35 years after MOVE, homes that Philly bombed for sale

Developer AJR Endeavors is wrapping up the rebuild of the block that Philadelphia bombed and allowed to burn in 1985.

The brick exterior of 6225 Osage Avenue, one of the 36 homes destroyed in the MOVE bombing and newly renovated. (AJR Endeavors)

On the 35th anniversary of the MOVE bombing, a West Philadelphia neighborhood partially destroyed by the city will finally be rebuilt.

What started as a multi-year clash between the Philadelphia Police and a Black liberation group, known as MOVE, ended when police dropped a bomb on the group’s compound on 6200 Osage Avenue, destroying 61 rowhouses and causing many deaths.

While the city eventually rebuilt many of the homes, in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood, these new structures were plagued by shoddy construction. Many were eventually abandoned.

The Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority undertook the process of rehabbing or rebuilding this second set of homes starting in 2016, following complaints from neighbors frustrated by problems with the 36 vacant city-owned properties.

Now, after the unexpected hurdle of the coronavirus pandemic, workers are finishing the final two homes. Thirty-two of the 36 split-level homes on Osage Avenue and nearby Pine Street, which was also damaged during the bombing, have already sold.

“The project is just about wrapped up,” said PRA spokesperson Jamila Davis. “Thirty-four of the 36 homes are completed and the last two will be ready for final inspection within the next 30 days or so.”

Davis said the pandemic slowed the process of moving the last few homes. All of the homes, developed by AJR Endeavors with modern interiors, sold at prices between $249,000 and $285,000. The development, marketed as Osage Pine, includes rear decks, parking garages and high-end finishes. An online listing shows an available three-bedroom, three-bath home in the development selling for $289,900.

The saga that ended with the destruction of the 6200 block of Osage began with MOVE founder John Africa, a charismatic leader who attracted a number of followers with a revolutionary “back-to-nature” philosophy in the 1970s. The group eschewed electricity and modern medicine, residing in communal rowhouse complexes and staged frequent political protests. They also frequently drew the ire of immediate neighbors, who complained about trash piles, building code violations and provocative encounters with MOVE members.

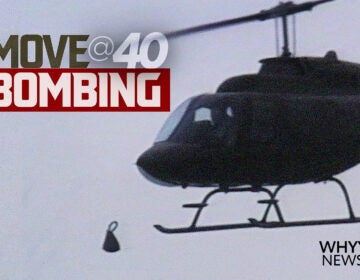

Police first sought to evict the group from a Powelton Village compound in the late 1970s, leading to a violent standoff that left an officer dead and many others injured. Years later, police again laid siege to a second MOVE compound after members clashed with neighbors — this time using explosives dropped via helicopter in an alleged attempt to dislodge the group.

The conflict and ensuing blaze, which critics say was intentionally allowed to spread, ultimately destroyed most of the surrounding blocks and left 11 MOVE members dead. (Former Mayor Wilson Goode, who led the city at the time of the bombing, recently called for present-day officials to issue a formal apology for the incident.)

Not long after the bombing, the PRA rebuilt rowhomes on the bombing site and invited displaced residents to return. But the redevelopment was tarnished by allegations of political dealing and the homes’ new occupants soon complained about plumbing problems, sagging ceilings and faulty electrical wiring.

After years of complaints, the city offered to buy back the homes in the early 2000s. Nearly two-thirds of neighbors accepted, those that remained received stipends for home repairs.

For years, the vacant homes looked set for demolition, until a report from the Army Corps of Engineers determined that most were salvageable. In 2016, after decades of vacancy and complaints from nearby neighbors, the PRA proposed a second redevelopment of the shuttered homes, without additional public subsidy: Offering the homes to developer AJR Endeavors for $1 apiece, to be resold at market value.

Gerald Renfro, a block captain on Osage Avenue, was one of about 25 neighbors who lived through the bombing and rejected the city’s early 2000s offer to move out altogether, accepting rehab money instead. He and others also later worked to bring the dilapidated state of the vacant houses on the block to the city’s attention.

Today, he says he feels vindicated for putting up with years of blight to stay in a section of the city he has always regarded as fundamentally good — a strong community, conveniently located near parkland, public transit, and shopping.

“Seeing the rehab, seeing them upgrade the homes, and to see our new neighbors moving in, it is uplifting to our spirits after living with the boarded-up homes for so long,” he said. “We feel that we neighbors who stuck it out accomplished some good for our community.”

Others, like Askia Bayyat, still remembered the last time the city had tried to restore the scarred block.

“I’m just going to watch and see what happens. In about 5 or 10 years they might be falling down, you’ll never know.”

West Philadelphia Councilmember Jamie Gauthier hailed the completion of this project, describing the failure of the initial redevelopment as adding “insult to injury for many of the residents of the neighborhood.”

However, she acknowledged that she had heard from some neighbors worried the new development would be successful — too successful.

“I know there are concerns about the projected sale price of these homes among neighbors. They are fearful that this will be a catalyst for gentrification and higher property assessments,” Gauthier said. “We do know from AJR that the vast majority of these homeowners are people of color, and a number of them benefited from the Philly First Homebuyer Program. Overall, it’s fantastic to see the community fabric being restored after all this time.”

The homes are reserved for sale to homeowners who intend to occupy them as primary residences, as per an agreement between AJR and the PRA.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.