With this Thanksgiving comes a sad first for many families: Lost loved ones

COVID-19 has taken hundreds of thousands of lives in the U.S. already, some very quickly. There will be mourning, and remembering

Listen 7:06

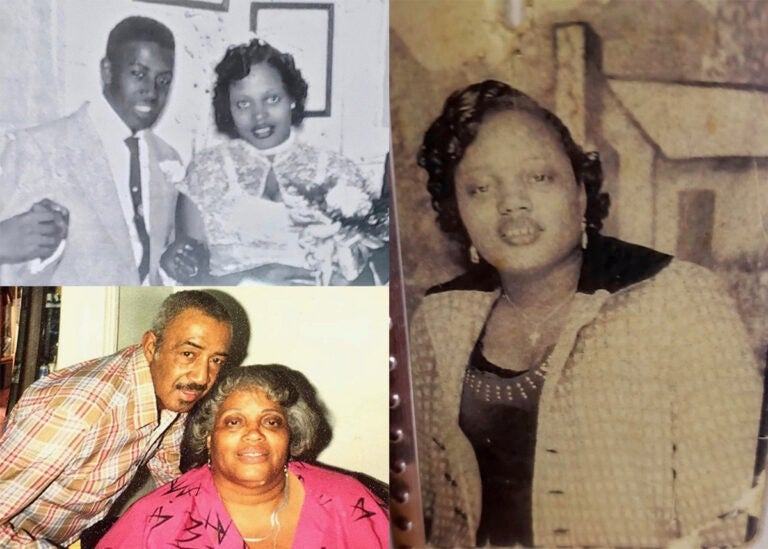

Ida (right, at 18 years old) was born in Martinsville, Va., and moved to Philadelphia when she was 3 years old. She married Johnny Robinson in November of 1956 (top left) and they raised six children. Johnny (pictured bottom left in 1989) died in 1997. (Courtesy of Diamond Franklin)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Ida Robinson loved to cook elaborate meals for almost every holiday, but Thanksgiving was her Super Bowl.

“The first of November, my mother would go shopping for food straight through to New Year’s,” said Ida’s daughter, Joann Robinson.

Ida would carefully plan every last detail involving Thanksgiving dinner. For her hummingbird cakes, she would cross state lines from her home in Philadelphia and pick up black walnuts in Virginia, her birthplace. Meanwhile, the components for Ida’s custom charcuterie plates required a trip to Philly’s Reading Terminal Market. The ingredients for the holiday fruitcakes would need to be soaked for eight weeks, so that required some work in October. The list went on.

Even after Ida started living in a long-term care facility several years ago, family members, including Joann, continued her traditions. The whole family would go visit Ida with armloads of food.

This year will be the first Thanksgiving the family won’t get to be with Ida. She died in April at age 84 from complications of the coronavirus.

For thousands in the United States, this Thanksgiving holiday will be the first without a loved one — as of Nov. 16, almost 250,000 Americans have died as a result of the virus. And the pandemic is changing how people grieve: Saying goodbye and mourning as a community have been restricted and will stay that way at least for several more months as COVID-19 continues to ravage the country.

For Joann Robinson, grieving her mother has been complicated. Joann didn’t get to perform some of the rituals that come with losing a loved one. For example, coronavirus concerns prevented her from saying a final goodbye to her mother in the hospital like other members of the family. But Joann said perhaps that was for the best.

“At the last few moments, she was taken off of everything and just was laying in a bed with just her face showing,” Joann said relatives told her. “She was sedated. She didn’t know anyone was in the room. She couldn’t move, couldn’t talk, couldn’t open her eyes or anything.”

She had to experience her mother’s last farewell secondhand, through relatives who walked her through Ida’s final moments and showed her photos. Even if Ida had been awake, Joann tells herself it’s unlikely she would have recognized the loved ones at her bedside — they were covered head to toe in personal protective equipment.

Joann said she prefers to tap into the well of good memories she has of her mother and keep an upbeat attitude.

Still every now and then, she does something that brings her to tears but also brings some sort of comfort.

Joann will play some of the final voicemails Ida left on the answering machine before getting sick. Ida was in her long-term care facility at the time and checking in. Joann and her daughter Diamond Franklin laugh at how Ida would always punctuate her message with her full name, as if the family would be unable to recognize her voice.

The voicemails make Joann feel close to her mother, but they also harken back to Ida’s final months.

“What aches is when we would talk to her on the phone, she wanted to know why weren’t we there?” remembered Joann. “It was hard to tell her and have her understand that they’re not letting us come to the facility.”

Joann, her daughter Diamond, and the rest of Ida’s family are trying to figure out what grief looks like for them because, as with so many things during the pandemic, it looks different this year.

Diamond said she and her mom can’t lean on family or church the way they typically would in trying times.

“During a time of grief, you usually seek to come together more,” Diamond said. “You seek that and to embrace one another. And it’s difficult going through the loss of a loved one at a time where everyone is unfortunately forced to be apart.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

‘Grief on steroids’

Kathleen O’Hara, a psychotherapist who helps mourning families across the globe, said grieving a loved one who died because of the coronavirus is different — the death comes with an added trauma component.

“This is grief on steroids,” she said. “There is fear around the disease itself, how it could have happened. There’s the fear of the unknown. There’s also the quickness of it: No warning, things like that. So it’s grief, but there’s a trauma component to it.”

O’Hara is no stranger to traumatic grief herself — her son Aaron was murdered in 1999, when he was 20 years old. But she said that even when faced with extreme hardship and unbearable grief, human beings are adaptable.

Thanksgiving and the winter holidays present an opportunity to find new ways to mourn, she said. Sharing stories, creating videos in the loved one’s memory, laughing, crying, or simply giving thanks for the time you had with the loved one are a few ways to mourn in person or virtually.

The important thing, according to O’Hara, is to understand that while people can’t change how the pandemic barred them from saying their final goodbyes or going to funeral services, there are other ways to move forward, even if it seems impossible to grieving families right now.

She has words that might not sound very comforting but are meant to be: This too shall pass.

“Your grief is real and true, and it has to be gone through,” she said. “There’s no way around it … you know, cry, yell, scream, and then know that this will pass and create the new rituals that will make your loved one closer to you.”

Right before Ida Robinson’s nursing home went on lockdown, Joann Robinson and daughter Diamond Franklin took Ida for a big birthday celebration.

“Her birthday was February the 29th, she was a leap year baby,” said Joann. “She actually got a chance to have a birthday on her birthday, and we celebrated three weeks in a row.”

Joann said she tries to remember all the restaurants the family took Ida to and all the favorite foods she was able to make for her mom, including a rich chocolate cake Ida loved, as well as a homemade iced tea. These are the moments Joann tries to hold onto, not the images of her mom hooked up to a ventilator in a hospital.

And even though the pandemic limits the size of this year’s Thanksgiving feast, Joann and her daughter want to honor Ida’s memory by making the food she used to love. They won’t be going to Philadelphia’s famous Reading Terminal Market to get cured meats or across state lines to get black walnuts.

But Joann and Diamond will attempt to make one of Ida’s famous baked treats for the first time: a pineapple cake with coconut flakes and icing. Also on the menu is a sweet potato pie with a hint of pineapple juice, Ida’s secret ingredient.

“I myself am not as skilled a cook as my mother and my grandmother,” Diamond said. “But I do like to help and just watch and witness because I feel like I’m almost seeing my grandmother cooking through my mother.”

Joann knows she might still long for her mother. If that happens, she might play one of Ida’s final messages to the family.

One of them asks the family to give Ida a call when they get a chance and it ends like most of Ida’s messages.

“Talk to you later. This is Ida Robinson. Bye-bye.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)