How researchers and advocates of color are forging their own paths in psychedelic-assisted therapy

After a long history of erasure, communities of color are reclaiming psychedelic traditions to heal from trauma.

Listen 11:54

A person bags psilocybin mushrooms at a pop-up cannabis market in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

We’re seeing an explosion of medical research into psychedelics. Psilocybin, or shrooms, to treat major depressive disorder. Ayahuasca, a psychotropic plant medicine from the Amazon, and ibogaine, a potent hallucinogen from Africa, to treat addiction. LSD for anxiety.

MDMA, also known as ecstasy or molly, is currently in Phase III clinical trials — the last phase before Food and Drug Administration approval. If results hold up, it could be used in therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder by early 2022.

But some researchers are pushing for MDMA and other psychedelics research to be more inclusive. A study from 2018 found that 82% of participants in psychedelic studies were white.

That means there’s a greater likelihood these treatments will be developed in ways that don’t work for people of color.

Furthermore, practitioners may be overlooking a huge opportunity with psychedelic-assisted therapy — using it to treat racial and intergenerational trauma within communities of color.

‘I felt like I was alive again’

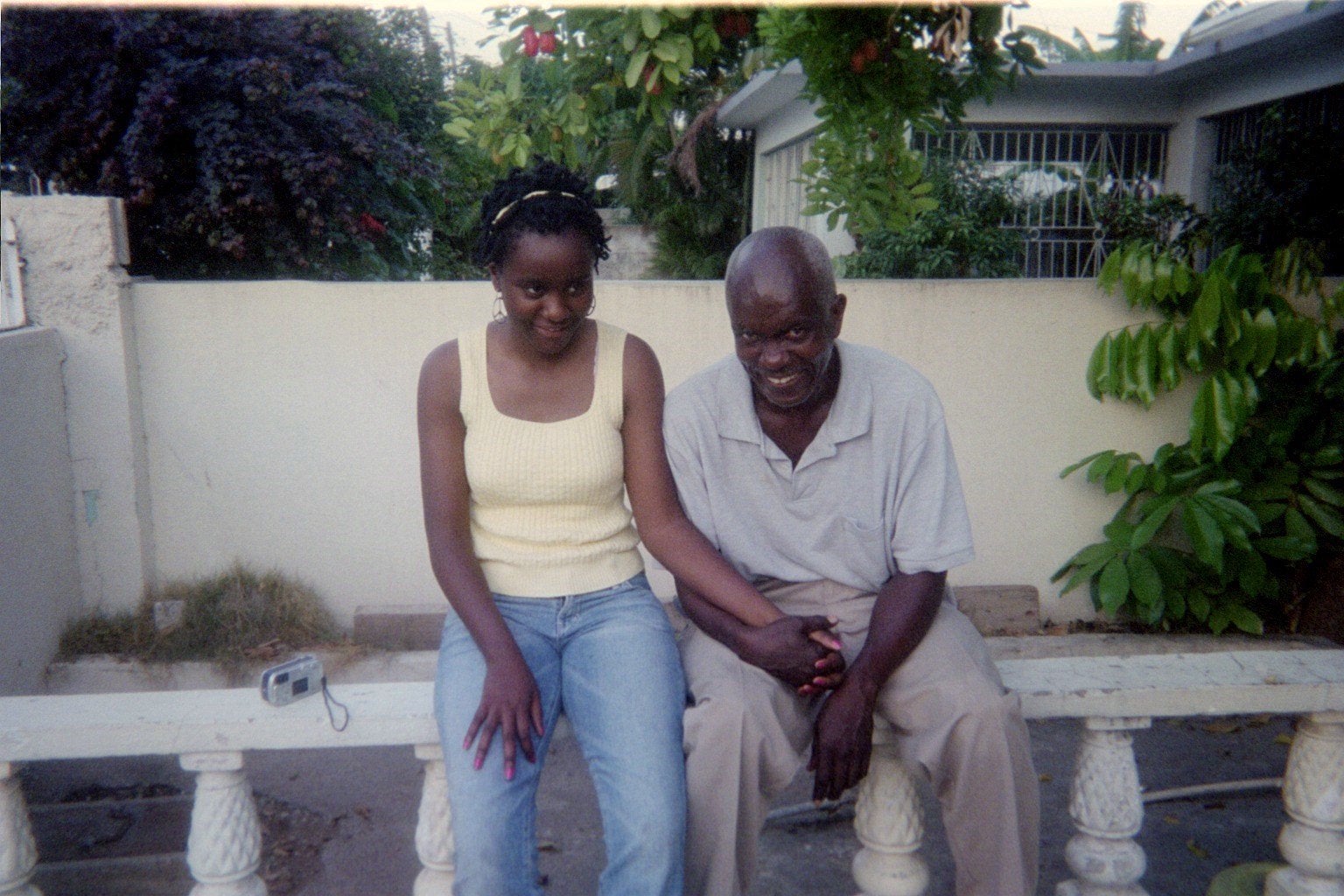

When Ifetayo Harvey was 4 years old, her dad was sentenced to 15 years in prison. She says an undercover cop had propositioned him to sell cocaine, and as a new immigrant, working to support his family, he accepted. He served eight years, before being deported back to Jamaica.

“This shaped my childhood experience in a way that’s hard to explain,” Harvey said. “Because things like this aren’t supposed to happen, right?”

Through her childhood, Harvey often felt sad or angry toward herself. She had trouble trusting people.

“I was really confused about what happened with my dad, and who he was as a person,” Harvey said. “As a kid, I dealt with depression and anxiety and suicidal thoughts.”

In college, Harvey learned about psychedelics as a therapeutic substance. She was a senior, feeling depressed and struggling to graduate.

She decided to give it a try. She took some shrooms, then went on a walk with a friend through the woods of western Massachusetts. It was fall in New England, the woods wearing their most stunning colors. At first, she says, the sensations were overwhelming.

But once that passed, she felt an authentic sense of happiness, for the first time in a year.

“I felt like I was alive again,” Harvey said. “Before, I just felt really dull and lifeless and numb, and not really motivated to live.”

During her walk, she saw life all around her.

“I saw plants breathing, I saw things move and sparkle in ways that I hadn’t seen before. I also felt just spiritually connected to the earth in a way that I haven’t had,” she said. “I got a reset, and I needed that to be able to graduate.”

Shrooms have helped Harvey heal and process a lot of the trauma she and her family went through.

“I’ve been able to look at myself with more compassion, look at my family with more compassion,” she said. “When you’re in a sober state of mind, it’s harder to process heavy things sometimes because we want to run away from it or we want to bury our feelings. And with mushrooms, you can’t really do that. Mushrooms kind of makes you face whatever you’re running away from.”

An exclusionary culture

That year, Harvey started learning more about psychedelics and psychedelic research. After she graduated in 2014, she was excited to get a job with one of the biggest psychedelic research organizations around — the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS.

When she got there, she was the only Black employee, and she felt like she didn’t belong. Her feelings came to a head during a classic psychedelic experience, in Chicago.

“My first time taking LSD was at a Grateful Dead show with MAPS,” Harvey said. “I’m there, I know one Grateful Dead song, but I was offered LSD by one of my colleagues and I partook in it. And I was having a great time.”

When she and her colleagues walked out of the concert, they saw Deadheads everywhere, she says, being wild up and down Michigan Avenue. As they approached Grant Park, they noticed police putting a Black man in handcuffs.

“Mind you, there’s all these white folks running around probably on drugs, selling drugs, have drugs on them, doing God knows what,” Harvey said. “The one Black guy you see at the concert is, of course, getting arrested.”

She recalled that someone asked, “Should we stop and watch to make sure they don’t mistreat him?” To which her other coworkers responded, “He probably did something or you don’t know what he did, let’s just keep it moving.”

“That, to me, was kinda just representative of how Black folks are seen,” Harvey said.

This was one of many times Harvey felt alienated by her white coworkers. Though they knew about her family’s history with drugs and incarceration, people didn’t check if she felt safe when everyone used substances. They didn’t seem aware that her risk, and connection to drugs, was different from theirs.

“It actually kind of, it feels like you’re in a twilight zone,” she said. “It’s very frustrating because I believe that psychedelics can be powerful and can be healing and can do amazing things for our world. But I think that we have to be very intentional and thoughtful about how we do that.”

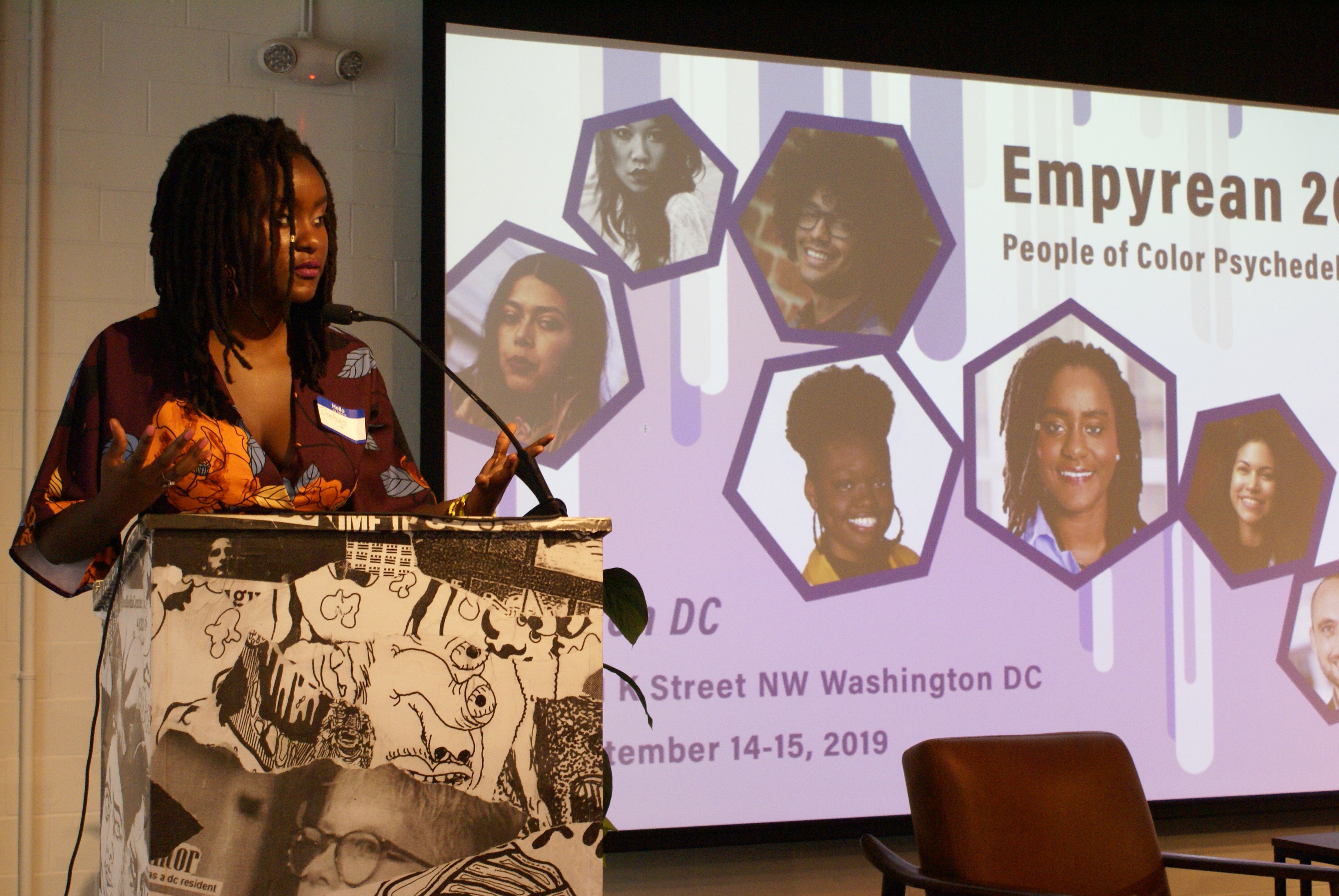

Eventually, Harvey got a new job with a nonprofit called the Drug Policy Alliance. And she also co-founded a group called the People of Color Psychedelic Collective.

“I really wanted to create a space that is truly open and also safe for folks of color,” she said.

The whitewashing of psychedelics

Right now, psychedelics are gaining traction in mainstream medicine. But the big names behind psychedelics, the leaders of research organizations, and the therapists doing psychedelic-assisted therapy are all mostly white.

There are reasons why the mainstream psychedelic movement is not very diverse. Elijah Watson is a journalist who’s written about what he calls the whitewashing of psychedelics.

Psychedelics originated in communities of color, he said. Indigenous groups have used them as medicine and sacrament for thousands of years. In some cases, those traditions are alive. In other cases, they were banned or destroyed through colonization.

Then in the 1950s, a white bank executive from the United States went to Mexico and participated in a Mazatec mushroom ritual.

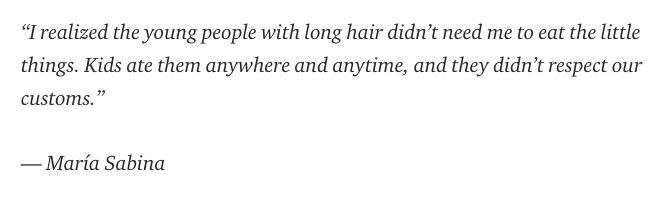

“His name was Robert Gordon Wasson,” Watson said. “He went to Mexico, and he found a medicine woman named María Sabina. And he took the mushrooms himself.”

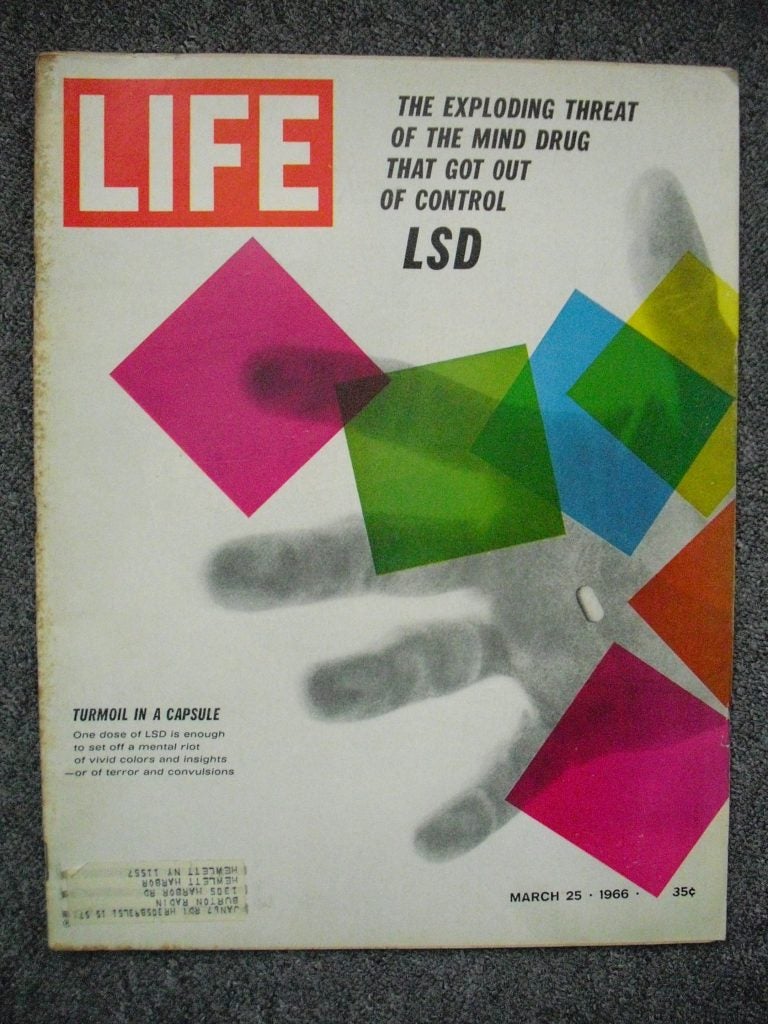

Sabina let Wasson take her picture on the condition that he keep it private. But when he got back to the U.S., he published the picture, and the name of her community, in a “Life” magazine article called “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.”

That article is credited with sparking an interest in psychedelics that caught fire across the U.S., especially within the hippie movement. Countercultural figures like author Ken Kesey and Harvard professor Timothy Leary took on the mantle of psychedelics.

And “you have it emerging within countercultural music during the ’60s, where you’re having sub-genres like psychedelic rock,” Watson said.

After the article came out, Sabina’s community was bombarded by hippies who wanted to hallucinate on shrooms. Local police blamed her, and people ended up ostracizing her and burning her house down.

During this time, researchers and psychiatrists were also digging into the use of psychedelics.

Not all of this research was aboveboard or, for that matter, ethical. MK-Ultra, Project BLUEBIRD and Project ARTICHOKE are the names of top-secret CIA programs, in which the government used LSD, mescaline and other psychedelics to manipulate people’s mental states.

The CIA also backed open research, such as the work of Harris Isbell in Lexington, Kentucky, in the 1950s and ’60s. Isbell did experiments on incarcerated Black men, often with a history of drug addiction. He wanted to test how much LSD someone would tolerate, and for how long. He’d give people LSD doses for 77 days in a row.

Though it was coercive and abusive, the work was published in respectable journals. Isbell had people sign simple consent forms and paid them off with drugs. Experiments like this led to public distrust in psychedelic research, especially in Black communities.

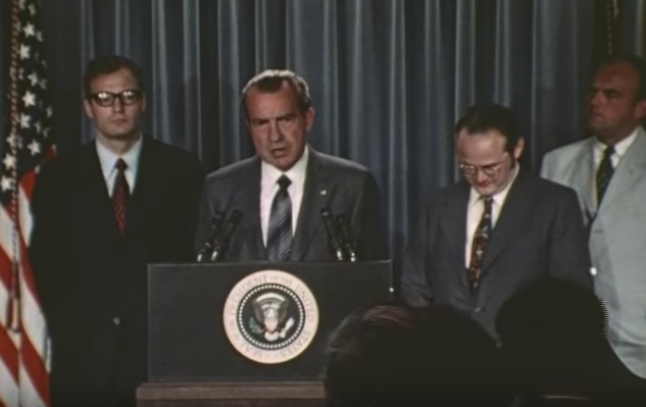

By the 1970s, the antiwar and Black Power movements were gaining strength. Richard Nixon declared a war on drugs. Research into psychedelics shuttered, practically overnight. And drugs became a reason to search people’s homes and cars, and put them in prison.

“Black and Brown people are more disproportionately being arrested and targeted during this still very ongoing ‘war,’” Watson said.

While white people have continued to use psychedelics, he added, Black people have many reasons to stay away from them.

“My livelihood is already in jeopardy even by just smoking some weed,” Watson said. “We also see how police officers tend to treat people of color with mental illness. It’s, ‘We’re going to shoot first and ask questions later.’ If I’m going to partake [in] this substance that may make someone think I have this mental illness, and I see how cops already treat them, what’s to say that they’re gonna treat me any differently?”

New efforts toward inclusion

Because there’s so much mistrust, MAPS, the organization that studies psychedelics, has had trouble convincing people of color to join their clinical trials.

“Once the Phase II [MDMA] trials were completed, we saw that we didn’t have the diversity that ideally we would have wanted,” said Brad Burge, the director of communications for MAPS.

“If you look at the history of the stigma and prohibition of these substances, it seems like a miracle that we were able to get the approval that we needed,” he said. “And so we were just hoping that we could enroll enough people in those Phase II trials and get approval.”

With Phase III, which will have 200 to 300 participants, MAPS wants to include more people of color. So a few years ago, the organization reached out to a psychologist named Monnica Williams.

Williams is a Black woman herself, and she’s spent her career addressing mental health disparities. She’s worked with many people who are traumatized from experiences of racism, stigma and discrimination.

“We know that people in communities of color may have a lot of additional trauma beyond the usual suspects,” Williams said. “So beyond assault and combat, things like cultural traumas due to genocide, slavery, immigration trauma and refugee trauma.”

When someone has experienced trauma, it shatters their trust in the world and their feelings of safety. It causes them to be perpetually on the lookout for danger.

“If you look at experiences of racism and discrimination, you really see the same thing happening, because people are continually assaulted,” Williams said. “Could be large things, major discriminatory experiences, or it could be a lot of small things, but they’re coming unpredictably. And eventually you start to fear for your own safety. And then when you try to talk about it, oftentimes it’s dismissed. So you’re still just holding onto it and carrying it around.”

People of color also often hold intergenerational trauma. Black folks who’ve been in the U.S. for generations “have a whole family legacy of slavery and Jim Crow laws and hate,” Williams said. Researchers have found that trauma can get passed down biologically, she said, through changes in how genes are expressed.

There is a lack of therapists of color, or even white therapists who are trained to think about these things, Williams said.

“Often, it’s just not on clinicians’ radar,” she said. “They’re not thinking about the fact that maybe being strip-searched by a law enforcement person felt like a sexual assault. Being threatened at work, maybe that landed on someone like a death threat.”

The power of MDMA

Williams has trained in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy with MAPS, and she believes it has a lot of potential to treat PTSD.

“The treatments we have now for PTSD are not that great,” she said. “The medications are ineffective. They just sort of numb people’s emotions. And the therapies can be effective, but they’re very difficult. Often, patients just don’t feel able to deep dive into their past traumas.”

Right now, the therapies that are most effective, like prolonged exposure, require people to recount their traumas in harrowing detail. With MDMA and other psychedelics, Monnica sees something completely different.

“People are able to move through their traumas with a lot less pain and fear,” she said. “People are making new connections in their brains, and changing how they’re thinking about their trauma. I don’t know, I think it’s a beautiful process really. In a way that I wouldn’t say is necessarily true of traditional therapy.”

Scientists don’t fully understand how MDMA works in the brain. They know it reduces activity in brain regions that process fear, and stimulates the release of feel-good neurotransmitters, like oxytocin, which enhances feelings of trust and bonding.

“But then there’s also things that we don’t necessarily understand,” Williams said. “A lot of people have very spiritual experiences. Sometimes, people may feel like they’re talking to deities, they may see ancestors, they may feel like they’re getting wisdom from spiritual guides.”

It’s also common for people to feel a sort of ego-death, which puts things in perspective. Or to find compassion.

“They’re able to forgive themselves a lot of times. What keeps people stuck in PTSD is they blame themselves for the traumas that have happened to them,” Williams said. “So you do see big shifts in the way people think. And a lot of it does seem to be, you know, connected to love. And that just sort of helps to melt away the trauma.”

Williams said she has to practice therapy a bit differently when she’s treating patients with psychedelics. With prolonged exposure therapy, she’s always directing people to the hardest parts of their story.

“I don’t do that with MDMA therapy,” she said. “People in a lot of ways are healing themselves. It’s a nondirective type of therapy. For example, if they say, ‘I see a door,’ we might encourage them to go through it. It’s mostly what we call inner-directed. They’re sort of listening to their hearts and going in that direction.”

Lingering questions of access

For all its potential, there are still concerns that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy will be hard to get once it’s approved. It’s a 12-week course, and requires two therapists for ethical reasons, so it will be expensive. And there still aren’t enough therapists of color.

MAPS said it is working on convincing insurance companies that this approach is cheaper than traditional PTSD therapies, which can take a longer amount of time to work. And in August, Monnica helped MAPS put on a Cultural Trauma & Psychedelic Medicine workshop specifically for therapists who work with communities of color.

Aisha Mohammed, a Philadelphia-based therapist who attended that training, has spent much of her career working with sex workers, drug users, and people who don’t have housing.

“It’s been difficult for some of the clients I see to make regular appointments, or to even come into sessions. And the trauma has been so disruptive to their lives that conventional therapy isn’t a good fit for them,” Mohammed said. “So this idea that you could address longstanding, deep traumas in a three- to five-month window is really life-changing and transformative.”

Mohammed is part of a team that’s opening an MDMA-assisted psychotherapy clinic in Philadelphia, called the SoundMind Center. The nonprofit clinic will offer sliding-scale treatment, and will have a community organizer on staff whose job is to raise awareness and build trust with communities that have been affected by the war on drugs.

She hopes to also see Philadelphia’s community health agencies, which offer free or low-cost therapy to people with Medicaid, hire practitioners trained in psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Mellody Hayes is another practitioner of color who attended the MAPS training in Kentucky. She’s a San Francisco-based anesthesiologist who focuses on palliative care, and plans to open an inclusive psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy center called Ceremony Health.

“Psychedelics are the first medicine we have that is a way to experience liberation,” Hayes said. “The medicine is in how we live in community and connection with one another.”

With psychedelics, “you can experience more peace,” she said. “And what are you going to build with that peace? They say that we create from what we know — if what you know is pain and trauma, you will pass forward pain and trauma. And if what you know is peace and joy, you will create peace and joy.”

For Elijah Watson, the journalist who’s covered the history of psychedelics, what’s important about this moment is that people of color are speaking up — and people are listening.

“If you don’t have somebody who does look like you advocating for the thing that could possibly help you, yeah, you’re probably not going to do it,” Watson said.

The erasure of history has led Black and Brown people to think psychedelic healing “was never a part of us,” he said. “But it always has been, and we deserve access to it, just like anybody else. The main goal of therapy is to get better. And that’s something we should all be able to strive for.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.