Zebrafish are the new lab rats

At the University of Calgary scientists say this tiny, tropical fish may be a quicker, cheaper way to find new drugs to treat epilepsy.

Listen 5:34

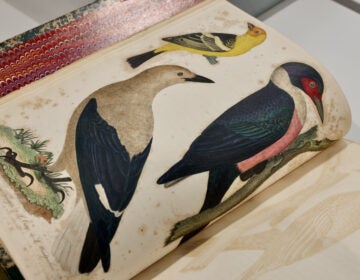

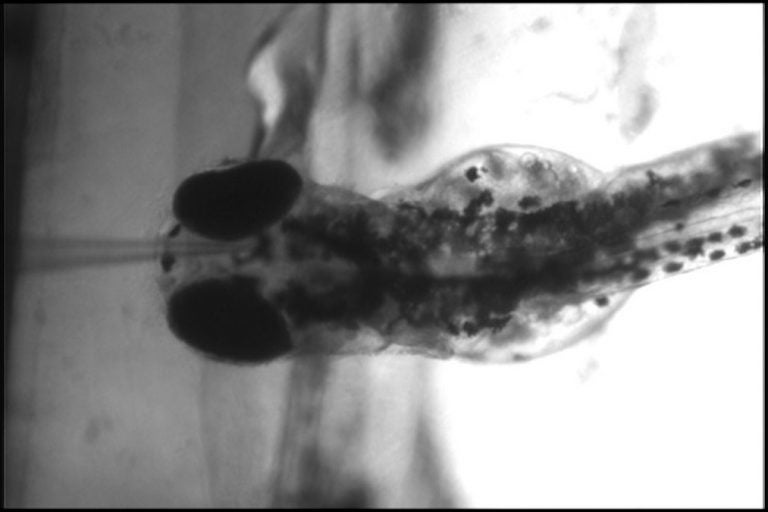

A zebrafish larva sits in agarose gel to stabilize it on a glass microscope slide. A microelectrode, which looks like a needle point, measures electricity in its brain, telling scientists how often and how severe its seizures are. (Dr. Deborah Kurrasch Lab, University of Calgary. l)

At the University of Calgary, scientists are using zebrafish in the lab in hopes of speeding up the drug discovery process. Neuroscientist Deborah Kurrasch and her team at the Cumming School of Medicine raise zebrafish to use in early phase research.

“You look at a zebrafish and you think it’s swimming around in water and it has nothing to do with humans, but in fact their brains develop very similar to humans,” Kurrasch says.

“They have a chambered heart, they have pumping blood, they have neurons and most organs that we would have in a human body.”

Researchers in her lab use libraries of medicines already approved to treat other conditions, then test those drugs on zebrafish. The scientists are hunting for therapies for neurological conditions such as childhood epilepsy.

The first step is using gene editing technology to modify zebrafish larvae to become epileptic. That happens when the fish are just days old, before they reach maturity.

“If you give me a lot of latitude they’re roughly equivalent to a child,” Kurrasch says.

She teamed up with neurologist Jong Rho, who runs a research lab at the University of Calgary’s medical school.

Kurrasch and Rho want to find drugs that work differently than the treatments that are available now for epilepsy. Most epilepsy medicines dampen communication between brain cells, resulting in fewer and less severe seizures. Still for about 30 percent of children, those medicines don’t work.

Rho and Kurrasch looked for drugs that would target the metabolism within each brain cell. Rho, who is in charge of pediatric neurology at the Alberta Children’s hospital, says each brain cell is like a city with its own energy grid.

“The city with the energy grid is functioning optimally,” said Rho. If the grid goes down, and there’s not stable energy, things start to fall apart — in a city and in our brain cells.

Rho and Kurrasch selected more than 900 already approved drugs to test.

The next step was to see how the genetically modified lab animals react to the medicine. This is the stage of research where mice and rodents are often used.

But zebrafish allowed the researchers to plow through their library of medicines more quickly. Fully grown, the fish are about 1.5 inches long, which means Kurrasch’s lab can store between 3,500 – 4,500 zebrafish at once. The fish can lay more than 200 eggs every week. So the scientists were able to breed and modify many zebrafish larvae for testing at once.

By contrast, mice need about three weeks to give birth, and they only have about eight to 10 babies at a time. Mice are more expensive to buy, plus they take up much more room to house.

After testing scores of drugs on modified zebrafish larvae, the team found a cancer drug called vorinostat worked to reduce the number and intensity of epilepsy seizures.

With that confirmation, the scientists only tested that one drug in mice; they’d already ruled out hundreds of other candidate medicines using zebrafish.

The screening phase went quickly, and the drug is already approved for human use. Now Kurrasch and Rho are set to start a trial in a group of kids with epilepsy.

“We’re actually beginning a clinical trial — that’s three years as opposed to 15 or more years,” says Rho. “So it’s a huge difference.”

In recent years, more medical researchers have been using zebrafish as a way to speed up the process before moving to rodents, he says.

“It is a trend and I think there are advantages,” Rho says. A trend that Kurrasch says is already moving into basic drug discovery.

“Pharmaceutical companies are looking around for alternative methods to find drugs and I think they are very closely watching zebrafish,” Kurrasch says.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.