How a gene editing tool went from labs to a middle school classroom

Listen

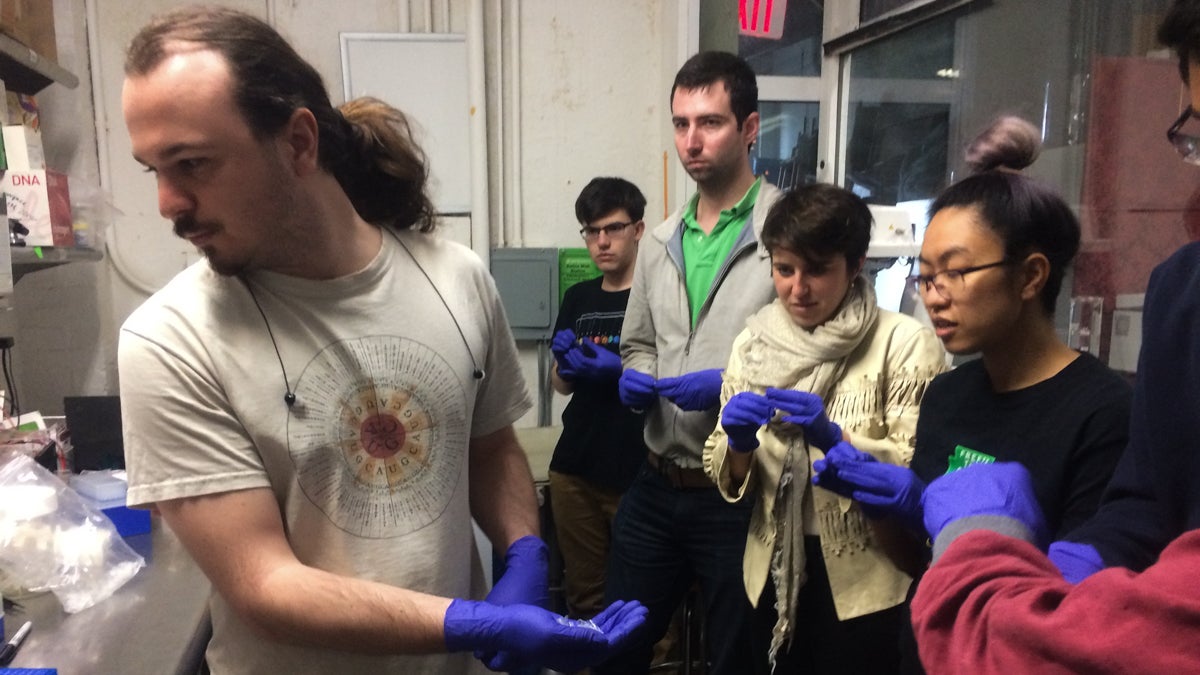

Genspace Lab Manager Will Shindel passes out pipette tips to the students while explaining their lab protocol for the day. (Alan Yu/WHYY)

It seems just like yesterday that the gene editing tool called CRISPR Cas9 burst into the science community with seemingly endless options and opportunities.

In 2015 – it was named the “breakthrough of the year” by the journal Science.

And now – just two years later – CRISPR is already expanding its reach beyond professional science labs into classrooms – and perhaps even your kitchen. You can take classes and buy gene editing kits for as little as $150; even kids in middle school are doing this.

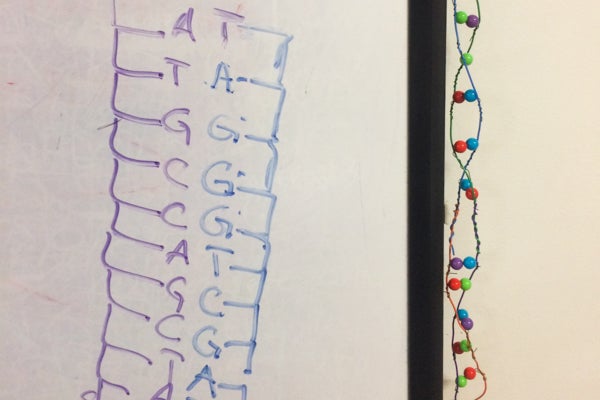

On a Saturday afternoon, I join a group of 10 students in a classroom at Genspace with tables, a whiteboard, and two strings of Christmas lights hanging on one side, twisted to form the DNA double helix.

Next to the whiteboard, these Christmas lights are twisted to form the DNA double helix. (Alan Yu/WHYY)

The students come from a range of backgrounds: a fresh graduate with a master’s in plant biology, a medical student, someone who works in pharmaceutical advertising, a high school student who started a synthetic biology club, and an eighth grader.

Lab manager Will Shindel is teaching the class. He’s been doing it for a few months, and he says the students are usually professionals who want to learn a new career skill or “everyday people who have heard about CRISPR in the news…they just know that it’s this word that everybody’s throwing around, it’s either going to lead to the singularity or the apocalypse.”

Shindel goes over the history and science behind CRISPR for an hour, then the students head into the lab to work on their assignment for today – genetically modify yeast so that it turns red.

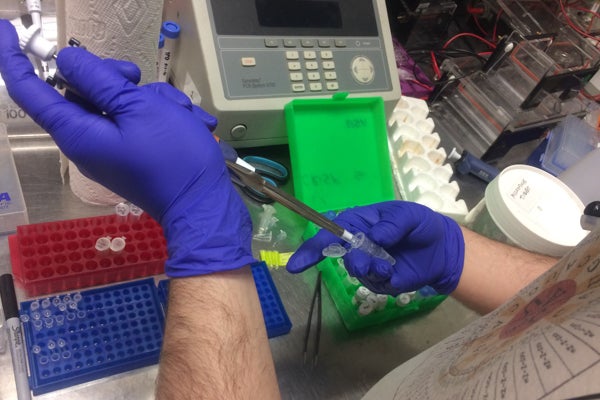

They mix different solutions with pipettes, the organisms are spread in a solution across a Petri dish, the Petri dishes go in an incubator…there’s quite a bit of lab equipment involved.

But you don’t need to be in a class like this to try it out. Some companies have put all that gear in a CRISPR kit you can buy online, which is why some middle school students at Acera, an elementary and middle school in Massachusetts, have done CRISPR experiments as well.

Abby Pierce is 13, and she recently completed one of these experiments, changing bacteria so that they can grow on a Petri dish with an antibiotic that would have killed them.

“It was kind of funny, ’cause I was talking to one of my friends’ science teachers, and she was actually really surprised that we got to use CRISPR.”

Kids at other schools are learning about CRISPR, but she actually got to do it.

Her class did these experiments using a kit you can buy online for $150, from a company called “the ODIN.” Last year, their science teacher Michael Hirsch started teaching the students molecular biology using kits from a company called Amino Labs.

He recalls one experiment, which involved leaving some bacteria to incubate overnight.

“They came in the next day, and a culture that was yellow suddenly turned red,” Hirsch says. “It’s like, ‘woah, what happened there?’ And so I think it started to click, like, ‘wait a minute, there actually is something that’s going on in there, we’re seeing science happen… I really mutated bacteria.’ And they love the idea that they mutated something.”

He says kits from companies like Amino are taking science from labs and putting it in classrooms and homes, because in the past, doing this experiment would have taken several different machines that costs tens of thousands of dollars.

“I told the folks at my school that Amino is going to do for biology what the PC did for personal computing,” Hirsch says. “It’s going to take molecular bio out of the ‘oh man, cool, they do it in labs’ to ‘wait, we can do this in our homes.’ We could do things like create pigments and create flavor extracts and all of these really nifty things safely and carefully in our kitchens.”

Although the idea of people editing genes in their homes and kitchens might sound strange, Hirsch points out sometimes it takes a while for us to get used to a technological change like this.

“If you were, 50 years ago, to say that everyone in their home would have a computer…computer manufacturers would look at you like you’re crazy.”

Now Hirsch is not the only one making this comparison. Two years ago, Joi Ito, director of the MIT Media Lab, gave a talk at the O’Reilly Solid Conference called Why Bio is the New Digital.

“You can now take all of the gene bricks, these little parts of genetic code, categorize them as if they were pieces of code, write software using a computer, stick them in a bacteria, reboot the bacteria and the bacteria just as with computers, usually does what you think it does.”

And just like with personal computing, people are now dreaming about and starting synthetic biology projects. Will Shindel, the lab manager at Genspace, is working on one with some friends.

Genspace Lab Manager Will Shindel mixes all the chemicals before class, so the students don’t have to do any math during the class to figure out how to dilute them. (Alan Yu/WHYY)

“It was just something that we blurted out over a couple of beer,” he says. “My friend and I were talking about all the different types of basil there are, there’s lemon basil, I saw seeds for chocolate basil in the store last spring.”

So – they started to dream up new addition to the basil offerings.

“What if we could give basil weird flavors? We could make vanilla basil, or spicy basil, and we were like, ‘no no, spicy basil, that doesn’t seem like a good idea, what about a spicy tomato?'”

And now Will has some tomato plants growing in the lab in Brooklyn, and his team is trying to figure how to edit their genes.

Some people are trying to make bacteria produce insulin.

That sounds exciting right?

But before we get too carried away, we have to remember that right now, bacteria are not as predictable as computers.

Kristala Prather is an associate professor of chemical engineering at MIT. Her team studies how to engineer bacteria so they produce chemicals that can be used for fuel, drugs, and other things.

She says living things are just a lot more complex than computer code.

“I have a first year graduate student that I was meeting with just last week, who was lamenting the fact that even though she has cloned genes many times before, it’s taking her a little while to get things to work well at my lab,” she says. “And my response to her is that the same is true for about 80 percent of students who come into my group.”

Prather says engineering bacteria isn’t quite like coding because there are many more variables at play.

“One of the common mistakes that people make it to assume all water is just water; the water that comes out of the tap in Cambridge is different than the water that comes out of the tap in New York, and that’s because of a number of reasons…the source of it, as well as how it’s processed…so there are very small things like that that can turn out to make a significant difference.”

Now don’t get me wrong, she’s also excited about how kits and classes are bringing synthetic biology to everyone.

“I was a 13 year old kid who had a Commodore 64 computer, and I could write my own computer programs to do all sorts of interesting things, and i didn’t really need anything other than the computer.”

She says even if all these kits do right now is get more people excited about becoming scientists, it’s still really valuable.

Now there’s one other thing: Remember what Will the lab manager said about what some people think of CRISPR?

“It’s either going to lead to the singularity or the apocalypse.”

The German government actually sent out a warning about the CRISPR kits from the ODIN, saying they found potentially harmful bacteria on two kits they tested, but it’s not clear how those bacteria got there because they did not come with the kit.

A spokesperson from the German Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety “reminded” people that if you do this at home and not in a licensed facility with an expert supervisor, you can be fined up to $54,000.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control disagrees, and said in a statement earlier this month that the risk to people using these kits is low. It asked EU member states to review their procedures around these kits.

Justin Pahara, co-founder of Amino Labs, another kit company, says there’s really not much to worry with regards to security with DIY bio or biohacking, because it’s still in a very early stage.

Pahara got a fellowship from Johns Hopkins University to work on biosecurity, and he was just at a workshop in Washington DC with people from academia, industry, and government agencies like the CDC, the FBI, and the UK Ministry of Defense.

He says generally speaking, the US and Canada have been very supportive of the DIY space.

“You have a lot more people becoming educated in the area who are possible creators of amazing technologies and what not in the future,” Pahara says. “Kind of counter this, what we see in Europe and specifically in Germany, there’s very high regulation around DIY Bio, which again, I don’t think is a security risk, but by regulating it, they’re also stifling innovation.”

Pahara says the goal of his company Amino is to teach these skills to as many people as possible, because we have some pretty big problems to solve, and the more people we can get to work on them, the better.

He says science has progressed quite a bit, but imagine how much more progress we could make if we had tens of thousands of more scientists working on these problems.

“I’m personally invested in this because my grandfather, he died of cancer when I was really young and it really affected me, and it’s been kind of my dream to solve cancer and have some of these big discoveries to prevent people…and their loved ones from harm.”

And who knows, maybe some of those scientists we need might start with classes at Genspace or learning to edit genes using a kit in middle school.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.