When togetherness means home is no safe haven

COVID-19 has ripped through communities with high rates of household crowding. An inside look into how the virus spreads in cramped multigenerational homes.

Listen 19:27

COVID-19 has ripped through communities with high rates of household crowding. Ana Cordero and her family felt that firsthand. An inside look into how the virus spreads in cramped multigenerational homes. Ana (left) as a young girl (at 6 years old) with her family at The Bronx Zoo. (Courtesy of Ana Cordero)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

We’ve all heard the term by now: multigenerational housing. It’s one of the big factors that gets mentioned in connection with the spread of the coronavirus, and it happens to be a topic that I am very familiar with.

When my parents, my sister, and I first came to the United States in 2002, the four of us went from living in a one-story house in the port city of Manta, Ecuador, to living in the basement apartment of my aunt’s house in East Elmhurst, Queens. The four of us shared that apartment with my grandmother, a different aunt, her husband at the time, and my soon-to-be-born cousin. And if that weren’t enough Lopezes in one household, the aunt who owned the house lived upstairs with her son and her brother, my saloon-singing uncle, who would use the basement boiler room as his “studio.”

The basement itself was pretty small: It had two bedrooms, one for the four of us — my immediate family — and one for my aunt and her immediate family. My grandmother slept in the living room area, on a bed that was separated from the rest of the space by a curtain. A small attempt at privacy in a not so private place.

This is what crowded multigenerational housing looks like. Eight people sharing a very small space.

The make-up of that apartment changed over time as different family members moved in and out of the basement. When I was in high school, my parents, sister, and I moved out as well, to a two-bedroom apartment in Corona, Queens.

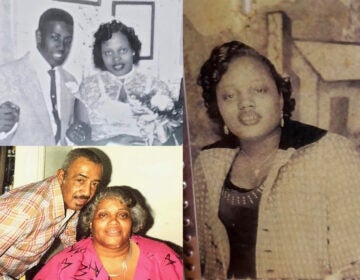

The Corderos

Growing up like this can feel kind of odd. I didn’t really think about it much in my adult life until Queens became a major hot spot for the coronavirus and health officials started telling people to stay at home.

I reached out to some people and I heard from Ana Cordero, she’s a friend of a friend from back in Queens. We quickly bonded over being from Ecuador, having lived in a relative’s basement, and feeling embarrassed about it.

“I had to decide which friends I could trust in order to be, like, `Hey, come over and let me show you the way that we live.’ And I would find myself apologizing for the living situation.”

It wasn’t hard finding someone else who has lived this way, especially in New York City, where as of 2011 Hispanics were one of the two groups with the highest household-crowding rates, 23.2%.

Ana told me about the first time she felt shame about living this way. She was in the third grade, working on a science project about plants with her friend.

“I remember we were trying to decide whose house we should go over so that we can do this project,” Ana said. “And she was talking about how, ‘Oh, I can put the plants here in my backyard and my mom can make us snacks. And when we’re not doing the project, we can play on my trampoline.’ And I was like, girl, you have a trampoline? And I was just going to tell her like, ‘Hey, I have this window in the kitchen where we can keep the plants.’”

When Ana’s family first got to the U.S., they lived with her great-aunt, Tia Olgita. After a few years, they moved out on their own. But their family splintered — Ana’s father was very abusive toward her mother.

“I remember at the worst, I believe my dad was choking my mom outside in front of the neighbors, and the police came,” Ana said. “And I think that was the last incident that we had before we went to the shelter.”

They stayed in the shelter for a while, then bounced around — spending some time back with Tia Olgita, and after that in a rundown two-bedroom with a bedbug infestation.

Ana’s mom tried to find a place that was within their price range, but it was just impossible in an ever-gentrifying New York. She applied to public housing when they were first living in the shelter, but they didn’t hear back for seven years, and by the time they did, they didn’t qualify for low-income housing anymore. Six years ago, they finally found a one bedroom apartment.

First, it was just Ana, her brothers Luis and Diego, and their mom, who is also named Ana. But soon, the family grew. Diego’s girlfriend, Adamary, also moved in, and they had two kids, Elijah and Journey.

Three generations under the same roof, again.

“My mother, Ana, myself, and my brother Luis get the living room, which is the bigger space. And we divide that living room into different sections so that we each get our own space.”

Ana said those “spaces” were mostly for sleeping: She and her brother get their own beds, and their mom sleeps on a reclining couch.

“Then you head over, down the hall to the actual bedroom, and that’s where Diego shares a space with his girlfriend, Adamary, and the two babies.”

Altogether, the seven of them shared around 700 square feet.

Though living in those cramped quarters made their situation stressful at times, there were a lot of good aspects, too.

Bringing the family together

In my family’s case, although there were many of us living in the basement, it was mostly working adults that split the rent, bills, and money for food. It was cheaper for everyone.

Because my grandmother was at home, my parents didn’t have to worry about me and my sister. She would cook dinner and take care of us, and we would take care of her. It was a symbiotic relationship.

We would also spend a lot of time together. We’d gather around on the couch and watch TV, “Sabado Gigante” and old Mexican movies on Univision and Telemundo. On the weekends, other family members would come and visit us.

The basement was also filled with music all of the time. From my uncle in his boiler room studio rehearsing “las corta venas,” those classic depressing love songs that older Latinos listen to while they drink, to the salsa music that my parents loved so much, it really built in a soundtrack to that time in my life.

For Ana Cordero’s family, it brought them closer together — when the family wasn’t arguing.

Although her childhood was filled with traumatic experiences, when her brother Diego fell in love with Adamary and they had the kids, it was a ray of sunshine for the family.

“The abuse that we all faced together kind of tore us apart,” Ana said. “And so my brother having children really gave us a reason to come together for a common cause, [which] is that we all love these children.”

With new life came hope for a happier future.

“I think that’s the brightest thing that’s out of all of this,” she said. “To have the opportunity to see my niece and my nephew frequently and to take care of them really feels like a privilege. I love being able to play a role in their lives, and I really don’t see that happening the way it is happening if we weren’t able to be in such close quarters with each other.”

Living with your whole family can certainly bring you moments of joy, but when everyone is living in a cramped space, it can also pose some serious health risks, especially now with the coronavirus.

Home is where the danger is

In March, people were asked to shelter in place to flatten the curve and reduce the risk of infection. We all heard the stay-at-home orders from elected officials and public service announcements from celebrities.

But for families like Ana’s and mine, those orders put them at a higher risk.

“When my mom got sick, we did not have the same opportunities to isolate the way we would have wanted,” Ana said.

The illness in Ana’s family started with her great-aunt, Tia Olgita — the one who took them in when they first came to the U.S. and when they were experiencing homelessness. Olgita started displaying symptoms in late February.

“She had been telling my mom that she had been feeling sick and … she was just anticipating like a yearly flu that she gets.”

Ana’s mom took Tia Olgita to the hospital for the first time at the end of February, and initially she was misdiagnosed. Remember, this was at the beginning of the pandemic, when doctors didn’t know much about how to treat the virus. And, just as troubling, there was little capacity to test for it.

“Her second hospital visit was in the second week of March,” Ana said. “And mind you, my mom is being a caregiver throughout this time whenever she can on her days off. So at this point, my mom doesn’t have any actual days off. She’s either working or taking care of my aunt.”

After the second hospital visit, her aunt was given some antibiotics for pneumonia. Less than two weeks later, she was back in the hospital and she was finally tested for COVID-19, but by then it was too late.

“The doctor said that she had 50% lung function at that point, and she got intubated,” Ana said. “They had a talk about how … they would let us know how she would progress throughout the night. And then at some point throughout the night, they called my mom to tell her that she had passed.”

After about a month of trying to get some type of care, Tia Olgita had died. Then the family got more bad news.

“And we got a call from the hospital saying that they had the test results, and they told us that it came up positive. And so we were just asking like, ‘Why are you telling us this right now?’ And then that’s when they realized that she had already passed in the hospital that they were calling from.”

The test confirmed what the family had feared all along, that Tia Olgita had been sick with COVID-19 the whole time. Ana’s mom had been around her aunt a lot, and later that same day she started displaying symptoms herself.

She had a sore throat, headaches, was feeling really fatigued and could not get up. Ana went to stay with her boyfriend, Eric, and his family.

“Because at that point, I didn’t feel safe in the apartment with so many people. And that was the last time I got to see my mom for a few months.”

The thought of being in that small apartment without any space seemed scary, it seemed like if she stayed — she would inevitably get sick.

And that’s exactly what happened with the rest of the family. At first, it was just her mother, who got really sick.

“We got very scared at certain points, and we didn’t feel safe enough to go to a hospital because it was just from our belief in what we were seeing on the news, and what we had already experienced, that my mom would just be intubated and that she wouldn’t come home again.”

Ana’s mom would have uncontrollable shivers no matter how hot they tried to make the room. There were times when the nausea was so bad that she just wouldn’t eat for days. Once they got a hold of one symptom, another one would hit differently, it was like playing whack-a-mole with coronavirus traits.

“It was just like a plethora of different symptoms that could hit you,” Ana said. “And each one lasts several days until that symptom ends and then another symptom begins, and you get better and then you get worse. That’s what we witnessed for my mom. My brother just needed to rest for a few days. And then the babies got sick.”

The virus jumped from Ana’s mom, to her brother Luis, then to the babies. Once it got to the babies, the rest of the family got sick, though no one as bad as Ana’s mom.

Back in March, my family got sick as well, for the same reasons. My parents and my sister are still living in that same apartment we moved to in Corona, but now they’re living with my maternal grandmother as well.

And the apartment is very small. When you walk in, you’re immediately in the kitchen. There’s a bathroom through a door to the right, and the other half of the area is occupied by my parents’ bed on one side and a TV and couch on the other. Then two doors lead to the bedrooms — my sister’s and my grandmother’s, the only rooms in the whole apartment with windows.

In a place like that, keeping your distance or quarantining is impossible. Everybody is breathing in the same air in the same small space, walking past one another constantly.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Crowded housing as a factor of disease spreading

Data from New York shows that the spread of COVID-19 in crowded living situations was very common.

“We found that COVID positive test rates were higher in neighborhoods with more household crowding,” said Ingrid Gould Ellen, a professor at NYU’s Wagner School of Public Service and the director of the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy.

The Furman Center put together a neighborhood analysis that broke down some of the disparities in COVID-19 incidence across neighborhoods.

“Maybe somewhat surprisingly, we did not find that positive test rates were correlated with higher density,” Ellen said.

New York City is densely populated, but there are different kinds of density — density within apartments, and neighborhood density.

“Some of the … highest-density neighborhoods in New York, where people live in tall apartment buildings, had some of the lowest rates of positive test cases.”

These are affluent areas like Manhattan, where high-rises can house thousands of people in one building. In those places, people have their own separate spaces, their own kitchens and bathrooms, despite living on top of one another, so to speak.

The relative safety of those areas is ironic, given that they are the very neighborhoods that people fled in droves at the beginning of the pandemic.

Ellen said the neighborhoods that were the hardest hit were the ones where the share of the population is predominantly Black and Latino, two of the top three racial groups living in crowded multigenerational homes.

Another finding of the analysis was that low educational attainment also correlated with areas that saw high upticks of COVID-19 infection.

“In neighborhoods that had lower shares of adults with college degrees, we saw higher positive test rates,” Ellen said. “And we believe that’s because … the workers without college degrees are more likely to be essential workers, to be workers who can’t do their jobs remotely and safely shelter in place.”

Essential workers — people working service jobs, janitorial, and medical staff — are not able to work from home, which means more contact with people, increasing their chances of infection.

A simple message can be too simple

Holly Taylor, a bioethicist at the National Institutes of Health, said messaging is very important.

“When we say something like, ‘Everybody should stay home,’ for the vast majority of people, that means, ‘OK, I’m going to stay home. I’m going to figure out how I can telework, if not, how on earth am I gonna get my job done? Am I to lose my job? What does that really mean?’ Or, ‘OK, I’m going to stay at home, but I live with a lot of different people and they all have jobs that take them out of the home, and how am I going to actually stay at home and protect myself from risk?’ Right? It’s not as easy as well, just stay at home.”

Taylor said the stay-at-home orders and the PSAs didn’t fully take into account people living in multigenerational homes, and the dangers they might be exposed to.

“I don’t know what Governor [Andrew] Cuomo was thinking, but this is often a challenge that we encounter in public health ethics generally.”

Coming up with just the right messaging can be very hard for public health experts, she said. And when you’re in the thick of it, in an actual emergency, it can be even harder.

“One of the things that’s often on that list is to make sure that your messages are accurate and actionable,” she said. “But then when you’re actually in it, and you know, that quote unquote, the most efficient way to reduce spread is for people to not be on the street, right? Not be outside, not be congregating, a message like ‘stay at home’ is, on one hand, very simple. And on the other hand, just too simple.”

Quarantine hotels

Telling people to stay at home wasn’t going to be enough.

As an alternative, the city began offering a hotel program in June for anyone who tested positive for COVID-19 and their close contacts to stay. It provides resources needed to safely separate from family members or from roommates.

“New York City realized early on in its experience with the pandemic that given the number of cases that we were seeing, and given the types of housing stock and the types of living situations, that our residents find themselves in, other places to isolate and quarantine were going to be necessary,” said Amanda Katherine Johnson, assistant vice president in the office of ambulatory care for New York City Health and Hospitals and director of the city’s Take Care program.

The program is part of the Test & Trace Corps and residents can stay at the quarantine hotels free of charge.

“When they come to the hotel program, they’ll get three meals a day, plus there’s snacks. There’s Wi-Fi, a comfortable bed, a private bathroom. There are clinical supports on site. So we do have nurses and different levels of nursing assistants who can do things like monitor your temperature, monitor your oxygen saturation … just making sure that you are safe to stay in the community and to expedite your escalation to a higher level of care if you need it.”

Once a person calls the program, that person is offered a ride to a quarantine hotel, where staff takes a temperature reading and performs an intake. The program usually takes over an entire hotel. There are different floors for people who have tested positive, and for people who are suspected to have COVID-19, and categories in between.

The Take Care program also offers other types of support, to connect people who are isolating or quarantining at home with community based organizations and other resources to get the help they may need.

“This includes … making sure that people have food delivered to their doorstep during the time that they’re isolating or quarantining. And then another concern that people have, not surprisingly, is just their financial well-being. So to connect people with paid sick leave … rental advocacy, utilities, medication delivery, really trying to figure out what are going to be the things that get in the way of them being able to safely separate for the full duration and seeing how we can intervene on that.”

So far, the program has housed over 3,500 people at quarantine hotels.

Though the hotel program was initially started as a way to reduce the pressure that hospitals were feeling — by offering an alternative place for people to quarantine, Johnson understands that this service is necessary for people who can’t quarantine safely because of household crowding, and, as the Furman Center’s Ingrid Gould Ellen said, those who cannot work from home.

“I think the other [thing] we just have to keep in mind [about people living in this type of] housing stock is that it’s going to track with a lot of other characteristics, the type of jobs that people have and the risks that they’re exposed to when they have to go to work. And they don’t have the option of working from home, but also compound their risk of contracting COVID and the risk of transmitting it to a loved one in the household.”

Recovery

My family tried to stay at home, but both my parents have jobs that don’t allow them to work remotely. My dad is a handyman, and my mom is a home health aide. My mom was actually furloughed for a while and had to apply for unemployment during the time she was sick. My dad worked through his sickness, even though he shouldn’t have. But he just couldn’t afford to take time off from work.

Everyone in my family, thankfully, recovered.

Ana Cordero’s family is doing a lot better now as well, they were all able to recover, although her mother is still not the same.

“The situation with my mom is just her dealing with fatigue,” Ana said. “But her fatigue is nowhere near as bad as it used to be … so yeah, everyone’s doing a lot better now.”

After living with her boyfriend’s family for a while, Ana and Eric decided to move out on their own and are currently living in a three-bedroom apartment with two of Eric’s cousins — one of whom they took in after she was faced with a situation that left her homeless — an experience Ana could relate to.

And although the past few months have been a whirlwind of emotions, she feels like she’s finally made peace with everything that’s happened.

“I definitely do find myself thinking more about it, but I feel calm. I feel a sense of closure now,” Ana said. “The fact that I can help Eric’s cousin overcome this obstacle that’s in her life, where she could very well be in what could be the lowest point in her life. This could be the lowest point in her life, so far. And me being here being able to help her, it brings me a lot of joy to be able to play that role in her life at the moment because … I really would have needed it. I really would have loved for someone to be able to do this for me.”

Support for WHYY’s coverage on health equity issues comes from the Commonwealth Fund.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)