Williams: ‘Dirty,’ ‘dangerous’ Philly needs new leadership

Calling Philadelphia a ‘dirty’ and ‘dangerous’ city, West Philly State Sen. Anthony Williams kicks off mayoral campaign against incumbent Mayor Jim Kenney.

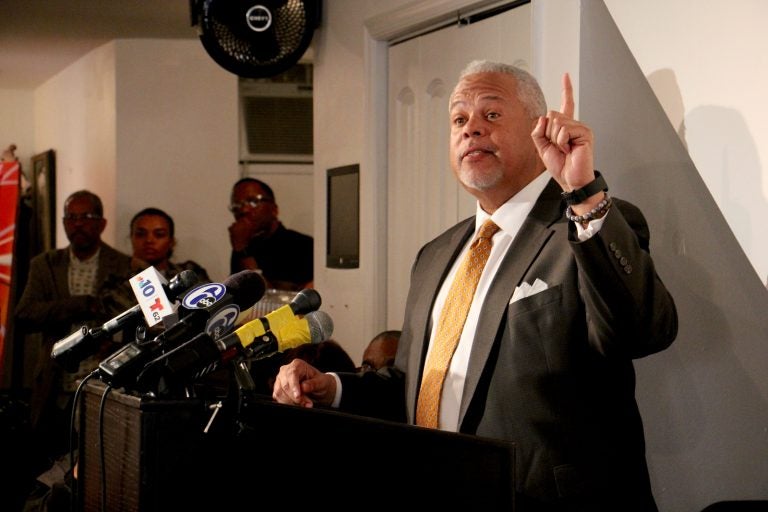

State Sen. Anthony Williams announces he will run for mayor of Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

State Sen. Anthony Williams began a campaign kick-off event in West Philadelphia Monday night by acknowledging that he’s entering the city’s mayoral race in an unusual way.

“In 30 years of public service, I have never, ever done anything like this,” he said, referring to his last-minute entry into the race with little money or political support.

He said he won’t have a war chest to compete with Mayor Jim Kenney, who defeated him in the Democratic primary four years ago.

“I don’t care if I have 10 cents in the bank,” Williams said. “I’m going to stand on 52nd Street, 60th Street, Northwest, South Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, Northeast Philadelphia, and we’re going to tell the truth.”

The truth, as he sees it, is that Philadelphia is “a dangerous city” and “a dirty city,” run by a mayor who’s failed to address persistent poverty, struggling schools, and property taxes driving longtime residents from gentrifying neighborhoods.

He denounced Kenney’s “crushing, regressive” tax on sweetened beverages.

Williams got some laughs when he said the tax is particularly unfair because it falls heavily on the poor, while affluent parents are allowed to benefit from the pre-K programs it funds.

“So if you had a latte tax, or a croissant tax, or an expensive cigar tax, I’ll take all those,” he said.

Williams said he would keep and expand pre-K programs, as well as Kenney’s Rebuild initiative to refurbish libraries, parks, and recreation centers without the soda tax.

He said that would require some “other revenue streams” and shifts in spending priorities he’s not yet able to specify.

Former City Controller Alan Butkovitz is the other candidate in the Democratic primary.

Kenney comes into the race with advantages of incumbency and cash. No mayor has failed to win re-election since the city charter was adopted nearly 70 years ago. Kenney’s campaign reported $508,000 on hand as of Jan. 1.

Williams’ mayoral campaign committee reported no contributions in 2018 and had just $15,000 on hand as of Jan. 1. Butkovitz reported $67,000 on hand.

Asking why, if he felt so strongly about the need for new leadership, he took so long to get into the race, Williams hesitated, then answered.

“I was fearful that I wasn’t, uh, going to be effective enough as a voice for those who feel disconnected from government,” Williams said, “and today, I’m not sure that I’m that person. I just know that there’s nobody running who wants to do that, so somebody has to stand up and do it, so I’m doing it.”

There is opposition to Kenney’s beverage tax and property tax assessments, and the mayor is running for re-election with an unwelcome association: By far, the largest Philadelphia supporter of his 2015 mayoral campaign, electricians’ union leader John Dougherty, is under federal indictment for allegedly stealing from his own members.

Williams reinforced that point Monday night.

“He’s involved with a guy who’s under indictment,” Williams said. “He has to own that.”

Williams has accepted more than $400,000 in contributions from Dougherty’s union in the past according to a Philadelphia Inquirer review of campaign-finance records. Williams has said he won’t accept any now.

Kenney hasn’t ruled out accepting help from the electricians and other unions, saying the contributions are from their members, not their leaders.

Williams has a history of launching campaigns for higher office that fail to meet expectations.

He began his 2015 campaign for mayor with plenty of backing from influential players, and he had the benefit of more than $7 million in spending from a Super PAC funded almost entirely by three wealthy financial executives committed to expanding charter schools.

Despite that effort, Williams got just 26 percent of the vote in the six-candidate Democratic primary, finishing about 30 points behind Kenney.

In 2010, Williams ran for governor, getting more than $3 million in contributions from charter school advocates. He got just 18 percent of the vote.

The one factor which could be a game-changer for Williams is an independent expenditure effort funded by the beverage industry, which wants to roll back the soda tax. There’s no indication at this point that they’re prepared to do that.

Asked about the prospect Monday night, Williams said that wasn’t in his plans, but that he’d be “appreciative” if it happened.

A spokesman for Kenney’s campaign released a statement saying, in part, that the mayor “continues to focus on ambitious plans aimed at addressing our biggest challenges, including the epidemic of violence.

“Despite his highly misleading criticisms about the Mayor’s record, Sen. Williams enters this race with even less support than he had four years ago.”

Butkovitz said in a brief telephone interview that he couldn’t predict how Williams’ entry into the race might affect his chances.

“I’d say, ‘Welcome to the race,’” Butkovitz said. “People have the right to a choice, and I think Sen. Williams and I will be highlighting a lot of similar failures of the Kenney administration.”

The primary election is May 21.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.