Pa. dairy farmers struggling to find greener pastures in tough milk market

Along stretches of farmland on South Lincoln Avenue in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, you will notice yard signs with bright orange letters that read, “SAVE OUR LOCAL DAIRY FARMS.”

Listen 4:56

Alisha Risser owns and runs a dairy farm in Lebanon county. Having been in the business for 17 years, Risser said low milk prices in recent years have been really hard for farmers. (Min Xian/Keystone Crossroads)

Along stretches of farmland on South Lincoln Avenue in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, you will notice yard signs with bright orange letters that read, “Save Our Local Dairy Farms.”

Alisha Risser owns one of those farms.

Seventeen years ago, Risser and her husband started a contract with Swiss Premium, a brand of the national distributor Dean Foods. In those days, Risser said business was good.

But lately, the dairy industry across the country has been struggling with declining consumption of liquid milk and many farmers are having a tough time turning a profit.

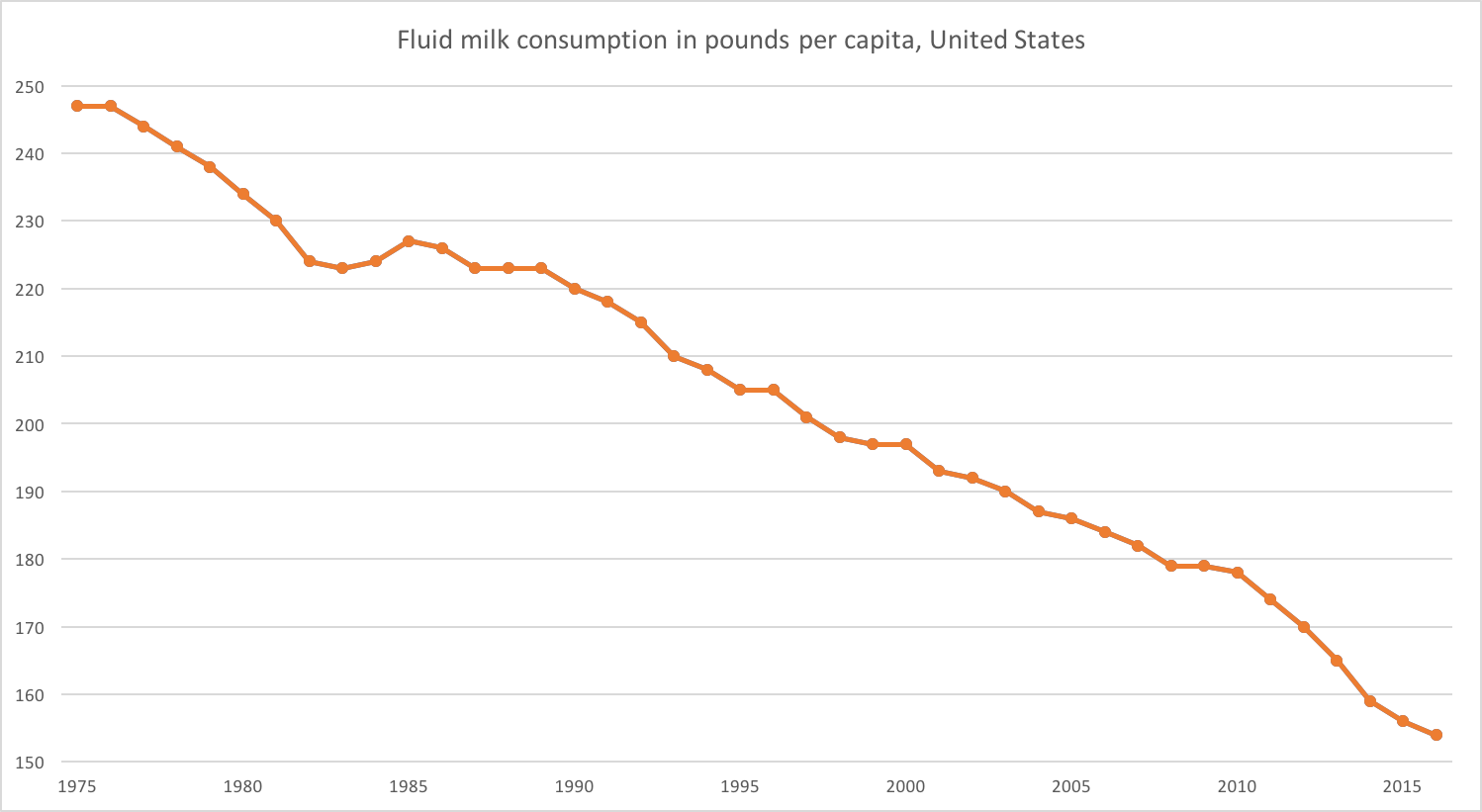

Three decades ago, Americans drank 247 pounds of milk on average in one year, but by 2016, consumption dropped to 154 pounds per capita, according to the USDA. The decline is attributed to a series of factors including the prevalence of more milk substitutes, medical debates over milk’s health value, and ethical debates about production.

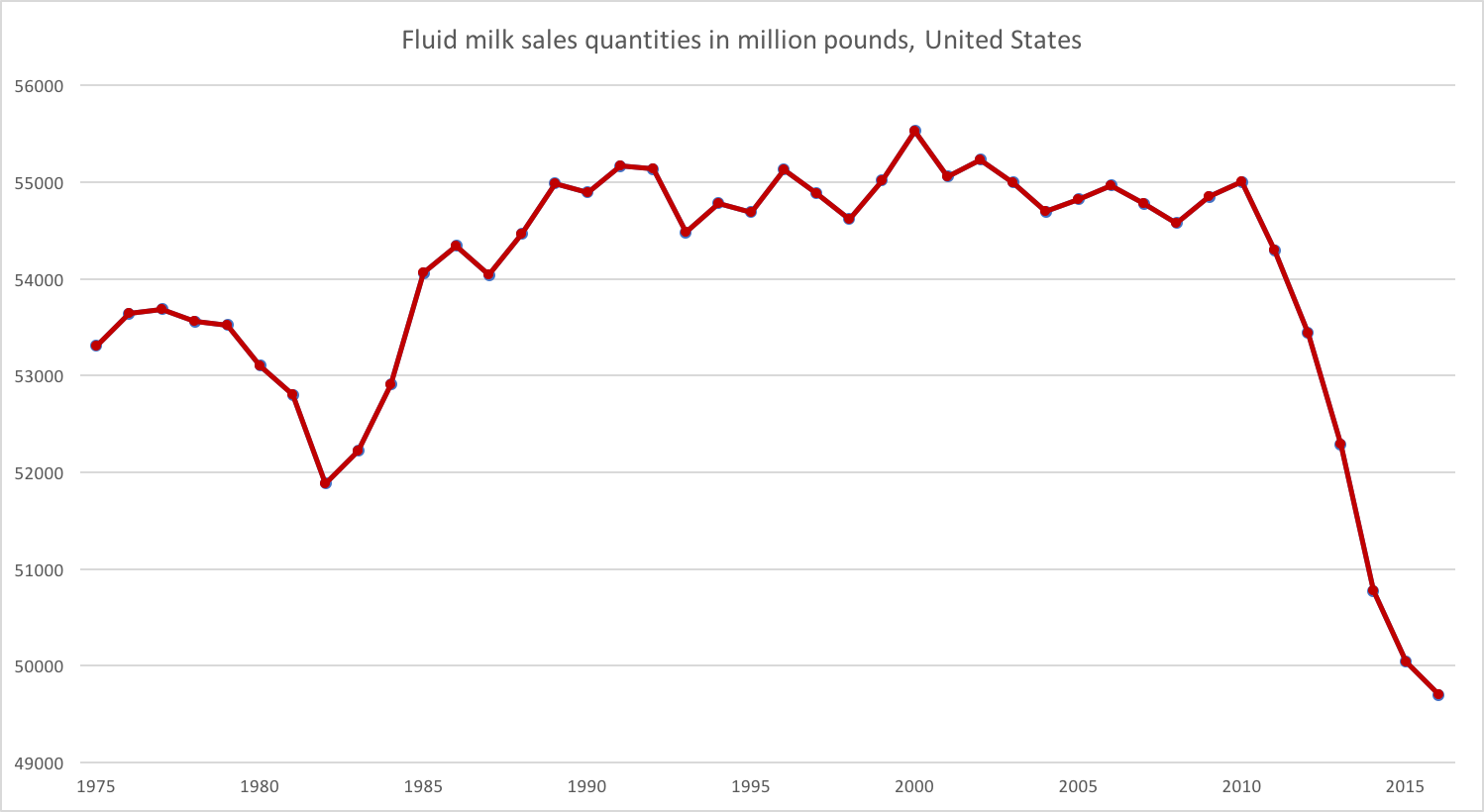

With fewer people drinking milk, competition among producers has grown increasingly harsh.

When Dean Foods announced in March that it was ending contracts with more than 100 dairy farms nationwide, that included the Rissers farm in Lebanon and 41 others in Pennsylvania.

They received termination notices saying their contract with Dean would end by June. The company says the decrease in sales left them no option.

Risser said the decision came as a surprise and left farmers very little time to react.

“If you lose your milk market, there is just not options out there,” Risser said.

The Rissers considered selling their farm and their 80 cows. But, by the beginning of April, Harrisburg Dairies offered a life-line, announcing that it would pick up nine of the farms, including the Rissers.

“We’re nervous about the direction the dairy industry is going to go,” Risser said. “But this immediate crisis — to have that burden lifted off of our shoulders is tremendous.”

The Rissers consider themselves lucky. According to the Center for Dairy Excellence, Pennsylvania lost 120 dairy farms in the past year. Between 2010 and 2018, 830 Pennsylvania dairy farms went out of business.

Having worked on farms from a young age, Risser said she understands the volatility of the industry.

“The ability for a farm to make a profit is always going to be a challenge,” she said. “It would come and go in highs and lows, where the lows wouldn’t last for long. What we’re seeing currently is just a long stretch of low prices.”

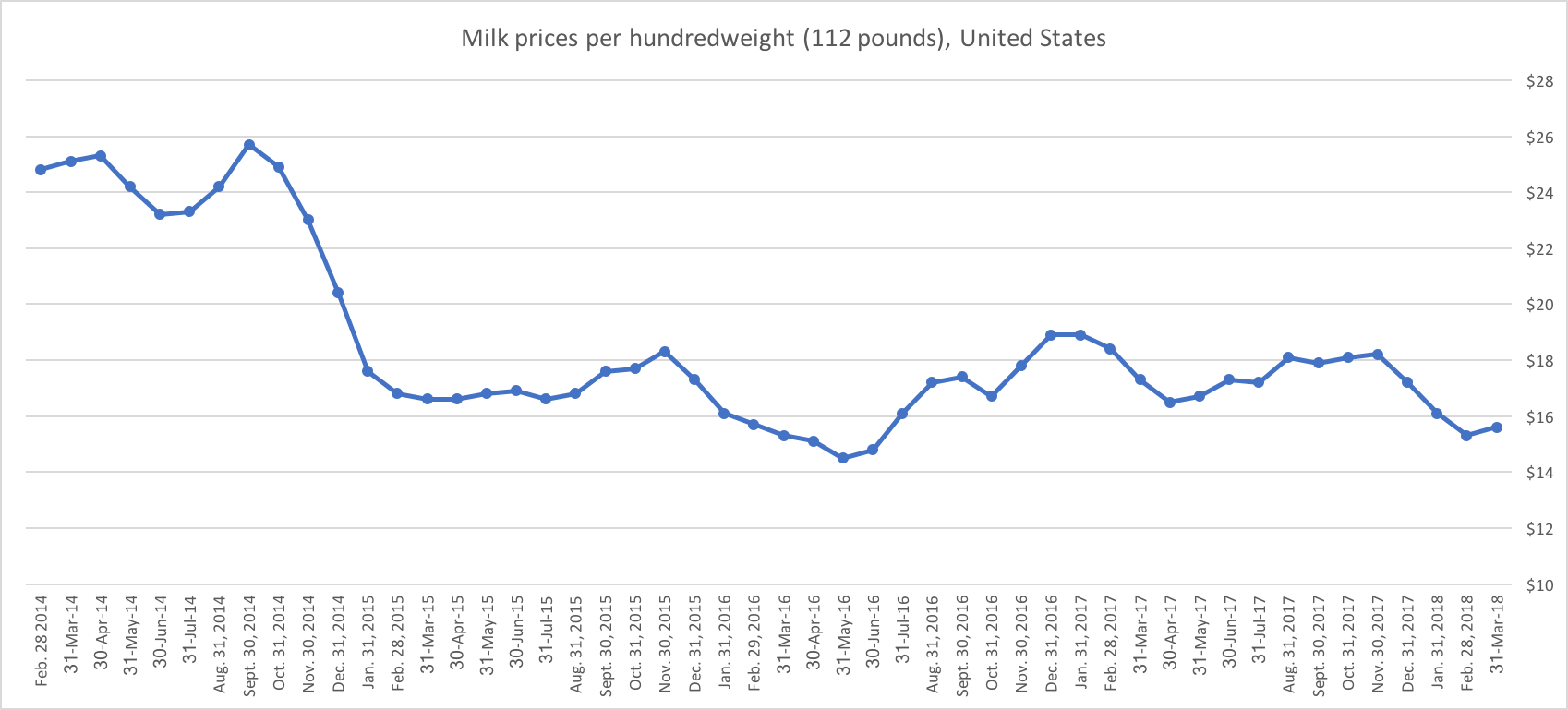

Across the country, the price farmers get for milk has been dropping. It’s now about three quarters of what it was in 2011.

At the same time, Risser said it’s costing farmers more and more to make milk. The USDA says dairy farmers are getting paid 87 cents for every dollar they spend to produce.

“I think most farms are not making enough money per month to pay their bills, so for every month that we’re on business, we’re losing money,” Risser said.

As prices have decreased, farmers have increased production to try to make up losses. But as more supply has flooded the market, the selling price for farmers gets driven lower. Jim Goodman, a Wisconsin farmer and president of the National Family Farm Coalition calls it “a vicious cycle.”

In the U.S., state and federal government have a role in determining milk prices. Goodman says government could do more to help family farmers.

“In the United States, it seems there’s never been any questions of how much production is too much,” Goodman said.

To find a remedy for this crisis, Goodman’s group wrote an open letter to members of congress and the USDA asking for an immediate raise in milk prices nationwide. They proposed a $20 floor price for each hundredweight, or 112 pounds, for milk.

“We need some kind of an emergency relief right now because farmers are losing their farms,” Goodman said. “They can’t pay their bills. This impacts the whole structure of the rural community.”

But, Dave Swartz, assistant director of Penn State Extension, a research center that advises farmers, is among those who are skeptical of the idea.

“From the human side that sounds very compassionate and important, and we do care very much about the people who operate these farms,” Swartz said. “Unfortunately, when the government intercedes in a part of the economy like that, it often has maybe unforeseen effects.”

Swartz said raising the minimum price will simply allow milk from other countries to become more competitive. “It’s possible that some of our industries that use milk would import milk just because they could buy it cheaper than what they could buy it from our own farmers,” Swartz added.

He said even if some farms go out of business, it’s a natural result of market place economies.

But it’s a very tender subject. A study from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that farmers have the highest rate of suicide in the United States.

In Lebanon county, the Rissers are grateful that they have a new deal.

About four dozen of dairy farms in the area are still working with Dean Foods, but Alisha Risser said at least two who are losing their contracts are planning to sell their cows.

“There are a lot of farms, good farmers that are having to sell out right now, and our thoughts are with them,” Risser said. “It’s tough.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.