Rediscovering fun: Why grown-ups need to play

Playing doesn't end with childhood. It's important for adults too, just in a different way.

Listen 12:31

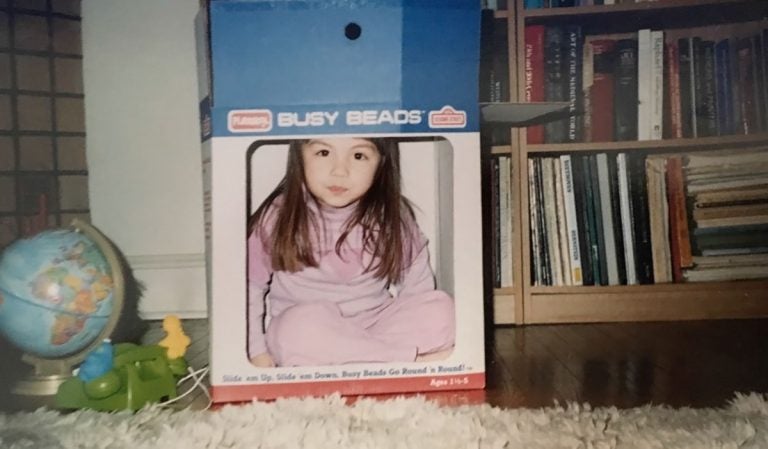

Liz Tung, at 3 years old, pretends to be on television using a cardboard box. (Image courtesy of Liz Tung)

I discovered I had a problem with playing when I started asking friends and colleagues what they did for fun.

Video games, soccer, game nights with friends — it seemed like everyone had a thing … everyone except me.

Not that I hadn’t tried. When I first started reading about the importance of adult play, I’d dutifully bought myself a coloring book and a set of pastels, carved out time to entice my cat with string, even rediscovered the computer games I’d loved as a kid. All of it bored me, and I’d invariably return to my same, sedentary forms of leisure.

“I think a lot of the time for fun, you either browse Reddit, watch `X-Files’ or go window shopping on Amazon and other sites,” my husband told me. “Or look for sofas.”

Did any of that count as play? Did I need to overhaul the way I spend my free time — and rediscover how to play?

The history of play research

To find out, I contacted Stuart Brown, widely regarded as the guru of play research. He’s in his 80s now, and has been studying play for roughly 50 years.

Brown’s journey into the science of play began in 1966, when a 25-year-old former Marine named Charles Whitman climbed to the top of a tower at the University of Texas and gunned down more than 40 people.

Texas Gov. John Connally convened a commission of doctors and scientists to investigate what had led to Whitman’s murderous rampage. Among the investigators was a young Stuart Brown — an internist, psychiatrist, and clinical researcher who was recruited for his work with violent offenders.

After in-depth interviews with Whitman’s friends and family, the commission came to a surprising conclusion.

“What was determined by the commission,” Brown said, “was that a highly disturbed, omnipresent father had suppressed from the beginning of his life all efforts on Whitman’s part to play. And this was agreed upon by the commission itself, even though there were many other circumstances that would have led to potential violence on his part.”

Brown was so struck by this conclusion that he launched a multi-decade career dedicated to the study of play.

Though researchers continue to struggle with how to define play, Brown has zeroed in a few key elements.

“It’s a kind of a state of being in which you’re engaged in an activity for its own sake,” he said. “It produces a sense of joyfulness or fulfillment, and it takes you out of a sense of self or time so that your engagement is deep.”

So deep, in fact, that Brown has come to view play as almost a biological imperative.

“It is deeply embedded in nature,” he said. “It’s a different state from all others. It’s as different biologically, from my standpoint, from normal consciousness as sleep and dreams are also from normal consciousness.”

Benefits of play

And just like sleep, play affords plenty of important benefits.

“There are a number of things that are valuable for both children and, I think, adults in terms of play,” said longtime play researcher Garry Chick.

In children, play serves a crucial role in cognitive, physical, emotional, and social development.

“There are emotional and social skill areas of the brain that develop during play, and do not develop very well if animals are deprived of play,” Chick said. “And in fact, animals deprived of play, and children deprived of play, seem to not function as well socially.”

Play serves a different, but still important, role for adults.

“Well, I think the first thing you get is a sense of lightening of mood,” Brown said. “If we’re at play, we get more optimistic about life. We are open to making new connections and seeking out novelty.”

By contrast, absence of play can have serious negative consequences.

“When there is serious adult play deprivation, what you see is a kind of a smoldering depression,” Brown said. “There are things such as optimism and engagement in something that’s fulfilling, in a sense of one’s life being authentic, that are also not as vital when play is missing.”

Chick has theorized another potential reason for adult play — selecting a mate.

“We have in fact bred ourselves to be playful,” he said. “In general, we prefer mates who are playful to those who are not.”

Chick says playfulness in a potential mate signals different advantages to men and women.

“What we find across many species, including humans is that adult males are frankly dangerous,” he said. “And so females may wish to select a playful male because that male is giving off signals that he’s not dangerous either to her or her offspring.”

For men, Chick says, a playfulness in a female mate may “in effect be signaling that she has youthful characteristics and is therefore very high in fecundity.”

All of which means that while play may not serve an immediate concrete purpose, scientists speculate there may be a greater evolutionary purpose to why different species play.

Defining play

The question, then, is what counts as play?

According to Garry Chick, researchers have struggled for years to agree on a standard definition.

“That, of course, has been a major problem,” Chick said. “Over the years, there have been numerous definitions of play, and nobody’s really been very satisfied with much of any of them. I’m always reminded of the Supreme Court justice who was unable to define pornography, but claimed that he knew it when he saw it. And I think play is pretty much the same. It’s difficult to define, but we know it when we see it.”

However, a few years back a biologist named Gordon Burghardt offered up a definition that Chick says provides some useful criteria.

The following is a simplified summary of the five criteria.

First, it has no immediate survival value. Second, it’s spontaneous, voluntary, intentional, pleasurable, rewarding, reinforcing, and/or done for its own sake. Third, it differs from strictly functional expressions of that behavior in at least one respect. Fourth, it’s repeated. And fifth, it’s performed when the animal is relaxed — or, as Chick says, “fat and happy.”

Researchers have broken play down into various subcategories. For Chick, there are three big ones.

“One is object play — playing with things,” he said. “Another might be called locomotor play. So that would be simply things like running and jumping and, you know, sort of acting exuberantly. And the other big category is social play.”

All of which leaves the field wide open when it comes to figuring out what counts as play. Intention and circumstance, it seems, can be as important as behavior.

Play histories

Stuart Brown developed his own technique for helping adults rediscover how to play — what he calls play histories, which involve extended interviews that reach back to his patients’ earliest years. He gave a few examples of the questions he asks.

“For example, show me the pictures of yourself when you were an infant. What do you see? What’s your natural tendency? Do you like visual things? Auditory things? Tactile? What produces glee. Can you remember what you were told your initial temperament and personality were like? Did you have pets? Did your parents allow you to go on vacation or have birthdays? What were your toys?”

To find those answers for myself, I paid a visit to my parents and dusted off my baby album.

“You were very placid,” my mom commented as she flipped through pictures of me as an infant.

“In fact, you would fall asleep while you were feeding, and I would have to kind of flick the bottom of your feet with my fingers to get you more alert.”

That changed when I started walking and interacting with the world, my parents said. I became more energetic and got excited about playing — specifically, about playing pretend.

“There was a lot of pretend, and there was a lot of imagination,” my mom said. “What you didn’t do was play much with toys. You weren’t indifferent, but you weren’t fascinated either.”

Toys served as a conduit for my sister’s and my imaginative play. We had a stuffed animal family with an entire backstory, and little houses that we’d built in our closets. As we got older, that creative energy evolved into something like improv.

“It was like you were always writing, extemporizing skits with each other, with these sort of imaginary characters,” my mom said.

My parents ticked off other behaviors they remembered: my fondness for doing impersonations; my habit of performing at the dinner table; dressing up our cat in costume jewelry.

When I reflected on what that imaginative play might look like in adult life, it occurred to me that that kind of storytelling wasn’t so far off from my job as a reporter. The difference is, instead of inventing characters, I’m interviewing them. And instead of performing at the dinner table, I record their stories.

Of course, the context for this storytelling almost automatically precludes it from being defined as play. Multiple scientific definitions of play emphasize that play behaviors are to be done for their own sake — which jobs most emphatically are not.

Still, if you remove the financial incentive, Chick said there’s no reason why work-like behaviors can’t count as play, so long as you find them rewarding.

In fact, Chick — who’s retired — said “work” is what he does these days for fun.

“Mostly what I do — and this may sound awful — but I get a kick out of doing research,” he said. “That’s my play. And seriously, people are really going to think, `What kind of a lunatic is this guy?’ — doing statistics and computer programming, I find to be playful.”

As for my original forms of fun — sitting on my tuckus watching Netflix, reading Reddit, and shopping for couches — Chick said that, according to definitions like the one proposed by Gordon Burghardt, they aren’t exactly play, but are play-adjacent.

“I think that most leisure/play researchers would regard all three scenarios that you listed as leisure, but not play,” he said. “However, each could also be done in a playful manner (probably more easily in a social rather than individual situation). So, what does that make them? And this, of course, is the reason why neither play nor leisure has any universally accepted definitions.”

For me, it’s close enough … I’m happy with my couch potato fun. Besides, figuring out how to play again ended up being a lot more work than I had imagined.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.