How diabetes has shaped my life — two perspectives

Catherine Price has Type 1 diabetes; Keysha Brooker has Type 2. As part of The Pulse’s “The Cost of Diabetes” episode, we invited them to our studio to meet.

Listen 7:00

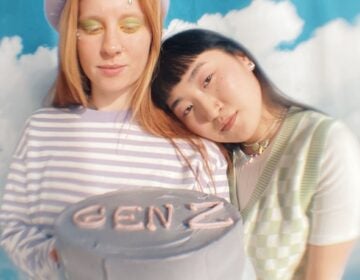

Catherine Price has Type I diabetes, Keysha Brooker has Type II. Over the course of an hour, they shared with one another how diabetes has defined them and impacted their lives. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Catherine Price has Type 1 diabetes; Keysha Brooker has Type 2. As part of The Pulse’s “The Cost of Diabetes” episode, we invited them to our studio to meet.

They spoke for over an hour. We had trouble getting them to wrap up.

Listen to excerpts from their conversation below.

When Catherine Price was a senior in college, she dragged herself to student health services after experiencing a string of “weird” and unrelenting symptoms that included intense fatigue and insatiable thirst. The diagnosis? Type 1 diabetes.

That meant Price’s body had stopped making insulin. From there she entered “a new normal,” having to upend her diet, check her blood sugar levels regularly and take artificial insulin. Without the medicine, she could die.

“Which is kind of crazy for me to think about because [insulin] was only discovered in 1922,” Price said.

Keysha Brooker learned she was at risk of diabetes when she was 25. Type 2 diabetes runs in her family, but she remembers the doctor telling her to “just lose the weight, just stop eating cake and cookies.”

The implication that the disease was her fault “really stuck with me.”

In general, Type 2 diabetes means a person’s body may still make insulin, but not as well as it should. That can get worse over time. Carbohydrates can further wear out cells’ ability to make insulin, so strict diet and exercise may slow the disease’s progression.

Brooker takes medication in pill form and avoids everything from oranges to fried food, all of which can be high in sugar. When her blood sugar levels are high, she can feel helpless.

“You’re hoping it goes down,” she said. “So I used to be afraid to check it. And it’s hard to check it, and it’s hard not to check. Because if you check it and it’s high, you want to starve yourself for the rest of the day. If you check it and it’s normal, you’re like, ‘Yay! Now I can eat something.’”

Brooker is 45 years old now and says she went from prediabetes to diabetes following her pregnancy. She is hyper aware of the stigma that can surround Type 2. As a community health worker, she has seen others “get chastised” for having the disease.

“It’s a very complicated diagnosis to deal with and [people] just feel like you’re lazy,” she said. “With me working in the hospital and meeting some patients that have gotten to the point where they get amputations or are blind — doctors, I see them even toward those people, like, ‘How did you let yourself get to this?’ Or, ‘Now you have to get your foot amputated because you didn’t watch your diet and you didn’t take your medications.’”

Price is now 39 and as a science writer, she has written about having Type 1. She says people with Type 1 seem to “get off easier” than those with Type 2. It’s an autoimmune disease, she says, so “no one accuses us of getting it on ourselves.”

For both Brooker and Price, saying “no” is a constant theme in their day-to-day. No to ice cream on a hot day. No to that breakfast spread at the morning meeting.

“Thanksgiving is horrible! I don’t even celebrate it any more,” Brooker responded. “I was like the best baked macaroni and cheese maker in the family — closest to mom’s — and sweet potato pie. But you have to taste those things. I can’t do this.”

For Brooker and Price, this delicate relationship to food as a result of their diabetes, affects other parts of their lives. Brooker says she doesn’t go out a lot because food is so deeply ingrained with socializing, and that can create uncomfortable situations.

Price can relate.

“I remember my blood sugar on my wedding day,” Price said. “Because I had a slice of cake. And it’s like, just all these ways diabetes affects moments of our lives and makes us step away from human connection, and the things that would otherwise be meaningful and joyful. That other people don’t even necessarily recognize we’re stepping away from.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.