Overhauling its bus network may be on SEPTA’s schedule soon

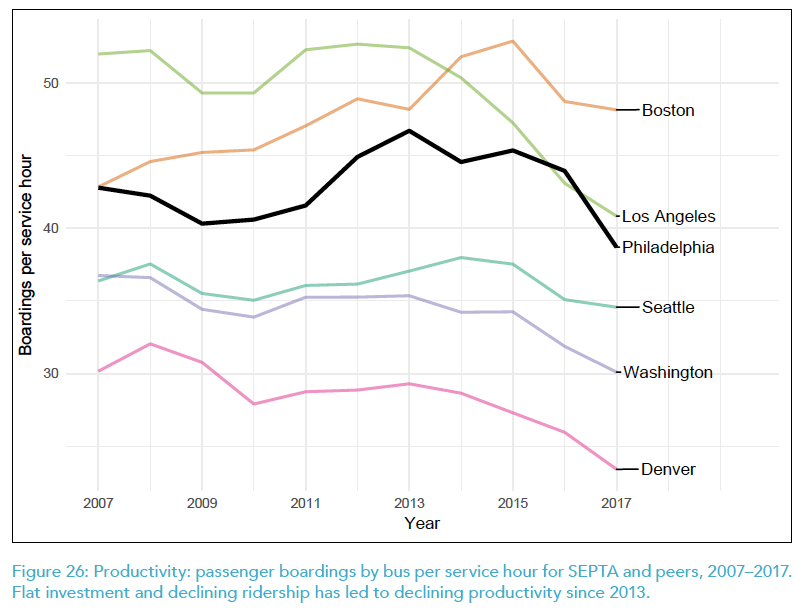

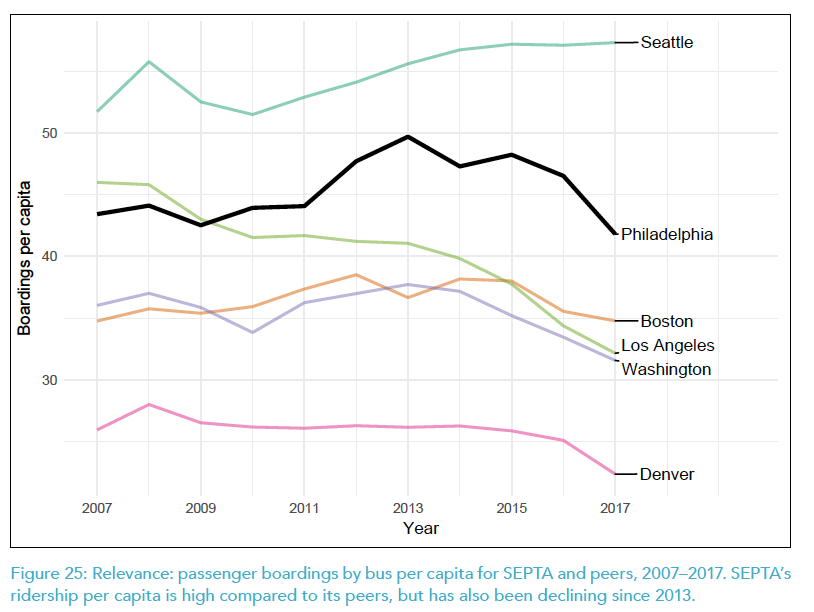

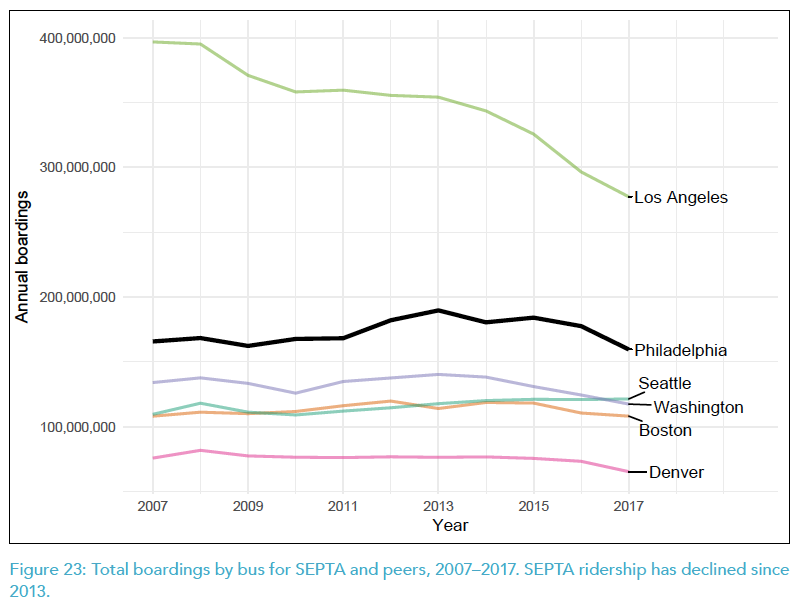

Though overall ridership has remained relatively flat, bus trips have fallen 33 million, or 17 percent, over the last five years.

Listen 1:45

SEPTA's Route 15 trolley. (PlanPhilly)

Buses are the sick man of SEPTA’s transit options. Though overall ridership has remained relatively flat, bus trips have fallen 33 million, or 17 percent, over the last five years. Now, after a yearlong examination, transit consultant Jarrett Walker has turned in his official diagnosis: A complete bus-network redesign that may include amputating SEPTA’s transfer fees and Girard Avenue’s Route 15 trolley.

With the report in hand, SEPTA appears ready to act to staunch the bus-ridership bleed. The transit agency will begin soliciting bids for a “team of consultants” next month, said long-range planning manager Jennifer Barr, and that group will spend the next two to three years working on a comprehensive overhaul of how SEPTA operates its buses.

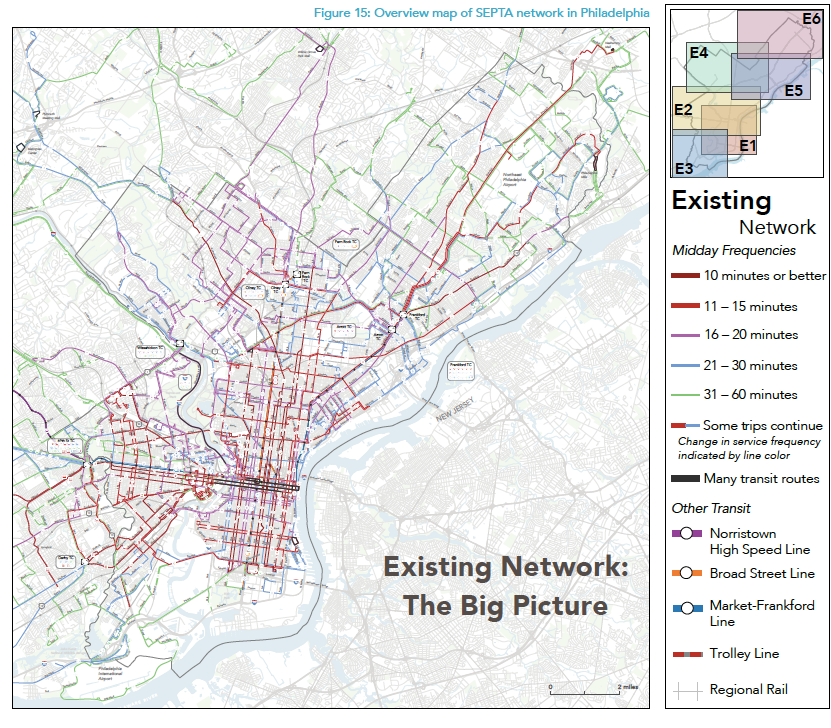

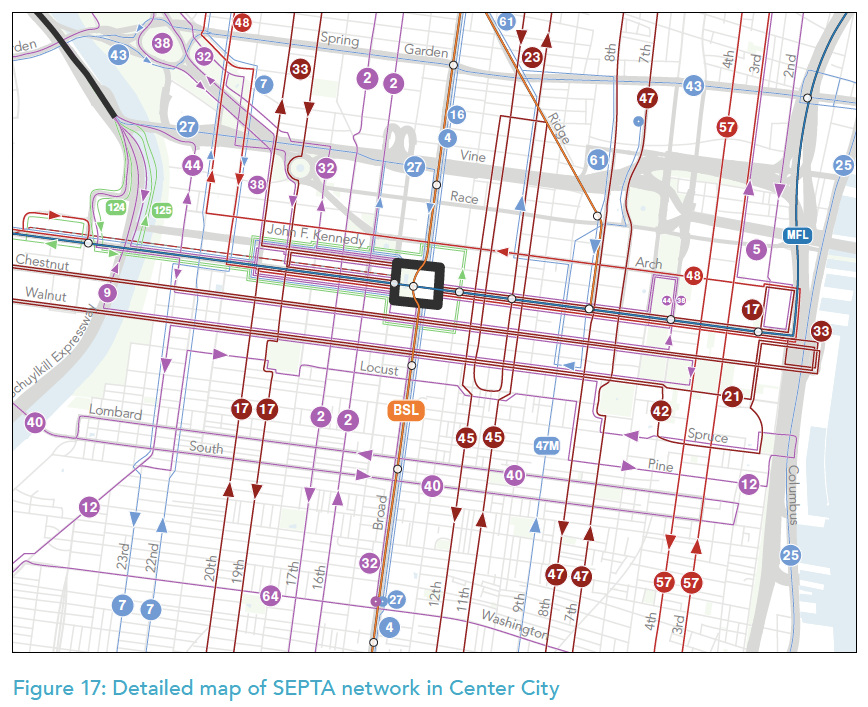

Joined by SEPTA senior staff and a representative from Philadelphia’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems at the transit agency’s headquarters, Walker presented his findings on the state of the city’s bus network, which largely comports with what PlanPhilly reported in May. While Jarrett Walker + Associates focused on the state of city transit, SEPTA plans to reimagine the entirety of its bus network, including the suburban routes.

Walker’s report will serve as a guideline for that all-encompassing effort.

“Fundamentally, it’s the process of pretending there is no network and drawing from scratch,” said Walker. “Inevitably, you end up putting back something that looks 70 to 90 percent like the existing network, but the goal is not that. The goal is to draw a new network from today’s needs only. So that you know – when you’re done – that your network is not about history. It’s about the present.”

Walker adopts a philosophical approach to the question of increasing bus ridership, giving equal weight to ontology and on-time performance.

“We’re all imprisoned to relative degrees, where the walls of our prison are where we can get to in a reasonable amount of time, and beyond that range of where we can get to in a reasonable amount of time are jobs we can’t hold, schools we can’t go to, clubs we can’t belong to, people we can’t meet in person,” said Walker. “And so, when we expand that, when we expand where people can get to in a particular amount of time, that’s not only access to jobs and opportunity, but in a more fundamental sense it’s expanding people’s freedom. Because your freedom to do anything that involves leaving the house depends on your transportation options, depends on whether you can get there.”

The best way to increase bus ridership is by “expanding freedom as much as possible for as many people as possible,” he said. “If you want to do that for a lot of people, what you do is draw a pattern of high-frequency lines forming a connected network, reasonably fast and reliable, and with a focus on places where you service a lot of people, which is to say plays that are dense, walkable, linear, proximate.”

Over 100 pages, the report scrutinizes SEPTA’s current bus network and offers a series of policy “choices” – not recommendations – for the agency and its stakeholders to consider, presenting each as a cost-benefit analysis between alternative visions for how Southeastern Pennsylvania’s buses should operate.

The most fundamental example of the choices Walker presents SEPTA sets the mutually exclusive goals of maximizing ridership and maximizing coverage area against each other. To serve more areas with transit means the buses travel farther and come less frequently to pick up fewer riders. To boost ridership means the buses focus on fast and frequent trips between densely populated areas.

The “choices report” presents a rough framework for how SEPTA would go about redesigning its bus network, starting by asking civic leaders, business owners, elected officials, and regular riders how SEPTA should balance the trade-offs in the new network. How far are people willing to walk if it means they’ll wait less for the next bus? How many times are people willing to transfer if that means a faster overall trip?

With a sense of how radical a change Philadelphians will be willing to support, SEPTA and its consulting team would be able to go about plotting the actual route changes and operational tweaks.

“A full network redesign study would clarify those trade-offs, engage the public and civic leaders in an intense conversation about the tradeoffs,” said Walker. “In other words, we would want a public and stakeholder process that would tell us what rules we should follow in actually redesigning the network.”

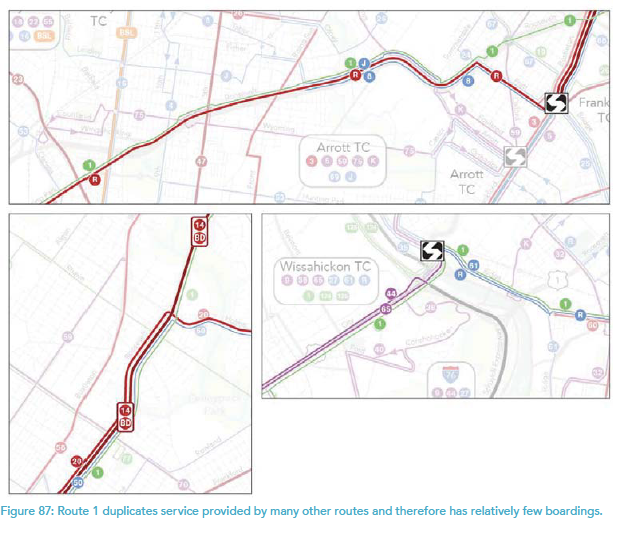

Walker broke down the conceptual balance of SEPTA’s current bus network’s allocation of resources between ridership, coverage area, and waste. He said roughly 70 percent of SEPTA’s buses promote high ridership, 15 percent go towards broad coverage, and the remaining 15 percent is basically wasted — 10 percent on duplicated routes and 5 percent on running excessive service during rush hours.

By “duplication,” Walker means routes that overlap needlessly, and he provides Route 1 as an example. That bus goes from Parx Casino in Bensalem to the edge of St. Joseph’s University by way of Roosevelt Boulevard. It’s the only bus that makes that specific run, but there are plenty of other routes that run along Roosevelt Boulevard between Bensalem and the Frankford Transportation Center, and then another set of buses that run between there and along the lower half of Roosevelt Boulevard, and those routes run more frequently than the once-an-hour Route 1. If SEPTA scrapped Route 1 and reallocated the buses and drivers on it to those other lines, the other routes could run even more often.

Walker also identified another 5 percent of SEPTA’s service as “excess peak.” Per his calculations, SEPTA’s buses are actually more crowded midday, between the morning and evening rush hours, than during those actual peaks. That isn’t to say rush-hour buses aren’t crowded – they are. Or that most of SEPTA’s passengers ride midday – they don’t. It’s that each midday bus, on average, is slightly more packed than the average rush-hour bus because ridership drops only a bit midday as SEPTA runs a lot fewer buses.

Those figures are more conceptual guidelines than precise measurements. They also refer to the amount of service, measured in vehicle hours – one bus running one hour – not the number of routes. So even if SEPTA set out to reallocate 15 percent of its buses, it would not necessarily mean that 15 percent of its routes would disappear or change.

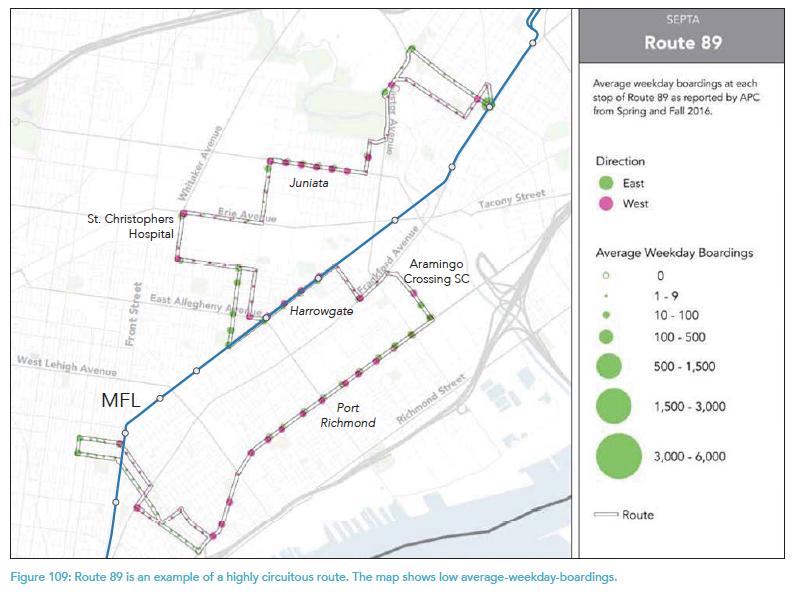

Circuitous routes are the most likely to see major changes – the report singles out Route 89, which zigzags around the River Wards, as a bus line that would be better off replaced by increasing service on nearby routes (such as the 5, 25, 56, 60 and 75) and encouraging riders to transfer.

Walker’s report also calls on SEPTA to consider abandoning the Route 15 trolley, which mostly runs along Girard Avenue, and replacing it with a high-frequency bus line, citing the streetcars’ inability to get around double-parked cars and other obstacles that frequently obstruct its path.

Increased congestion has slowed down traffic all across Philadelphia in recent years, and SEPTA’s buses have been no exception. Walker pointed to the prevalence of double-parked cars and other jam-causing traffic violations as a major contributing factor, calling for the city to step up enforcement. Parking violations are largely the purview of the Philadelphia Parking Authority, and executive director Scott Petri said he’s eager to crack down on parking scofflaws.

“Everybody else might be going on vacation for the summer, but we’ll be very, very busy,” said Petri. “All of those transportation partners are going to use the summer as an opportunity to see if we can tackle this issue.”

“In a city like Philadelphia, a robust, well-run, well-funded transit system definitely reduces traffic,” he said, adding that if SEPTA ridership continued to decline “we would have a traffic nightmare.”

“In the end, the impact [of traffic] to the city and the business district in an economic sense is significant,” said Petri.

In recent years, the business community’s grousing over traffic has grown steadily as the delays getting through Center City have also grown. News of the impending overhaul was met with applause.

“The bus network redesign is long overdue, and has been shown in other places to be a cost-effective (not very capital-intensive) way to optimize/improve transit coverage [and] service. Particularly important now with the impact that [ride-hailing companies] are having on bus ridership,” wrote Jeff Hornstein, executive director of the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia.

The plan is for the network redesign to be essentially cost-neutral: After the expense of the redesign itself, new signs, new maps, and trying to inform riders about the changes, the actual operations would not cost more. When asked for a rough idea of the cost, SEPTA Deputy General Manager Rich Burnfield declined to say what the agency was estimating. Still, all told, the redesign will likely cost tens of millions of dollars over a few years – far less than the amount SEPTA expects to spend replacing roofs on some of its depots and garages.

Philadelphia is just the latest city to hop on the bus-network redesign trend. Houston launched newly designed bus network in 2015, Baltimore in 2017. New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, and Boston all are either redesigning now or planning to redesign soon.

Public-transportation ridership doesn’t reflect just the quality of the transit service – it competes for passengers with private cars, taxis, ride-hailing, and other options. People weigh cost, convenience and comfort and pick an option that’s best for them, and if other transportation forms become cheaper or faster, folks will give up on the bus. The period of SEPTA’s declining bus ridership overlaps with gas prices going down and staying down. At the same time, the economy picked up (meaning more people could buy new cars, or fill up their tanks), and ride-hailing became prevalent.

Besides reallocating buses from less-ridden and repetitive routes, Walker advocated for increasing SEPTA’s focus on bus loops and transportation centers. “There is a ring of transportation centers around the edge of the city – 69th, Wissahickon, Olney, and Frankford – all of which are real power points in the network.” he said. “Every route that goes into them, its value is multiplied by all the other routes there. Because if you go in on this route, you can get to all these other places.”

The report also calls for making SEPTA’s bus network easier to use by developing new maps that would show all service options – SEPTA’s current system maps show only rail, leaving out buses – and highlighting frequent service on those maps.

“We strongly recommend and support SEPTA’s initiative to look at all-door boarding,” said Walker. “All-door boarding is an extremely efficient way to speed up service, because so much delay occurs at the stop with the process of boarding and fare payment.”

All-door boarding would allow bus passengers to get on at the back door, whose use is usually limited to letting passengers off. Though SEPTA hasn’t signed off on the concept yet, let alone the specifics of how it would work, most buses with all-door boarding rely on a combination of a fare-card reader at the back door and the honor system – albeit one backed up by periodic enforcement through random ticket checks.

“This is the one speed-improvement process that SEPTA can really lead on its own,” Walker added. “Most of the other speed-improving opportunities require cooperation with the city.”

The report calls for better coordination between SEPTA and city government, specifically the creation of a transit planning office so that the city actively generates its own public-transportation goals, rather than passively responding to SEPTA’s requests. Policy director Chris Puchalsky said the city’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems is currently working on a transit plan.

While OTIS seems eager to support SEPTA’s redesign effort, garnering the support of Philadelphia’s politicians, particularly City Council, may ultimately determine how radical, and how successful, a network redesign might be.

EditDeleteMap of SEPTA’s existing bus network in Center City, West and North Philly (Jarrett Walker + Associates)

Other, far less ambitious adjustments to the city’s transportation network have been met with opposition by change-averse neighborhood groups who often have the council’s ear. The design and implementation of SEPTA’s new Route 49 – set to begin operations in the fall – took more than three years. It took city officials even longer to attempt a nine-month pilot of protected bike lanes on Market Street and JFK Boulevard — the idea was first floated back in 2009.

Michael Noda, a co-founder of the urbanist advocacy group 5th Square, said he and his fellow transit advocates were “feeling pretty vindicated” after hearing some of Walker’s proposed changes. “This is basically putting on the table everything that we’ve asked for in the last several years,” he said, noting that 5th Square testified about ending the $1 transfer policy during SEPTA’s fare hearings last year.

“We are also strongly in favor of JW+A’s recommendation for transit-only lanes through congested areas,” Noda added in a follow-up email. “Most of all, we agree that making the bus network a more useful choice for more Philadelphians will require strong political leadership from SEPTA and elected officials, and we look forward to putting City Council candidates on the record about their transit priorities during next year’s primary elections.”

SEPTA and OTIS believe that this larger project will succeed quickly, whether smaller projects have been delayed or killed outright by local opposition, precisely because it is so epic in scale.

“It’s actually easier, in the long run, to do the big study that looks at how it could all be different, because then you can show how much larger the benefits are,” said Walker. “Then it becomes clear that if you’re opposed to this thing over here in the study, then you’re also opposed to the larger benefits of the study, and it’s going to be a different conversation.”

“We want Council to think about, in general, ‘How do I feel about a better network for my constituents – about my constituents being able to get to more jobs and more opportunities?’ ” Walker added. “And how does that weigh against someone being angry because we’re changing the bus route? That’s the actual trade-off.”

There’s no use trying to figure out how to win over City Council yet, he said. Not before the actual redesign process begins, when they’ll be asked to contribute to the upfront discussions that will inform the size and scope of the changes SEPTA considers.

“What I find over and over again,” Walker said, “is if we show big enough benefit to what we’re doing, things that were politically impossible become possible.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.