How bad cartoons helped relieve the chronic-disease blues

When my spouse spent 48 weeks on chemo, I got markers and paper lunch bags, and tried the gallows humor thing.

Listen 5:44

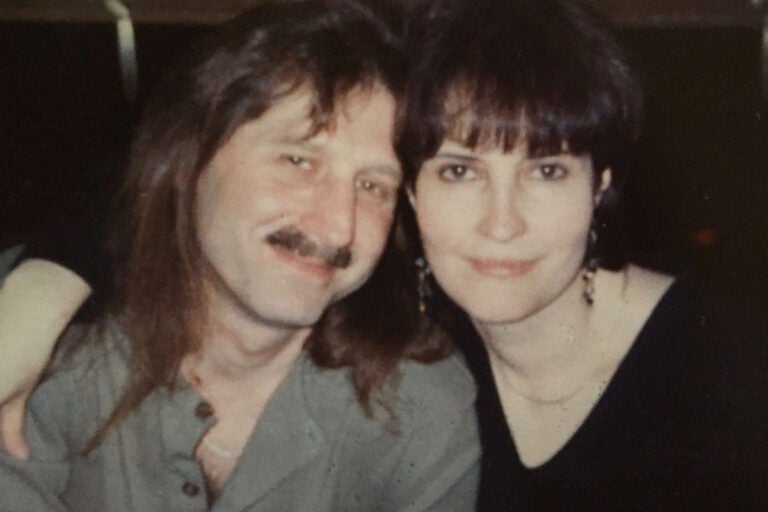

Paul Hathaway and Joanne McLaughlin. When Paul spent 48 weeks on chemo, she got markers and paper lunch bags, and tried the gallows humor thing. (Image courtesy of Joanne McLaughlin)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Chronic illness makes your world very small — like a pandemic stay-at-home order nobody else has to obey.

Life becomes so absurdly out of rhythm with the rest of the universe, you gotta laugh. Because crying every day just sucks, even when you’re not the one suffering. Trust me on this.

It was a week or so before Christmas when things flipped upside-down for my husband, Paul Hathaway, and me. I wasn’t particularly looking forward to the holiday because Paul and I were not in a good place — and that was before the night he got home from work, climbed into bed shivering so hard the mattress shook, and spent days there.

The diagnosis: a much-advanced case of hepatitis C, back in the days when no one — OK, maybe something like 40% of people — was cured of the most common form of the virus. The doctor told me the odds were better that Paul would die of natural causes, this beast could hang on that long. He was 49 years old.

So there we were, about to walk into an adventure crazy even for us — two people on the verge of divorce who had already lost $35,000 in a bad business venture. Paul, who managed and booked blues musicians through much of our marriage up to that point (see just-mentioned money-losing business), started calling his office over our garage “The Cave.” It all seemed like a bad joke.

Back in the early 2000s, before today’s boffo drug combos that cure almost everyone, the commonly used chemotherapy for hepatitis C was a 48-week-long one-two punch: One shot a week of pegylated interferon to daze the thousands of virus particles attacking the liver, and 10 antiviral pills a day to kill the little monsters. Well, unless you were among that unlucky 60% of patients nothing helped.

What the chemo did very successfully was make Paul feel like crap for at least two days after he injected the interferon, whose brand name was Pegasys (yes, like the winged horse of mythology). Paul would do his shot at about 11 o’clock Monday night and maybe emerge from The Cave sometime in the next 24 hours.

I would trundle off to work Tuesday morning; my son, Michael, would trundle off to high school. I would come home and sing to the tune of the Beatles’ “Bungalow Bill”:

Hey, Pegasys Pete,

What did you eat?

Pegasys Pete

Hey, Pegasys Pete

How did you sleep?

Pegasys Pete

“Don’t sing, sweetie,” Paul would say, and laugh weakly. So, of course, I kept singing.

If he came into the house, he’d stare at the pasta, or pizza, or whatever I set before him, but he didn’t eat it. I could tell from the contents of the fridge that Paul didn’t eat anything while Mike and I were gone either.

So I started packing his lunch every Tuesday. You know, a brown bag with a peanut butter sandwich and a Tastykake and a banana, plus a bottle of water. I’d find them on the coffee table in The Cave, untouched, when I got home.

All those drugs. Empty stomach. Bad liver. Not good.

One week, I left him a note when I dropped off the bagged lunch. He smiled wanly at me. Did he eat? Nope.

The week after that, I left him a recipe for “Paul’s Pegasys Punch” (serves one, over seven days). “Yeah, yeah,” he said, he got the joke. But did he eat anything when the chemo was at its strongest in his system? No way.

Six weeks of this, and I got serious about being funny.

Funny ha-ha

One thing to know about me: I have a great eye. I was decorating editor for years at the Philadelphia Inquirer. But I can’t draw to save my life.

Then again, I wasn’t trying to save my life, I was trying to save Paul’s. Not to mention my sanity. Why I thought cartooning would accomplish that, I have no idea.

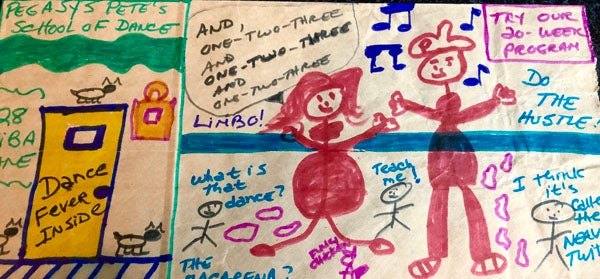

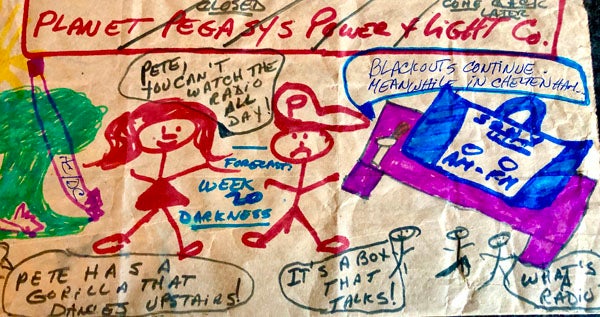

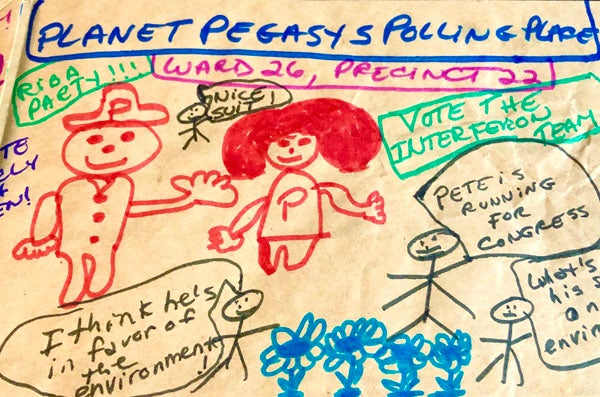

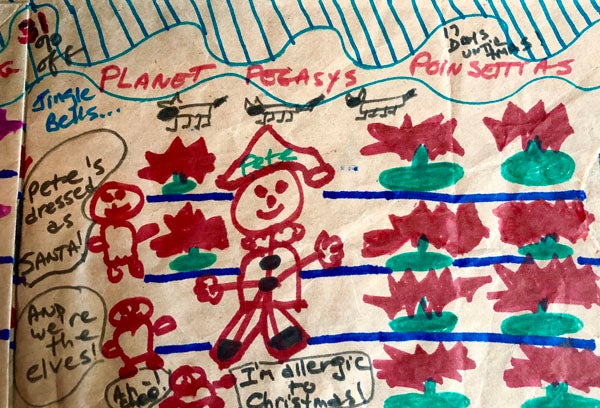

But after Week 6 of 48, I became a maker of lunch and an illustrator of lunch bags every Tuesday morning. And “The Adventures of Pegasys Pete” was born.

Week 7, I came home to find a half-eaten sandwich and a banana peel. “What, you don’t like Butterscotch Krimpets?” I remember asking. Paul muttered something unprintable.

Week 8, success again! I bought more brightly colored markers.

My illustrations were very sophisticated: Pete is a stick figure, with a hat with “P” (for Paul, etc.) on it. His partners in chemo are Mrs. Pete (moi) and Little Pete (my son, who at that point had lived with Paul for seven years and, like me, figured what the heck, what did we have to lose). Occasional appearances are made by the Pegasissies, a sort of Greek chorus of goofy commentary. (“Not peanut butter again!”)

I began to decorate Planet Pegasys (with Pegasys Posies) and populate it (with Pegasys Ponies). I made musical allusions (“Hotel California,” of course.) My comic creative juices kicked into overdrive to catch up with my fight-or-flight response.

And our lives spilled onto the bags: My son was a big skater, so skateparks were one leitmotif, as was the kitten we acquired about four months into Paul’s chemo. Mike and I went to London for his high school graduation: I left a bag to cover that week, with my version of scenes from the Underground, and Big Ben and the Millennium Bridge. (Paul ate what she put in the bag, my mother said. I never knew for sure.)

Subscribe to The Pulse

Week 20, when a hurricane took out our power, Pegasys Pete “watched” a battery-powered radio all day long.

He went trick-or-treating for Halloween, and voted on Election Day (it was appropriately, an off-year election).

By Week 30, it was December, and I drew 18 poinsettias, one for each week of chemo left. (OK, they were red things with green, close enough). Pete celebrated Hanukkah, too, the way Paul did.

Week 38 was Oscars season … and the winner was Pegasys Pete!

In keeping with Paul’s love of PBS and Discovery Channel and History Channel, Pete haggled with the experts on “Antiques Roadshow,” observed primates in the jungle, and worked with Nazi hunters.

By Week 48, I was relieved in more ways than one. Chemo was done. Paul’s appetite was back. The virus was gone — or so it seemed.

Funny strange

Paul finished chemotherapy the day after Easter, a sunny Monday in April. By Memorial Day, we knew something was wrong. By his birthday in August, it was official: His viral load was through the roof again.

Terrible times followed. He went into a profound depression, and was angry all the time. He had neuropathy and pain issues and started using Oxycontin. When he couldn’t buy enough pills, he started shooting heroin after not using for about 18 years.

We raged at each other. I locked him out of the house at least once. Then one day, I called him six kinds of a word that starts with an M, has an F in the middle, and ends with an R.

“Six kinds? Which six?” Paul asked. I enumerated them, using every curse word I could think of. He laughed, and humor defused the ticking time bomb — if only for the moment.

“Six kinds” became our shorthand for “Watch your step, buster.” If I could make him laugh, the real Paul resurfaced for a little while. Eventually, a friend helped connect Paul with a methadone maintenance program, and he tamed that beast again.

What we would discover in the six years that followed, though, was that the hepatitis C would chip away at who Paul was, even as it didn’t kill him. Some days were good, some were awful, and you couldn’t predict which would come when.

The virus ate away at Paul’s liver and his head. Hepatic encephalopathy, aka “brain fog,” results when your liver can’t clean toxins out of your body. Paul would totally zone out mid-sentence, or talk in a language that we never could identify. He fell asleep while driving. I had to get his doctors to insist that the methadone center give him enough take-home doses to cover a week, to keep him off the road. I took my vacation one Friday at a time, so I could drive him to get those doses.

He started calling The Cave by a new name, “The Hospice.” The bad joke kept getting worse.

Watching basic cable TV made us laugh in progressively more macabre ways. We’d tune in to shows about incorruptibles, people whose bodies didn’t decay after death. Lots of Catholic saints got their holy cred that way. I’d turn on the Eternal Word Television Network and make Paul watch old movies like “Miracle of Marcelino.” He’d throw popcorn at me and shout at my retreating back, “Go write a book!”

Paul was obsessed for a while with a show called “Crime Scene Cleanup.” It was research, he said, so he’d know all the things he didn’t want me to have to deal with if he decided to do himself in. He was only half-kidding.

I reminded him of all the things he should do to avoid implicating me in his death. He reminded me motive wouldn’t be an issue: He was worth as much to me alive as he was dead, because he had no life insurance.

Guns were too messy, pills unreliable. We decided if he had to do it, it would be in the car in our closed garage. The house was mostly detached from it. Our cats, he figured, would be OK.

Sounds creepy, but it kept both of us from pulling into that garage, lowering the door and leaving the engine running. If you joke about the elephant in the room, it’s just an elephant.

And that’s all it ever was. Paul died a little more than eight years after his diagnosis — in his sleep, peacefully on the couch in his office-turned-cave-turned hospice, with the TV on. Probably from a heart attack and a body too weak to fight. (His father died of a heart attack when he was 50, Paul had learned about 10 years after the fact.)

After Paul’s death, I wrote that book, a vampire novel. Its title, “Never Before Noon,” is the name of our money-losing music management business.

Somewhere, I know Paul is laughing at that one.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.