Our historic preservation conundrum

Brantwood at Parkside

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Parkside – a neighborhood of old Victorian mansions that sits west of Fairmount Park – has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1983, but that gives little comfort to James L. Brown, executive director of the Parkside Historic Preservation Corporation.

Brown knows the real power to preserve the ornate 19th Century architecture lies with the Philadelphia Historic Commission’s local register, and Parkside submitted an application about a year and a half ago.

“It hasn’t received any attention,” Brown said. Some speculators have moved in, he said, “and they are doing no where near what these buildings deserve.” They would be held to high standards if the buildings were on the Philadelphia Historic Register, said Brown, who until recently served on the Historic Commission’s board as an appointee of the former mayor.

What Brown sees in Parkside underscores a lesson other local preservationists have also lately learned: Federal and state protection is limited. But the powerful Philadelphia Historic Commission can defend only what is listed on the local historic register – and currently has no staff member assigned to identify buildings or neighborhoods for the list. Its five-member staff is so strapped that even applications prepared by neighborhood groups sit for years.

“We are really limited not by the ordinance or rules, but by the staffing of the commission,” said Jonathan Farnham, director of the Philadelphia Historic Commission. “I rarely have the luxury of allowing one of our staff members” to research whether something is worthy of the Register.

Its five staff members handle about 3,500 cases requiring research and document preparation each year, Farnham said. The bulk of them – about 2,000 – result in recommendations that a federal agency may take or leave. These are related to projects for which the city will receive federal funds, and U.S. law requires the historic review, but does not require that the government to follow the recommendations.

If the Commission didn’t do the research for these projects, the city would have to hire a consultant, which would be much more expensive, Farnham said.

The Commission staff also does research and review for permit applications to alter the 13,000 properties already on the local Historic Register – about 1,500 annually.

The entire commission – the body appointed by the mayor – has 60 days to act on local permits. Within the first five days after an application is filed, the staff determines whether the full commission should consider the permit or if the application can be processed at the staff level, as 85 percent of them are, Farnham said.

With his limited staff, Farnham said, his office needs the help of city residents to find places worth preserving.

“The best way to protect a historic resource is to nominate it for designation before a developer or a public agency, SEPTA, or anyone, wants to demolish that resource,” Farnham said. “Usually people don’t make it public that they are going to demolish something that’s potentially historic until permits are in hand, so Philadelphians need to be proactive – to look around their neighborhoods and see what is worthy of protection before we get to that critical point.”

But Philadelphia Preservation Alliance Executive Director John Gallery said that in addition to Parkside’s historic district application, he knows of four others that have been waiting from 3 to 6 years for review: Spruce Hill and Overbrook Farms in West Philadelphia, a portion of East Falls, and a part of Germantown that surrounds the Awbury Arboretum. The nominating groups have spent, on average, $20,000 each, he said.

In 2007, the Commission added no new historic districts to the local register. It added one building to the list – a Victorian brownstone at 507 South Broad Street.

Brown and Gallery are both frustrated by the situation, but neither blames the Commission, which they say is doing the best it can with limited resources.

“I know why we are not receiving attention,” said Brown. “The Historic Commission is overwhelmed.”

“Right now, they are way beyond their capacity just to review the permits they are getting,” Gallery said. “They could not do more without more staff.”

Still, the situation is abhorrent to Gallery, especially in a city like Philadelphia.

“Why do people come here as tourists? To visit historic sites. What neighborhoods have the highest property values in the city? The historic ones,” he said.

“When National Geographic wrote its story about Philadelphia being the next great city, the next great destination, it said one of the reasons for people to come here is Philadelphia’s great architecture. The Philadelphia Historic Commission should be the model for the nation. It should be on the cutting edge of how to approach historic preservation. It should set the standards for the rest of the country. And we are far from that.”

PLICO demo

The Alliance has launched a postcard campaign to convince Mayor Michael Nutter and City Council to boost the Commission’s funding by $300,000. Nutter will introduce the new budget tomorrow.

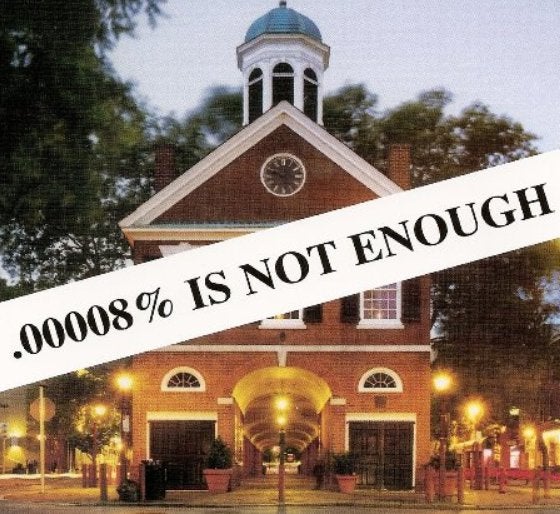

Gallery hopes many others will join the Alliance in inundating the mayor and council with postcards pleading their cause. The postcards say the Historical Commission’s funding is about .00008 percent of the total city budget – which is more than $3.5 billion – and that’s not enough.

This is the Alliance’s second go-round with postcard persuasion. Last year’s campaign didn’t work. “We’re trying again with the new mayor,” Gallery said. (Anyone who wants postcards can email Liz Blazevitch at liz@preservationalliance.com. The Alliance also hopes to have a downloadable postcard on its website by the end of the day.)

Gallery said $300,000 would pay for more staff, and that would not only shorten the waiting period, but allow the Commission to handle the additional permit requests they would receive if more historic properties were protected. If the historic districts in waiting were all approved, Gallery said, that would add more than 3,000 properties to the local register.

Farnham would not comment on the postcard campaign, beyond saying that it was Gallery’s right as a private citizen to lobby public officials.

However, he said a $300,000 budget boost would “satisfy current needs and bring the Commission closer to the national average for staffing at similar agencies in large U.S.

cities.”

When asked prior to the launch of the postcard campaign whether enough was being done to preserve the city’s history, Nutter said he knew that “because of staffing and funding” the Historical Commission is “backlogged.” Nutter said he ran up against the backlog as a councilman, when one of the neighborhoods he represented sought historic district status.

Preserving the city’s history is vitally important, and he’s behind that, Nutter said. “History is one of our great assets,” he said. It’s often what brings visitors to the city, and the old, walkable neighborhoods are “authentic” versions of what other cities are trying to fabricate.”

But in these tough financial times, Nutter said he did not know whether more money would be available for the Commission.

Parkside’s Brown worked for the city in the heady days of Edmund Bacon. He did historic research on sites, and then filed applications for federal Urban Renewal money. That plentiful money – which sometimes was used to pay for staff – made all the difference between then and now, he said.

“They are going to have to be creative if they are real serious and don’t have enough money to do it,” Brown said of the Commission. He suggested bringing on some planning interns from local universities, who could do some of the research that’s required.

Nutter said he wants to “raise the profile” of the Historic Commission, so that more people know they can nominate places important to them for protection.

Gallery and Farnham want community help, too. The Preservation Alliance has instructions for nominating a place on its website.

There are still many buildings and places that need protection, Gallery said.

The Philadelphia Historical Commission was created by ordinance in 1955. In the early days of the Register, there was a rush to add buildings and places, but “there was a tremendous focus on Center City and Colonial history,” Gallery said. “There were lots of buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries that were just overlooked.”

Gallery said the current list of preserved buildings is not only “heavily weighted” toward the Colonial period, but toward certain sections of the city. He has a map with little dots showing which buildings are on the local register. The dots are concentrated in Center City and Queen Village, with some also in West Philadelphia and up along Germantown Avenue. The rest of city has only a few widely scattered dots.

An Alliance review found that only 4 percent of the city’s buildings have ever been examined for historic significance, Gallery said.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

Race Street Firehouse demo

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.