A summer of catch-up: How Delaware students are making up for time lost to COVID-19

Some students in Sussex County have worked through the summer to catch up on time lost due to the pandemic.

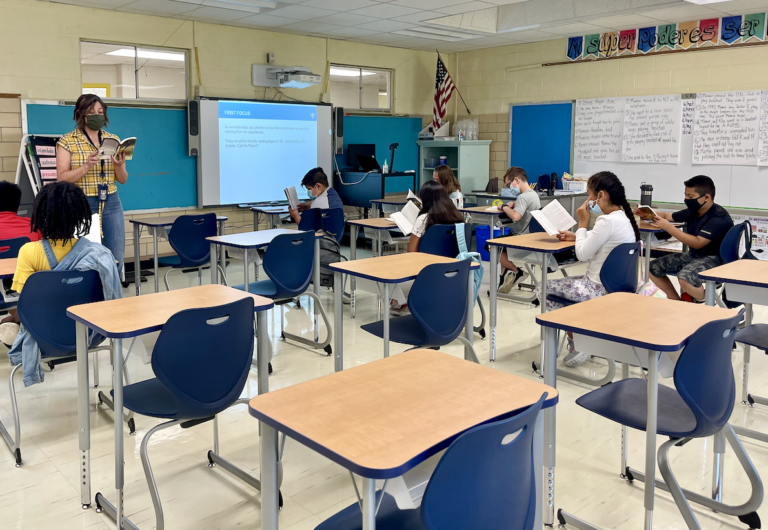

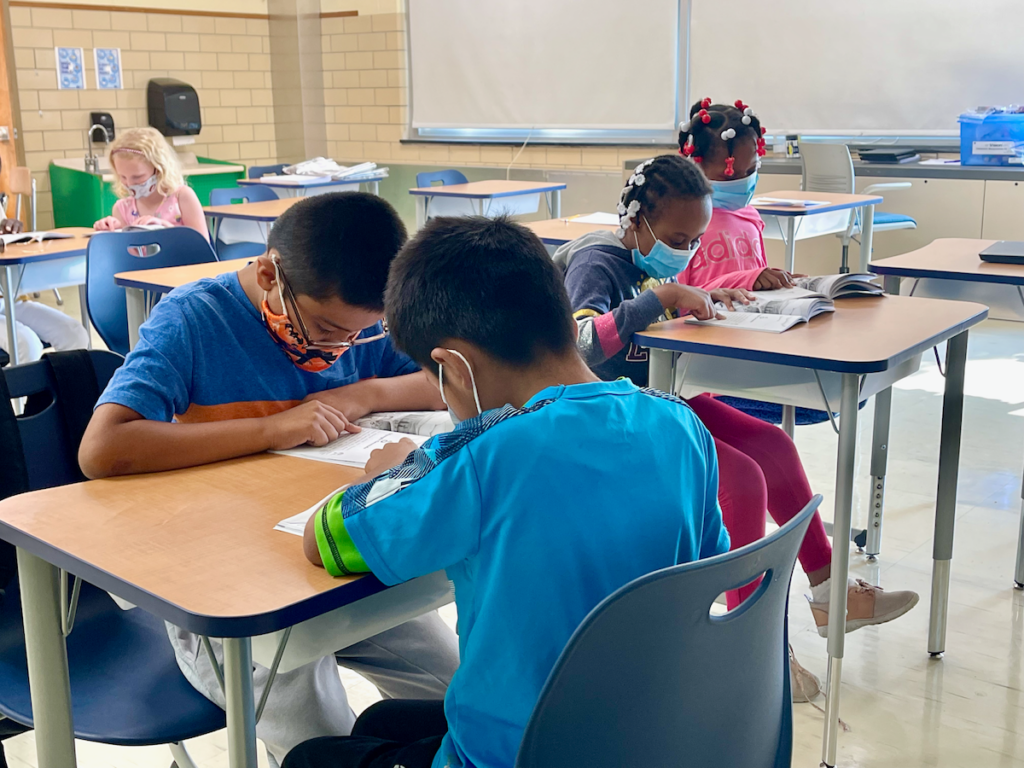

Students in grades three through five read paragraphs from a book inside a classroom at Seaford Central Elementary School. (Johnny Perez-Gonzalez/WHYY)

Large blue and yellow dots on the hallway floors at Seaford Central Elementary School remind the young masked students that they must continue to practice social distancing. It’s midsummer, the COVID-19 pandemic that cost them in-person learning for most of the previous year has abated somewhat, but the dots serve as a reminder that the threat is not over.

Inside a classroom, pairs of students alternate reading paragraphs from a book and discuss how the author employs illustrations to help them envision the competition at the Olympic games. In another part of the room, third- through fifth-graders — part of the school’s Spanish immersion program — are reading a book in Spanish.

Over in Georgetown, the classrooms at the First State Community Action Agency are more crowded than most years. This has not been a typical summer. The 15 students, in the third through fifth grades, are at their desks, stumbling over words as they take turns reading a story aloud, paragraph by paragraph. They’re working with their teachers to recover some of what they lost during a year spent mostly outside their classrooms and put themselves on better footing to start their new school year. One room away, younger students, split into groups of four, work on their projects, bubbling with enthusiasm eager to be back in a classroom.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck Delaware in March 2020, thousands of students, as well as parents and educators, suddenly experienced a variety of new challenges as they navigated through fully remote learning, a transition to hybrid instruction, and finally, a return to traditional classrooms.

Those challenges extended well beyond the adjustment to unfamiliar technology — technology that was not always easily accessible in rural areas of Sussex County, and especially to Latino and low-income families.

School districts experienced challenges like coping with the social and emotional impacts of the pandemic, students of color falling behind in their education and assignments, and parents struggling with the transition to technology.

Because the school districts are also community hubs, they were asked to help families with a host of issues like food and housing. assistance.

After finishing the 2019-20 school year in a remote learning environment, North Georgetown Elementary in the Indian River School District was among those that transitioned to a hybrid structure last fall, with students returning to their classrooms twice a week and receiving the rest of their lessons online.

Lindsey Perez, a student-teacher at North Georgetown Elementary, said that seeing these students in person for such a limited time slowed their educational development.

“It definitely puts students who are already behind, behind even further,” Perez said.

Everything felt empty last fall, teachers across Sussex County said, describing having no more than five to 10 students in their classrooms — in accordance with federal Centers for Disease Control guidelines — when they were accustomed to working with groups of 20 to 25.

Summer learning fills the gaps

Bolstered by federal funding through the American Rescue Plan Act, school districts this year implemented major expansions of their summer learning programs.

According to the state Department of Education, more than 10% of the state’s public school enrollment was participating in a summer program. While many students at elementary and middle school levels had access to online learning programs, most of the instruction was taking place in person, either in schools or at partnering facilities, like those operated by the First State Community Action Agency (FSCAA).

FSCAA provides programs to help communities of color throughout Sussex County, including a Summer Enrichment Camp and an after-school program. With students returning to in-person learning, FSCAA staff members say they received a first-hand look this spring and summer at the challenges that schools and parents are experiencing.

When the pandemic hit, FSCAA shifted its program from one that was only after school to one that served students all day long. Overall, it enrolled 151 students, from kindergarten through high school, giving youngsters a place to be supervised and receive academic support while their parents were at work.

“We became the school,” said Dr. Sandi Hagans-Morris, FSCAA program director. If parents chose remote-only learning for their children, they would come to FSCAA and stay there all day instead of at home. If students enrolled in a hybrid program, they would come to FSCAA on the days that they were not in their regular classroom.

Being able to work with the students in person makes a big difference, Hagans-Morris said. By the time many students enrolled in the FSCAA program, they had not only a bundle of uncompleted assignments but also emotional issues associated with the stress and isolation of the pandemic.

“We were looking at students going through some emotional changes. A lot of them were having a lot of different thoughts, a lot of different behaviors, COVID really impacted them mentally. So we were looking at some traumatic things going on,” she said. “One kid came in with 180 assignments. The mother said she has not done anything on Zoom since school started, and this was February. We had to catch her up with all her assignments.”

Instructors at FSCAA recognized that students of color needed more assistance around literacy comprehension and in the STEM areas of science, technology, engineering and math. The summer enrichment programs emphasized having students read books and doing activities relating to the reader.

“Parents were very excited. We’re getting kids to read books, we have tons and tons of books that go along with the program, activities that go along with the books, and the kids will be reading books every day,” Hagan-Morris said in midsummer. When students return to their classrooms and take the annual state assessments next spring, “their scores should go really high,” she predicted.

Combating emotional challenges

Staff members in Indian River and some other Sussex districts are finding students excited to be with their peers again. But despite the joy of being back together, many of those students are struggling to regain their learning skills and practice appropriate social and emotional interactions.

Gemma Cabrera, a special educator at North Georgetown Elementary in Indian River, said that students appear withdrawn and are not showing any emotions. Teachers have told her that students are not interacting with each other as they did before the pandemic. Cabrera said she misses the reactions she was accustomed to getting from students when she bumped into them in the hallways.

“I’ve been a teacher, and I feel that in my gut, a child in first, second, and third grade should be smiling,” Cabrera said. “You come to school to learn, to be with your friends.” She said students seemed to be “completely withdrawn from their social life.”

Parents also say they have noticed interpersonal issues with their children because they have not been with their friends and classmates for many months.

“There seems to be a lot of issues, of not getting along, and some of that is normal, but interpersonal stuff where the kids just had six to eight months where they were not around any other kids,” said Cassidy McDaniel, a parent in the Cape Henlopen School District.

Improving multilingual communication

Communication with parents, especially those from Latino and low-income families, has been a constant issue for all school districts throughout the pandemic. In-person parent/teacher conferences could not be held last year, so school districts had to find different ways to build relationships with parents and bridge that communication gap. The challenge was greatest for English-speaking teachers trying to connect with parents who speak only Spanish or Haitian Creole.

According to the state’s school data website, North Georgetown has an enrollment of about 800 students, where 78% are Latino. North Georgetown Elementary quickly recognized it would have to make adjustments with most of those students learning remotely during the past school year, Principal Samantha Lougheed said. Communication remained an issue with the 250 students enrolled in the school’s summer program. Almost all those enrolled are students of color, and 80% of them are Latino.

North Georgetown’s solution was to use a text messaging app that immediately translates messages into the recipient’s language, Lougheed said.

“Our teachers have said that they have had more communication with their parents this year than they ever have,” she said. “We have always had great parent communication. But I think what is going to come out of this, is an even closer relationship between our families and our school.”

West Seaford Elementary School took a slightly different approach, using a language hotline and a variety of online platforms. Principal Lauren Schneider said one of those platforms, called Seesaw, enables teachers to record and share what is happening in class and allows parents to communicate with their children’s teachers. When using the app, parents can see their child’s “journal,” showing the work the child has done and comments given by teachers or other peers. It’s another way for teachers and parents to communicate effectively, she said.

In the Milford School District, Dr. Bridget Amory, director of student learning, said relationships with parents pivoted in a different direction, with an increased reliance on online meetings with parents as well as “using a variety of communication tools such as text, phones, and social media.”

Indian River parents say they are happy with the communication between non-English speakers and their children’s teachers. Most of them want teachers to continue using text messages to communicate with them.

Celia Gonzalez-Santizo, a Georgetown resident with three students in district schools, said being able to text message her kids’ teachers has helped develop a closer relationship with them. She knows that if she has a question about her kids’ education, teachers are easy to reach and provide a response.

“Ahora fue más fácil porque tengo comunicación siempre. Cómo iban en sus estudios? Ellos me mandaban mensaje, como que para mí fue mucho mejor,” Gonzalez-Santizo said. “Si uno necesita saber algo de nuestros hijos, manda uno el mensaje y nos contesta.”

“Now, it was easier because I always have communication. How were they doing in their studies? They sent me a message, as it was much better for me,” Gonzalez-Santizo said. “If one need to know something about our children, one sends the message and they respond.”

Better communication brings new challenges

With the amount of communication between schools and non-English-speaking parents on the rise, those parents are becoming more comfortable bringing non-school issues to their attention, according to staff members at North Georgetown Elementary and some other schools.

“We can only help so much,” Cabrera said. “Problems like evictions or problems like finding food or being able to assist with medical care, you know, are really kind of beyond our scope of help,” she said.

Cabrera and Lougheed said they try to provide families with as many resources as possible, but there is only so much they can do. Cabrera said they understand the different ramifications of other problems that impact a child, but their primary mission is to educate them.

Among the issues that Sussex schools experienced, the most common was the lack of student attendance with online learning, either because families did not have access to the internet or did not know how to use technology.

The Woodbridge School District in northwestern Sussex found that about 30% of its families had no access to the internet. However, this changed when the state Department of Education used federal CARES Act funds to provide an internet hotspot to serve hundreds of families.

Once the hotspots were set up, in Woodbridge and other parts of the county, schools hosted in-person meetings for parents to teach them how to use the technology and online platforms.

“We had multiple families every single day coming in here and sitting with staff members to learn the platforms online to be able to help their students at home,” Lougheed said.

In-person learning returns this fall

Officials in both the Seaford and Milford school districts are working hard to have their personnel ready for a return to full in-person learning this fall. Resumption of in-person instruction, they say, will reestablish critical structures for students and families.

While some students may carry more responsibilities than others, many are optimistic about the start of the new academic year — especially the rising middle or high schoolers.

After wrapping up her studies at North Georgetown Elementary with an academic year of virtual learning, Yareli Gonzalez-Santizo is excited to go back to seeing her teachers face-to-face at Georgetown Middle School. The past year was quite stressful, she said, trying to use Zoom for her own classes while also helping her 7-year-old brother Ethan Orozco.

“I’m excited because I want to meet the new teachers I’m going to get,” she said. “I just want to meet new friends, I want it to be in-person since it’s going to be my first year for middle school. I just want to have that experience.”

This article was produced with the support of a grant from the Delaware Community Foundation. For more information visit https://www.delcf.org/journalism/

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)