Treating tremors through ultrasound waves deep in the brain

A new non-invasive procedure uses a beam of ultrasound waves to damage brain tissue associated with the involuntary movements.

Listen 3:29

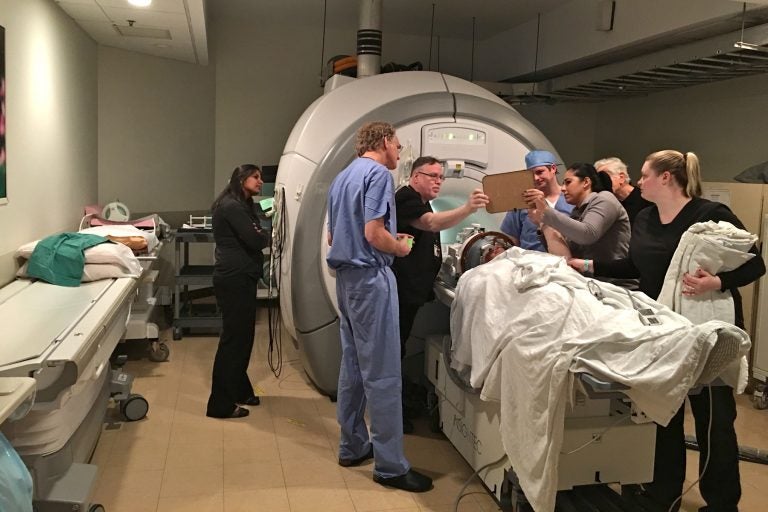

Dr. Gordon Baltuch and his team check on James Neyhart throughout a procedure that uses a beam of ultrasound waves to stop his hand from trembling. (Kyrie Greenberg/WHYY)

James Neyhart, a Vietnam veteran who lost his right arm in combat, started noticing a tremor in his left hand 15 years ago.

He is one of millions of Americans who have essential tremor, a condition that causes a person’s hands to shake uncontrollably while using fine-motor skills such as writing or eating. Otherwise, they’re healthy.

Over time, Neyhart noticed his condition getting worse.

“I can’t write any longer, I can’t sign my name. It is very annoying because it limits everything you do,” explained Neyhart.

After trying every medication for his condition with no luck, he was told by doctors that the only other option was deep brain stimulation — a procedure that inserts a wire attached to a pacemaker into the brain, which suppresses the tremor. His wife, Judy, didn’t like the sound of it.

“We said ‘no,’ we’re not going to do that yet because there were too many — ‘this can happen, that can happen, that can happen,’ ” she said.

Instead, Neyhart signed up for a new non-invasive procedure that uses a beam of ultrasound waves to injure a region of the thalamus — a tiny part of the inner brain that relays motor and sensory signals to the cerebral cortex — to stop the involuntary movements.

He was Pennsylvania Hospital’s seventh patient to undergo the procedure approved by the FDA last year.

“I found out about it in a magazine ad,” said Neyhart, who subscribes to publications that focus on essential tremor.

This month, after Neyhart’s head was shaved and he was given a mild anesthetic, Dr. Gordon Baltuch did a series of CT and MRI scans to identify the right spot in Neyhart’s brain.

“There’s a lot of calibration,” explained Baltuch, as he oversaw two computer screens with images of Neyhart’s brain. Using a low, test dose of ultrasound, “we shot where we thought was the center, but we were a little bit off to the right, and we took our eyepiece and we shift our eyepiece just a little bit,” he said.

As Baltuch dialed in on his target, he intensified the strength of the ultrasound pulse, all while making sure the beam wasn’t too hot.

“One person’s brain is not like the other,” said Baltuch. “If you want to see it in a very simplistic fashion, if you put a heating coil within an egg, some eggs are going to become boiled at much different temperatures and in a different way depending on your egg.

“So if you go in and you just do one temperature — some will be undercooked, some will be overcooked,” he continued.

To help prevent overheating, Neyhart wore a rubbery hat filled with cold water in a 60-degree room. And in order to make sure everything was going well, he was awake the whole time.

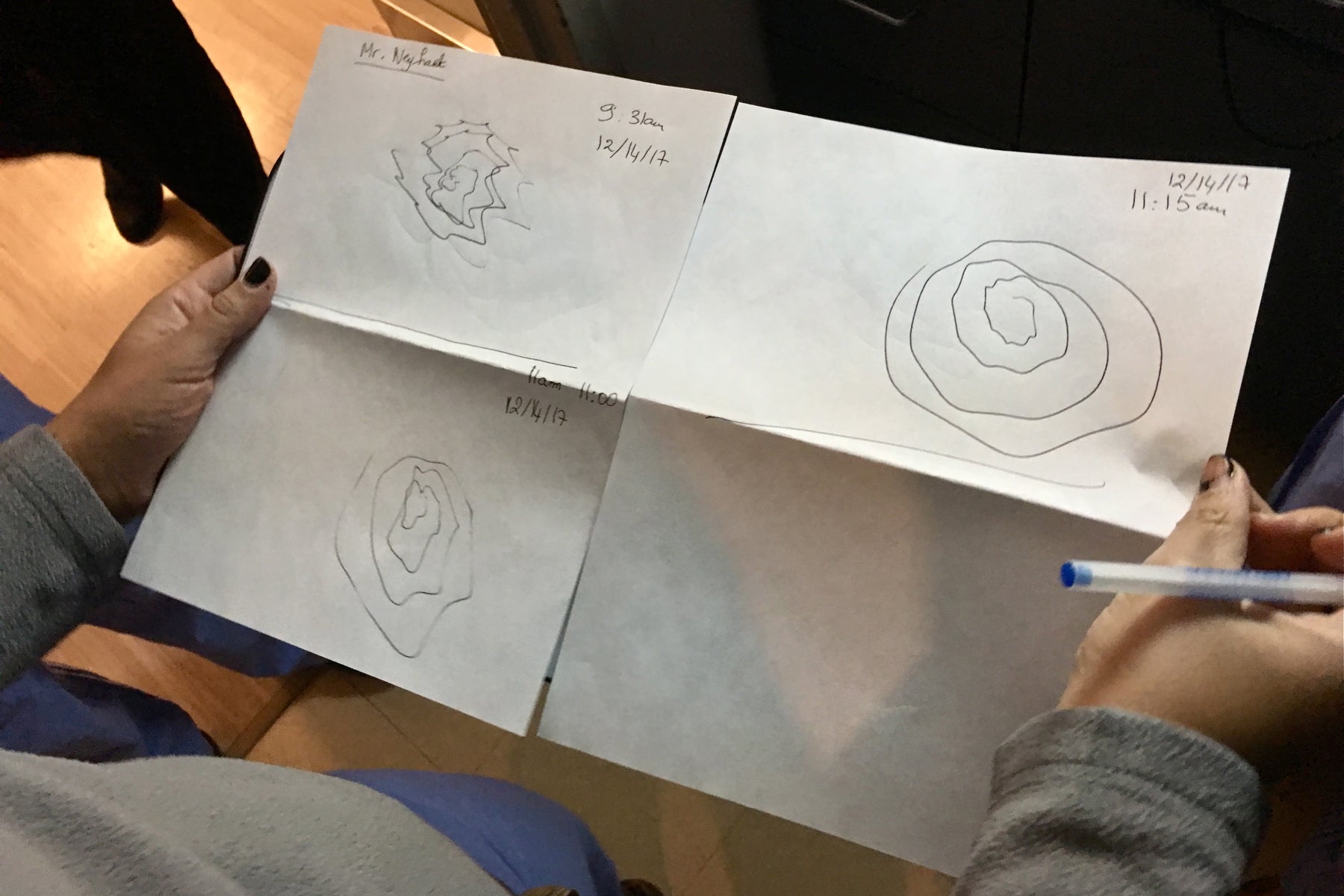

After each zap of ultrasound, nurses checked his tremor by having him draw a spiral on a sheet of paper. Even with the smaller doses, his hand became noticeably steadier.

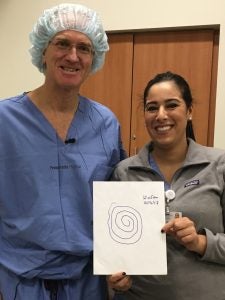

The final zap made Neyhart feel dizzy. But less than five minutes later, he drew a nearly perfect spiral — something he hasn’t been able to do in years. As he was wheeled to the recovery room, Neyhart waved as nurse practitioner Hanane Chaibainou proudly held his drawing.

“Every time I start getting all emotional — I mean can you believe how he was just two hours ago? It’s just unbelievable.” she said.

According to the FDA, essential tremor ultrasound patients generally see a 40 percent improvement in their symptoms after 12 months. Some people, though, reported recurring numbness in their fingers, headaches and trouble balancing after the procedure.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.