Should we talk about science like it’s magic?

We struggled to balance information and entertainment back in science TV shows to the '50s and '60s. In some ways, we still do.

Listen 7:47

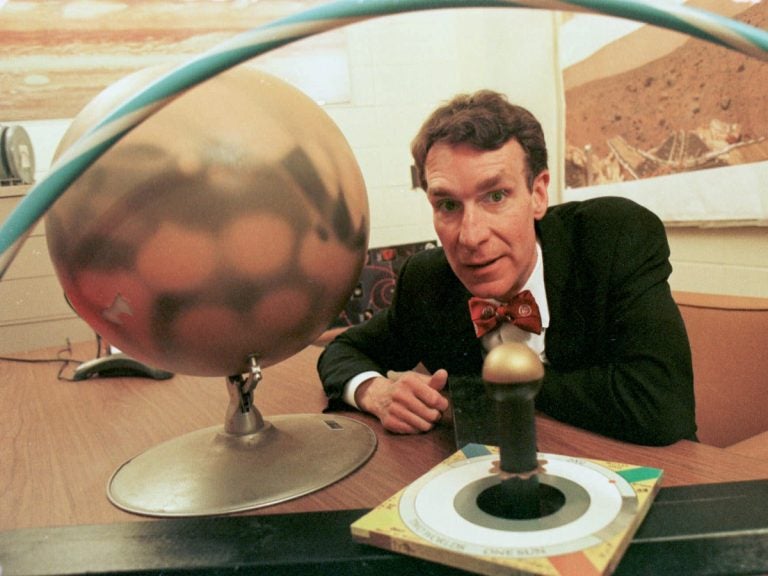

Bill Nye in his television show, "Bill Nye, The Science Guy." (AP Photo/Michael OKoniewski)

Often we think about “Star Wars” movies as science fiction, but they really aren’t.

Bill Nye the Science Guy says yes, it’s confusing.

When I spoke with him, Nye said, “Now when you say ‘Star Wars,’ I think you mean ‘Star Trek,’ and by that I mean ‘Star Trek’ has an optimistic view of the future with science. ‘Star Wars’ is a religious story or Shakespearean tale.”

In “Star Wars,” you’re not supposed to question how a spaceship can go faster than the speed of light or how the Force works. It might as well be magic.

The line between science and magic is often blurry, and on early science television there was sometimes a battle between the two. TV creators weren’t sure about how to balance information and entertainment.

Back in the 1950s, the United States government wanted to do some positive marketing for nuclear energy, so they asked Walt Disney to give it his magical touch.

He made a TV special called “Our Friend the Atom.”

Ingrid Ockert, a science historian finishing her dissertation at Princeton University, explains, “Walt Disney walks on stage and he tells the viewer that he’s going to tell them a story about how a young fisherman accidentally released a genie out of a bottle.”

The genie looks like a mushroom cloud, kind of like the clouds you see after a nuclear explosion.

Next, scientist Heinz Haber explains that this genie could kill us all, but it could also help us: “As we developed our story of the atom, we made an amazing discovery. We had a science story, but suddenly we realized that it was almost like a fairy tale.”

Ockert says “Our Friend the Atom” then takes viewers on a magical journey of scientific progress. It looks like a Disney production, with animation as good as what you can see in “Sleeping Beauty” or “Peter Pan.”

That fairy tale about science certainly captured people’s imagination; teachers showed the program in classrooms for decades

Around the same time, there was a very different kind of science show, one more like a cooking show.

Don Herbert, an actor from Chicago, was the star and creator of “Watch Mr. Wizard.” He guides children through fun experiments, like how to hold a banknote over a flame without burning it, or how to glue two pieces of wood together so that they can hold more than 80 pounds of pressure.

Tom Nikosey, president of Mr. Wizard Studios and Don Herbert’s son-in-law, says there was still magic, but it was completely different from what Disney did.

“Magic traditionally is a sleight of hand to where the audience is amazed at the result of a magic trick,” he says. “Mr. Wizard’s magic was that he brought you behind the scene and showed you how the trick worked.”

But if you ask historian Marcel LaFollette, the early science TV programs of the ’50s and ’60s like “Mr. Wizard,” “Our Friend the Atom,” and others didn’t really work.

“What it failed to do was to do any effective education on how we judge what is and is not science, how we judge and how we assess the reliability of science, should we trust science and why,” LaFollette says.

LaFollette wrote two books about science on the radio and TV, and she says scientists back then could have used the new medium of television to give people a free science education that was exciting and entertaining. But, instead, a lot of them turned up their noses.

“We see lots of evidence, especially in the ’50s and ’60s, where the scientific community really pulls back from engagement … dismisses television as unimportant or too flashy and glittery, and therefore does not engage with television producers themselves or with the networks,” she says.

“They say, ‘Television, oh, that’s where the comedians are, that’s where the entertainers are, that’s not for serious discussion like science.’”

Not all scientists shied away from public engagement.

Astronomer Carl Sagan became famous for his 1980 TV show “Cosmos.”

He was a household name and even went on shows like Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show.”

Other scientists didn’t like that.

But Carl Sagan operated on the idea that, if scientists didn’t offer compelling answers to people, then people would find them elsewhere, like in pseudoscience.

Historian Ingrid Ockert says in his writing Sagan makes the case that “Pseudoscience is absolutely appealing; it fills this emotional need that people have.”

The appeal may be that pseudoscience is magic, dressed up as science, without having to obey any of the rules and procedures that science has to follow.

“And scientists, science communicators especially, need to recognize that, because if they don’t recognize that, then people are going to continue watching these bad shows, they’re going to continue to say that they believe in UFOs, and you know what? It’s our fault for not creating an appealing narrative.”

In the 1990s, “Bill Nye the Science Guy” hit the scene, and it drew directly from what came before.

Bill Nye says, “The pitch for the Science Guy show was Mr. Wizard meets Pee Wee Herman.”

Nye had rules for his show, as explained in his 2015 book: The science has to be real. No fictional machines that do magic tricks.

He’s a big believer in educating people about science to help them make better choices. And that’s why he layers it in theatrics, to make sure his audience pays attention and understands.

Nye’s strategy worked, says Derrick Pitts, the chief astronomer at the Franklin Institute, a science education museum in Philadelphia. He says the success of science TV personalities like Bill Nye and Mr. Wizard gave science teachers around the country permission to make science fun.

“One of the things I’ve found that works extraordinarily well in teaching science is something that we commonly see today in almost every science demonstration of every kind, and that is blow it up or set it on fire,” Pitts says.

Pitts is an astronomer. He can’t make planets blow up, but he can show people something cool and shiny.

“I can begin any discussion about any topic in astronomy, I don’t care how esoteric it is, if I begin with one of three or four things, one of them being, ‘Hey let’s take a look at the moon through a telescope. Isn’t that exciting?’ No one’s going to turn that down. I also find that no one’s going to turn down an opportunity to talk about either aliens, or black holes,” he says.

And the best part about all of these things? They’re real.

“When you start to look at the universe in its complexity in almost every facet, sure a lot of it looks like magic, but guess what? It’s far more fascinating to find out that it’s not magic.”

And that, he says, is just as much fun as watching “Star Wars” movies — which he loves, by the way.

You can explain black holes; just don’t try to explain how the Force works.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.