep a close eye on each of its facilities to make sure each available seat gets claimed.

To help visualize the challenge, Castelbuono points to “the map.”

“The map” is a layout of Philadelphia, dotted with little splotches of colored dry erase marker. Each one corresponds to a pre-K site run by the school district. The shades signify how full each site is–green for packed full, red for empty seats, and orange for those in danger of going from green to red. Amid the swirl of colors, there’s a lesson about the chaos of trying to track pre-K enrollment patterns.

“There’s a red and there’s a green, and they are four blocks, five blocks from each other,” Castelbuono says, pointing to a swath of West Philadelphia. “Here’s a red and a green, and they’re six blocks from each other. And that’s really where you have to get into the neighborhood and say, ‘What is happening?’”

When parents prioritize convenience, it can become really hard to match supply and demand. An apartment complex goes up, for instance, and demand skyrockets — but only in a very specific neighborhood. Locate a new “high-quality” center one mile from where the kids are — or, for instance, in an area where kids have to cross a busy street every morning — and parents might choose a “low-quality” center instead.

The bigger the city, says Barnett of Rutgers University, the more likely these sorts of troublesome, low-attendance pockets will bubble up.

The push from City Hall

Philadelphia is one of those big cities, and it wants to add 10,000 high-quality pre-K seats over the next five years. So how will officials make sure those slots don’t lie fallow? For starters, the city is going to do a lot of the detailed mapping that the school district already has to do.

“We’re not likely to partner with a provider that’s located in an area that’s already really well served. So that’s a huge factor, but it’s not the only factor,” says Anne Gemmell, who’s heading the pre-K push for Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration.

The city also plans to create an online tool in the next 18 months so parents have a better idea of the centers in their neighborhood and can more easily measure the quality of one against the quality of another. That’ll be part of a broader marketing push to convince families to think differently about how they choose childcare.

“We’re building on efforts from the previous administration to raise awareness around quality and the importance of quality and give parents the tools to recognize quality so that more parents would think about going a little bit out of their way,” says Gemmell.

In this case, getting parents to go a little bit out of their way could wind up making a big difference in the city’s push to make good pre-K more accessible.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.