A certified ‘champion,’ Philly’s Great Beech is dying, over 150 years after it was planted

Philadelphia’s champion tree, The Great Beech, measured above 100 feet tall, making it the tallest of its kind in the United States. It’s slowly dying.

The Great Beech once had five boundless trunks — some believe it is a single tree, others believe it began as five individual trees planted close enough to join. (Courtesy of Christina Moresi)

On my first visit to The Great Beech in March 2021, it was already dying.

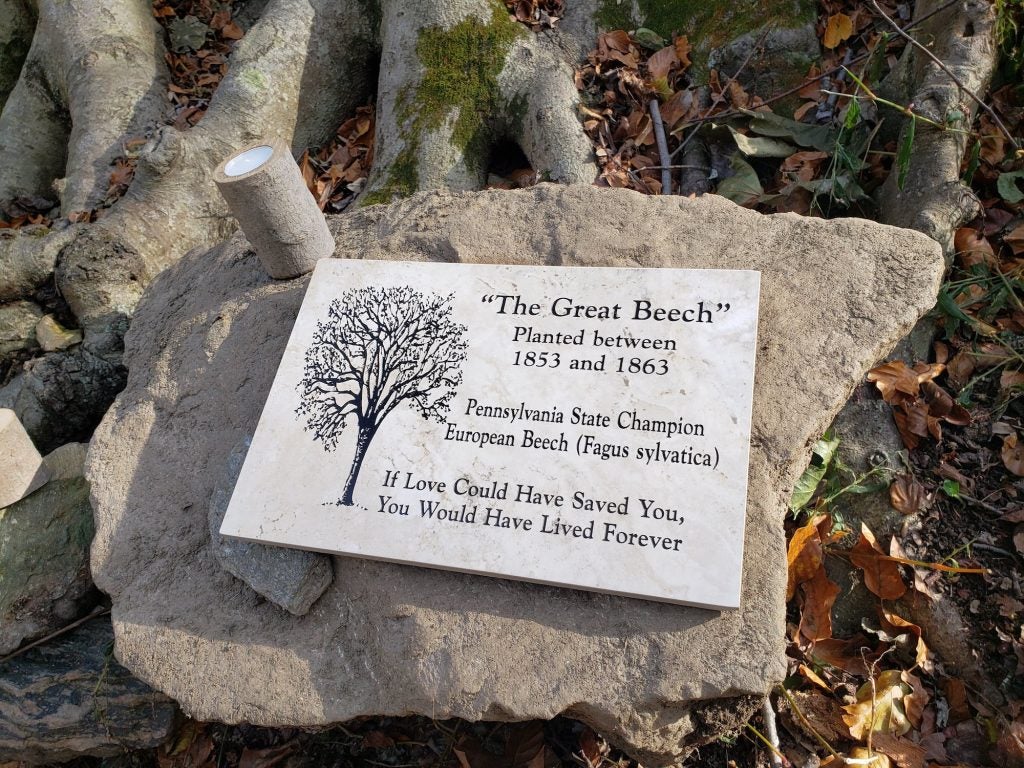

The Great Beech is a spectacular tree — a European Beech that was planted between 1853 and 1863 in Philadelphia.

Those who know the tree say it has always been an icon, but it gained a new level of celebrity in 2006, when it was designated a champion tree. Champion trees are a register organized by America Forests for the largest tree of each species in the country. When it was certified in 2006, The Great Beech measured above 100 feet tall, making it the tallest European Beech in the United States. As of 2020, The Great Beech still holds its title, though it hasn’t been measured since 2017. Since then, it has lost both limbs and height.

Although it is nearing the apex of its longevity, The Great Beech’s decline has been exacerbated by a constant stream of human activity.

“It was OK, you know, a few people here, a few people there,” said Jason Lubar, associate director of urban forestry for the Morris Arboretum. “But then more and more people started visiting,” he added. Those people trod on the beech’s shallow roots, causing soil compaction. They carved their names into its bark, making it vulnerable to diseases.

The Great Beech once had five boundless trunks. While some believe The Great Beech is a single tree, others believe it began as five individual trees planted close enough to join. Last year, two of the trunks grew and shed leaves, meaning the rest were already dead. The blossoming of spring would reveal which, if any, had survived the winter.

In late March the tree was bare.

I wrestled with my instincts as I stared at it. I wanted to be as close to it as possible, to lay my hand on its bark. But I knew that precise impulse had propelled others before me to hasten the tree’s destruction. Nobody should be allowed near this tree, I thought. Lubar, who worked and lived at what is now the Wissahickon Environmental Center until 1996, explained the tree’s draw as a simple one. “People just like big trees,” he said.

The tree was in good health in the ‘80s, he remembered, but then it began its decline. Lubar contended that nearing the end of its life was natural for a European Beech of this age, but that the damage of human impact has quickened its decline.

There’s a plaque on The Great Beech, anchored between its many roots. It reads, “If Love Could Have Saved You, You Would Have Lived Forever.” And maybe it’s true. Those closest to the tree speak of its long demise like a friend. But do the rest of us know how to love nature? We love the beach by snatching its seashells. We love the reefs by marinating them in sunscreen. We love the flowers by picking them. We love them all to death.

“There are treatments that we use to sort of strengthen the tree that can help expand the life of the tree,” Lubar told me. “But since this tree was not under anybody’s arboricultural care, that didn’t happen,” he said. “It’s a park tree and the park didn’t have the resources to do that.”

A dying tree still breeds life

On my second visit to The Great Beech, I went with Christina Moresi and Stephanie Robinson, environmental educators with the Wissahickon Environmental Center. Moresi, who has worked at the park for 15 years, shared Lubar’s belief that the tree’s lifespan was shortened by people interacting with it. She did not, however, share his outlook. Moresi explained that with stormwater rushing in from the parking lot and visitors disregarding park policies, there wasn’t much that could be done to protect the tree. Fencing it off was never an option for her, she stressed.

Moresi wanted people to interact with the tree. She wanted children to hug it. It was a charitable perspective, given all she had seen. She told the story of once finding the proposal “PROM?” carved into one of the beech’s branches. “When I first saw that I was like ‘I swear to god I hope she punched him,” she said.

When I asked her why more interventions hadn’t been put in place, she paused. “It really is just a matter of letting nature take its course,” she said.

It was May then, and only one of the tree’s branches held leaves. Moresi admitted that had been a disappointment. However, she was quick to point out that a dying tree, or even a dead one, breeds life.

A dead tree, called a snag, hosts bacteria, fungi, insects, and animals. Woodpeckers peck it, raccoons nest in it, and mushrooms grow up and down its branches. On the dead limbs of The Great Beech, an entire ecosystem is churning.

Nearby, another beech, named Baby Beech, grows.

Baby Beech sprouted up from The Great Beech’s extensive roots, and has been called its “successor.” The little tree is growing taller in a thicket behind The Great Beech, nearly undetectable.

Like their predecessor, the beeches that have sprouted around The Great Beech are not fenced off. Sitting beside them, I watched the birds and insects whirl around the beech’s limbs, dead and alive. The branches that once shaded the area have fallen, and plants of all kinds are growing in the new flood of sunlight. The tree’s decay is a generous one. The Great Beech may have been loved to death. But those who visit it, myself included, learn that we can love the natural world in death as well.

As I sat, hikers ambled by on the trail, all of them stopping for a moment to look. “What kind of tree is that?” one woman asked me. “A European Beech,” I said, a tinge of kvell in my voice. I watched as the group craned their necks up, up, up. As they walked away, I heard one say to the others: “Wow.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.