Lack of doctors puts rural mothers and babies at risk

Listen

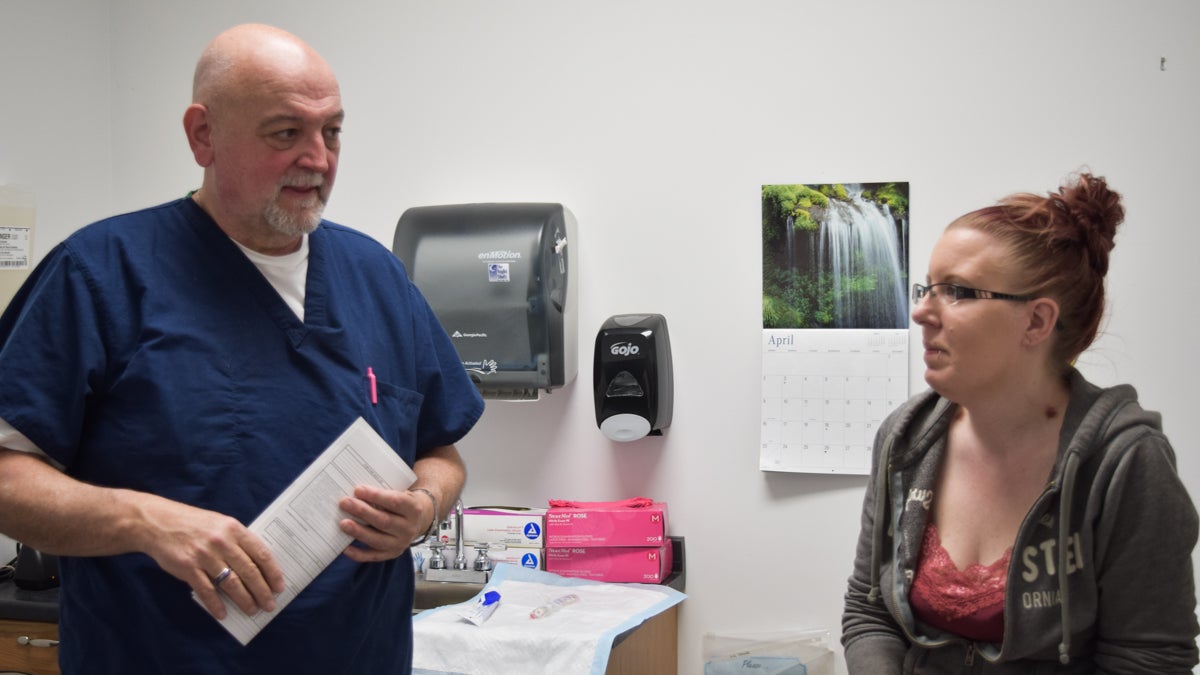

Dr. John Zimmerly reassures one of his pregnant patients, Kim. (Elizabeth Fiedler/WHYY)

Shawnee Baker was in labor — and her husband was trying his best to get her to the hospital in time. As they bumped along country roads, she imagined frightening scenarios, and giving birth to her daughter along the side of the road.

“I was scared — like, ‘Are we going to get there in time?'” Baker said. “Like, especially for my first one, because you don’t know what to expect. And if not, what happens then?”

Baker lives in rural Pennsylvania, near the New York border. In rural America, the country’s shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists is perhaps most keenly felt. Experts predict it will only get worse, expecting a shortage of 8,000 OB-GYNs nationwide by 2020. For pregnant women and their babies the stakes are high: America has the highest maternal mortality rate among industrialized countries.

Baker made it to the hospital to deliver her daughter. When she had her son, she brought him home on an hourlong journey through a January snowstorm.

This is life for many pregnant moms in rural America: hoping that they’ll make it to the hospital before the baby arrives. And they don’t just do this once. They make the trip for regular doctor’s visits during the nine months of pregnancy as well, packing a bag of snacks, some water, and driving more than an hour just to get their vitals checked and hear the baby’s heartbeat.

Baker said the OB-GYN shortage makes pregnancy hard for a lot of women in the northern reaches of Pennsylvania, especially because many people don’t have cars. And even if they do, they often don’t have gas money. She sums up the situation in four words: “This is not okay.”

The traveling ‘jack of all trades’ doctor

But if you’re a pregnant woman out here in rural Susquehanna, Pennsylvania, population 1,500, this is your reality. There’s one local option for OB-GYN care, but he comes to town only three times a month.

John Zimmerly can’t quite decide on a single title for himself. He’s a jack of all trades, he said: “MD, laborist, private practitioner, rural practitioner, a little bit of everything.”

Zimmerly just made the two-hour trip here — to the local health clinic — in the shadow of a rusty old water tower, along an old railroad line. He’s came from one of his other jobs as a laborist at a hospital in upstate New York. He’s already tired from delivering babies throughout the early morning.

“So, therefore, I look tired,” he said.

Zimmerly is in his 60’s, with a bald head and a diamond stud earring that catches the overhead light inside the office. He could be winding down toward retirement. Instead, he insists this rigorous workload is necessary to serve his patients. As a kid, he spent his summers out here said he’s doing his best now to give back to the community he loves so much. To ensure women get the regular prenatal care that’s recommended, he comes here a few times each month to make access to that care a little easier for them.

Dr. John Zimmerly travels two hours to treat pregnant patients at a health clinic in rural Susquehanna, Pa. (Elizabeth Fiedler/WHYY)

His first patient of the day, 32 year old Kim, is here with her boyfriend. They drove 20 minutes to get to the doctor and she is visibly nervous. She’s 14 weeks pregnant.

“This is my first child. I don’t know what to expect.” Kim tells Zimmerly the baby’s not moving so she’s been worried something’s wrong. He explains to her that it’s too early to feel baby movements. He tells her not to worry.

“You know this still moves me,” Zimmerly said. “You could easily take things for granted. The whole process fascinates me. That you can take two cells that you can’t even see and put them together and form a person that can hear and smell and think etc. It’s amazing to me. More and more so.”

It’s amazing to Kim’s boyfriend Dominic too. He’s sitting in the corner with a smile. He said he cried when he heard the baby’s heartbeat just a few minutes earlier.

“It was actually amazing to hear a little heartbeat. I’ve thought somethin’ was wrong for the past couple weeks.”

Dr. Zimmerly assures the couples that the exam went well. He asks if they have questions and then gives Kim some basic health advice. “It’s better to have five or six small meals throughout the day rather than, you know, two or three big ones. There’s a tendency toward a fasting hypoglycemia which means if you’re not eating for even 3 or 4 hours during pregnancy can drop.”

Delivery not included

Zimmerly used to make weekend trips to rural Pennsylvania to deliver babies at a hospital just up the road. He’d have patients induced on Friday, so he’d be by their side when they delivered during the weekend. But that’s not an option any more: like hospitals across the country the one up the road no longer delivers babies. Some blame it on the high cost of malpractice insurance, other hospitals simply didn’t want to deal with the worst case scenarios like maternal hemorrhaging.

Inside his office in Lock Haven, right in the middle of Pennsylvania, surrounded by state forest land, family physician Thane Turner provides cradle to grave care. His patients span the spectrum from newborns to geriatrics.

“Sick visits and sutures and broken bones, and simple things like that,” said Turner. “So, yeah, primary care in rural America kinda sees a wide range of things.”

Turner grew up here and after his medical training, he came home. He’s been back as a doctor for 20 years and for the first decade he delivered babies on top of his regular practice.

“The difficulty was that labors can be long and involved,” he said. “And it was hard. Because there would be days that something would happen and you’d have to run out of the office and that was, you know, eight to 10 patients that had to be inconvenienced with you leaving.” It wasn’t just the patients’ lives that were disrupted. Turner stopped delivering babies 10 years ago because he was also tired of missing his kids’ baseball games and church activities when the call came for a delivery. Many family physicians like Turner are doing the same thing: not delivering babies.

Looking for solutions

In other parts of rural America the OB-GYN shortage is even worse. To ease the crisis, states across the country are considering a variety of solutions. One of the newest is at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, the nation’s first rural residency OB-GYN program.

Director Ellen Hartenbach said the first resident starts this summer with rotations at hospitals outside the city.

“I think of it as a best of both worlds. They’re going to get all the clinical skills they need but they’re also going to get training in in a smaller community hospital so that they can understand what it’s like to practice there,” Hartenbach said.

She said doctors who get trained out in the country just might fall in love and decide to stay. “People tend to practice relatively close to where they did their training. There’s a certain amount of familiarity,” she said.

Hartenbach said this is an important mission, because in pregnancy things can quickly go from ok to terrible. She said women in rural areas get prenatal care less often. “And that can lead to problems. We also know that there are some national data that the infant mortality rate and maternal mortality rate are higher in rural areas.” She said it’s not totally clear whether that’s due to poverty or whether it’s access to care.

Could other players in the medical system be part of the solution?

Eugene Declercq, a professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, said in most industrialized countries around the world, midwives attend a majority of the births. “And virtually all of the lower-risk births.” Declercq said in the United States that midwives attend less than 10 percent of all births.

But even midwives, like obstetricians, tend to live along the coasts and in large cities. That leaves huge swaths of underserved families across the middle of America. Declercq said training more midwives to work in underserved rural areas would help.

In the meantime, pregnant women in rural areas continue to make long treks to hospitals — hoping they arrive in time. And pregnant women in Susquehanna are hoping their one doctor, John Zimmerli, doesn’t retire too soon

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.