4 takeaways from Delaware’s most comprehensive overdose death study

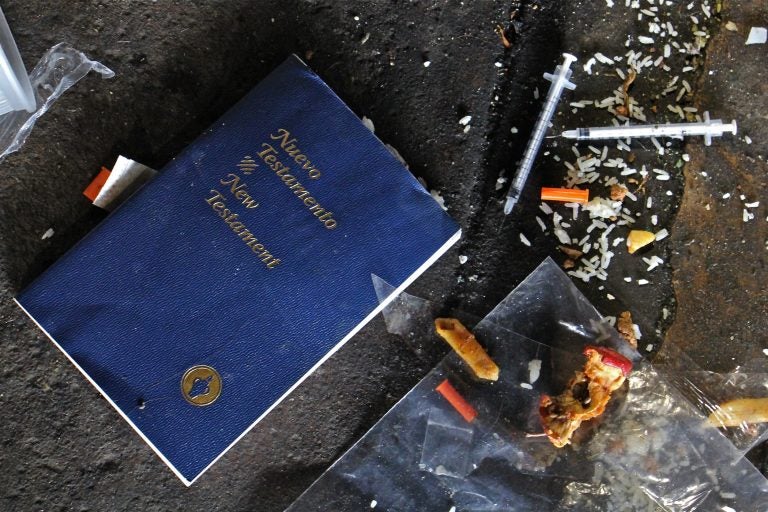

The state has developed a demographic snapshot of those who died of drug overdoses in 2017. It will be used to try to reduce future opioid-related deaths.

The state has developed a demographic snapshot of those who died of drug overdoses in 2017. It will be used to try to reduce future opioid-related deaths. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Delaware has the fifth-highest overdose death rate in the nation, something state leaders are working in a number of ways to reduce. With that goal, they have compiled information from 12 multi-agency data sets to create a picture of who is dying from drug overdoses and figure out the best ways to target those most at risk.

“Each one of these deaths represents a mother, father, sister, brother, friend, colleague who was lost,” said Kara Odom Walker, who heads the state Department of Health and Social Services. “It’s a constant reminder to us at the state every time we see another death that we have more to do.”

The report focuses on overdoses in 2017, when 346 people died. In 2018, 400 people died of drug overdoses.

Overdose was most common among middle-aged, single, white men

Those who died from overdose were predominantly men who were middle-aged, single, and white. Men accounted for 67% of all overdose deaths in 2017, and 79% of those who died were non-Hispanic whites. Nearly 60% of overdose victims never married, and 55% had at least a high school diploma or a GED.

They were also more likely to work with their hands, in either the construction or maintenance and repair industries. Of the men who died, 36% worked in construction, while 9% worked as mechanics, in HVAC repair, or in maintenance. Women who died were more likely to be unemployed, with 33% of victims not working. The top two industries for working women who died of overdose were food service (14.7%) and office support (12.8%).

Most victims had a chance for intervention

The majority of overdose victims, 81%, had an interaction with some part of the health care system in the state within the year prior to their deaths. More than half visited Delaware emergency rooms within a year of their deaths, and 43% had encounters with emergency medical services within that year. The hospital or EMS visits weren’t necessarily related to drug use. About 23% visited the emergency room for mental health-related diagnoses, and only 10% had previous drug overdose-related ER visits. Many were visiting the ER to deal with pain. In July, the state released a study of 56 overdose deaths from 2017 that showed half of Delaware’s OD deaths happened within three months after ER visits.

In light of the interaction so many overdose victims had with health care providers, the state is stepping up its efforts to get doctors to be more consistent in surveying their patients about illicit drug use. That’s not happening in as many doctors’ offices as you might expect, said Odom Walker, who also works as a family physician. “That’s why we really need this universal idea of asking all adult patients,” she said. “Knowing that this is an important moment to identify.”

Another high-risk group for overdose were those leaving prison. Of those who died of an overdose, 25% were released from incarceration within a year of their deaths, and 30% of those who died were on probation or parole within that year. Twenty-two percent were on probation and parole when they died.

To ease the transition out of prison, the Department of Correction has partnered with the Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health to help inmates who are considered at high risk for opioid use. Since March, 445 have been screened and educated about the risk of overdose and the availability of treatment after being released.

“What a critical partnership this has been,” said Elizabeth Romero, director of the substance-abuse division. Later this year, the state plans to launch a van program to provide transportation to inmates to go to treatment immediately after being released from DOC custody.

Opioids led all drugs in overdoses, but cocaine is rising

The face of the opioid crisis is changing. Ten years ago, almost all Delaware OD deaths were the result of prescription drugs such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. Today, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids are the leading cause of overdose deaths, responsible for 72% of all 400 deaths in 2018.

And even though the number of opioid prescriptions dropped 25% from 2013 to 2017, Delaware still has the 18th highest opioid prescription rate in the nation. The number of residents diagnosed with opioid use disorder has climbed from 6,000 in 2006 to 11,000 in 2017.

Opioids were responsible for 84% of all overdose deaths in 2017, but cocaine was responsible for the biggest percentage of deaths among both black males (52.6%) and black females (56.6%).

Opportunities to help were missed

When reading the death reports of all these people, Romero said, she sees chances that were missed. She looks at their stories, to find opportunities when someone could have intervened in each victim’s life that weren’t taken. That’s especially the case with OD victims who had interacted with the health care system in the year prior to their deaths.

“Where could a person notice this was happening? Where was someone that could have taken that moment to take a hand to say, ‘I am here for you, I see you, and I want to help you,’” Romero said. “Part of this journey is really helping to find out where are those moments to connect to someone that says, ‘I care.’”

Those who are in recovery from substance abuse disorder can be a powerful tool to help people who are struggling. That’s why there are now peers working in every emergency room in the state, to connect with those at risk for overdose.

At Delaware’s largest hospital system, Christiana Care, peer help has been in place for more than 10 years. “To put peers in a place where we had a really unique, reachable moment with patients coming into the health system,” said Erin Booker, vice president for community health and engagement at Christiana Care. “It is a fantastic program.”

“We can give anyone help,” said Lt. Gov. Bethany Hall Long. “It’s OK to not be OK, and when you’re not OK, please ask us for help, we can get you help.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.