Temple exhibit shares the secret life of dolls

The Temple Contemporary gallery now has a solo exhibition by artist Trenton Doyle Hancock, who invited the Philadelphia Doll Museum into his invented universe.

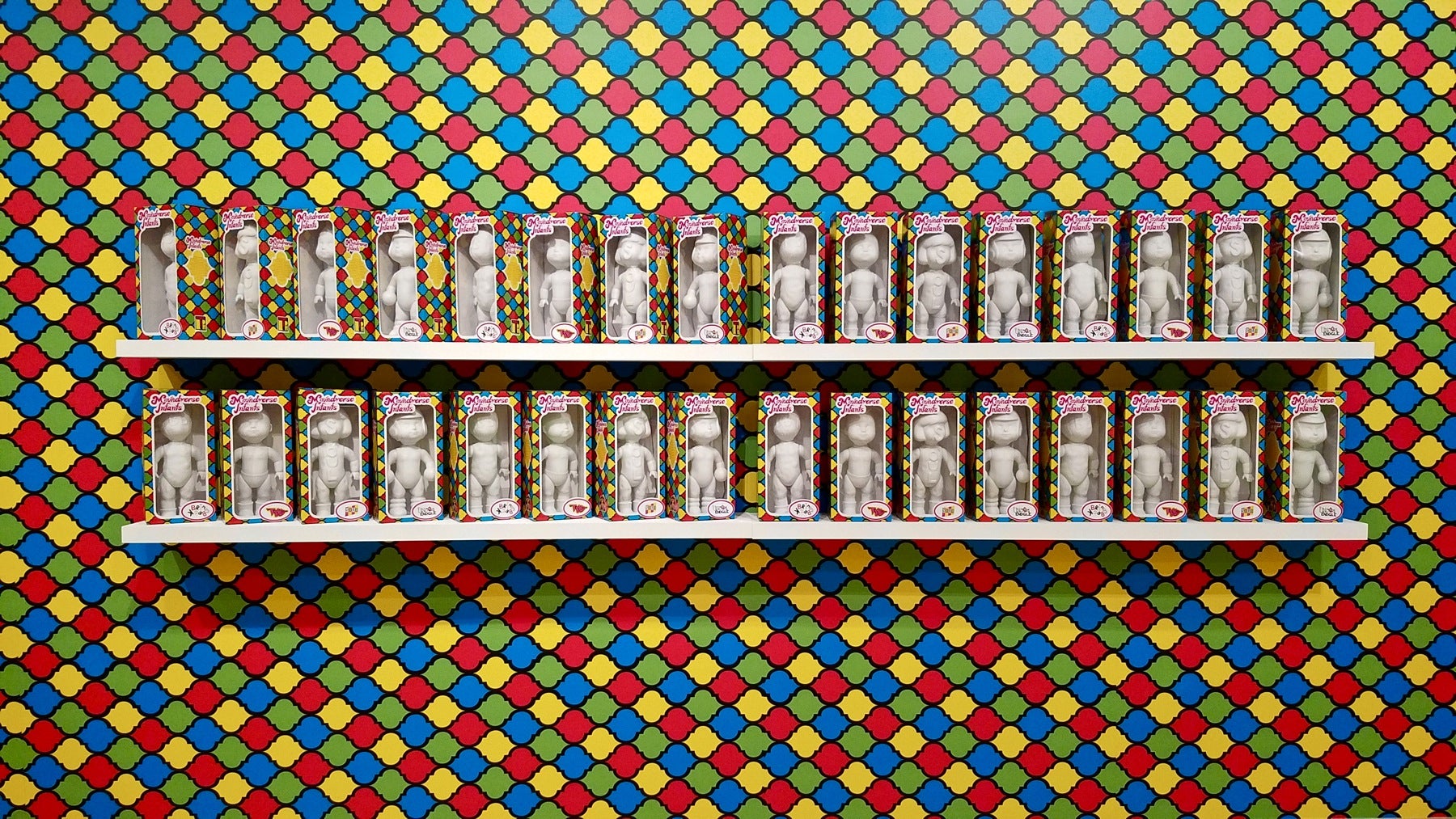

“Moundverse Infants,” an installation at Temple’s Tyler School of Art, combines the collections of artist Trenton Doyle Hancock and Philadelphia Doll Museum founder Barbara Whiteman. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

The art gallery at Temple University is now full of dolls.

Black dolls, white dolls, rag dolls, folk dolls, plastic dolls, German dolls, Italian dolls, naked dolls, dolls dressed in African kente cloth, boy dolls, dolls with pigtails that fly, dolls with electronic speakers in their tummies, a doll that comes with a bicycle, a doll that comes with a telephone, dolls that come with roller skates, a doll that comes dressed in a hospital gown which dissolves in water to reveal a packet of new clothes and the toddler doll’s gender.

There may be dolls you remember seeing as a kid — and dolls you have never seen before.

They all have two histories.

One is the real history of toy manufacturing and marketing. The Philadelphia Doll Museum is very good at telling that tale. Barbara Whiteman started it 25 years ago, collecting black dolls from around the world as a way to teach African-American history.

“I don’t have any dolls from my childhood, and I don’t have any dolls from my children’s childhood,” said Whiteman, who has collected more than 500 dolls. “I know the history of who made it, when it was made, what was going on in society when it was made. We know when black dolls became important in the doll market.”

In the 19th century, the American toy market was dominated by European manufacturers, according to Whiteman. Due to import restrictions around the time of the two World Wars, domestic production of dolls rose to meet demand. There were usually black versions of popular dolls (the first black Barbie was introduced in 1968), but often they were hard to find. It was not until the 1980s that the first mass-produced, mass-marketed black dolls emerged in the Huggy Bean line.

Dolls also have a secret history, the one imagined by a child while she – or he – plays with a doll.

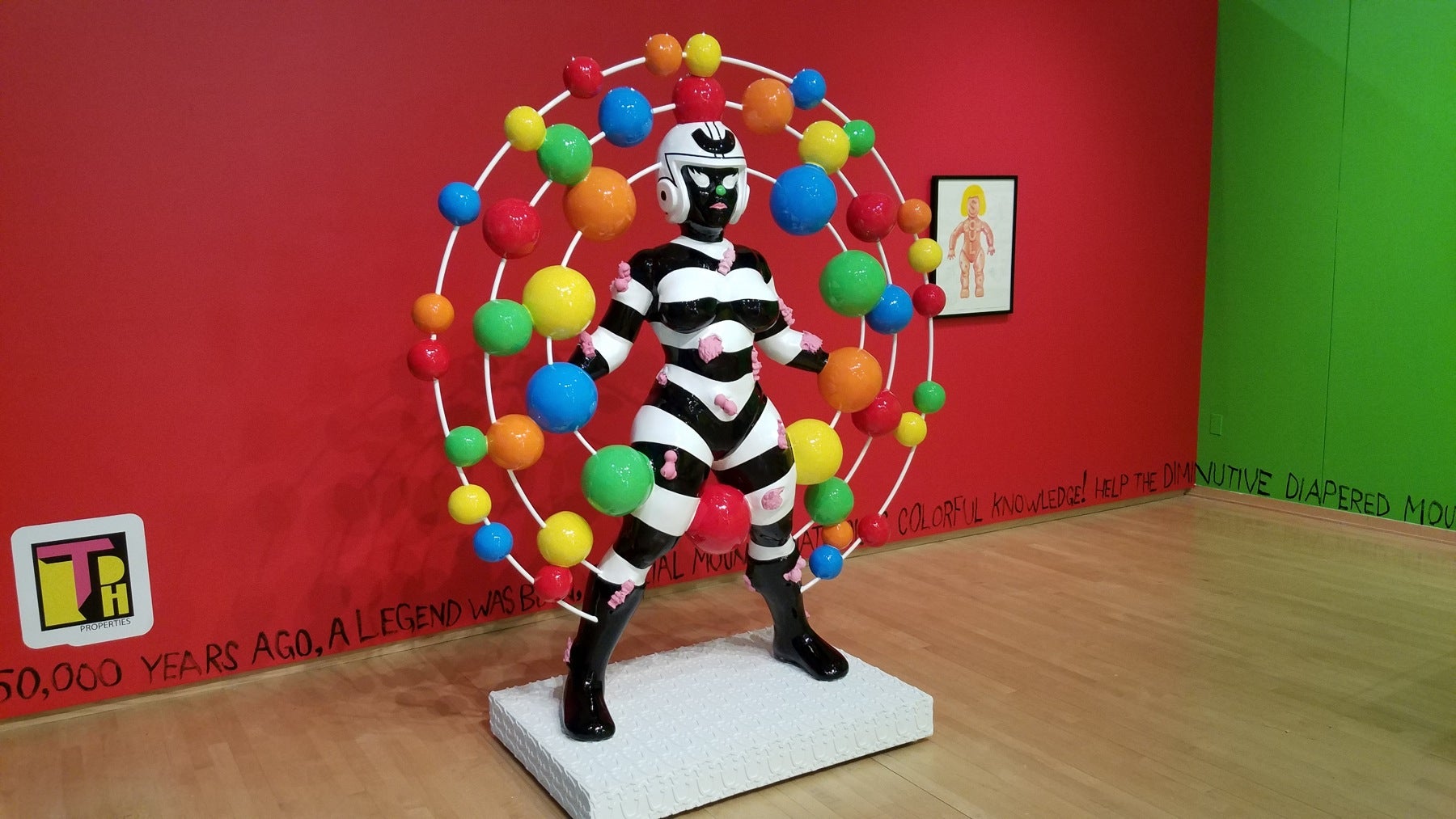

Over the course of his life, artist Trenton Doyle Hancock has invented a highly complicated set of characters inhabiting what he calls the Moundverse. His entire artistic output is involved — one way or another — in expanding, deepening, exploring, and illustrating the narratives of the Moundverse.

“For instance, Torpedo Boy, the character who has been with me the longest – I’m wearing his outfit right now – I invented him when I was 10 years old,” said Hancock during a recent visit to his alma mater, Temple University. “He’s been with me for 34 years.”

The Moundverse involves innocent creatures called Mounds – blobby, mostly featureless things that are troubled, but basically peaceful – who are beset by Vegans, skeletal and malevolent creatures that antagonize Mounds.

There are also a higher realm of creatures – including Torpedo Boy and Undom Endgle, a goddess wielding color as a weapon – who oversee the world of Mounds.

The Moundverse is partly autobiographical, and partly hallucinatory.

“A lot of it is doubling back on itself, the past mirroring the present, mirroring the future, mirroring other existences and realities,” said Hancock. “It’s this weird highway that goes down — and back up — in time.”

Hancock’s installation of “Moundverse Infants,” now on view at Temple’s Tyler School of Art, is split into two experiences. The first is a dizzyingly colorful, sparsely arranged room of Moundverse characters mass-produced as baby dolls. The Temple Contemporary gallery secured funding to help Hancock design and manufacture, in China, a line of dolls and packaging.

Stacked towers of cellophane and cardboard display boxes hold infant versions of four characters, all of them white. They are raw, unpainted production samples.

“As a toy collector, I get excited when I find unpainted samples,” said Hancock. “Sometimes I buy them direct from China. They are great to have in your collection, before paint and after paint.”

The other part of the exhibition is a collaborative installation of 144 dolls arranged in a grid on the wall. They are from the collections of Hancock and Whiteman, who have different approaches to collecting the same thing.

Hancock collects toys from the era of his childhood, i.e. the 1960s to the 1980s. As a “religious” regular at thrift stores, he grabs toys viscerally.

“At first it was Transformers, He-Man, G.I. Joe, things I had as a kid,” he said. “As I matured as a collector, it became more comprehensive. I wanted a clear idea of what was out there.”

On the other hand, Whiteman collects with the African diaspora in mind, seeking dolls she can use to explain African-American history to children, from handmade cornhusk dolls to the hugely popular Cabbage Patch Kids of the 1980s.

“I’m not acquiring anymore, but lots of people want to donate dolls,” she said, adding that she does not accept many donations. “But if we see something we do not have, it’s a welcome contribution.”

Whiteman’s dolls, on the left side of the wall, are all black. Hancock’s on the right are all white. Altogether they represent something about race in America.

“The first place people will go is, ‘This is like a toy store’…’Why are these dolls here?’…‘I had that one as a kid,’ ” said Hancocck. “I think there will be a lot of personal buttons first. Their guard is down a bit. Then people say, ‘Oh, the black dolls are on this side, and the white dolls are on this side.’”

Hancock was inspired by the Clark Experiment in the 1940s when young black children were shown white dolls and black dolls and asked how they felt about them. Most of the children identified white dolls as good and the black dolls as bad. The results were cited in the landmark 1954 case, Brown versus the Board of Education, in arguments against school segregation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.