Honoring the 50th anniversary of a pivotal student protest in Philadelphia

It's been 50 years since a seminal student protest shaped Philly and the legacy of Frank Rizzo. Participants gathered over the weekend to remember.

Listen 2:46

Philadelphia City Council honors civil rights activists at City Hall. (photo courtesy of council member Helen Gym's office)

On Nov. 17, 1967, thousands of students rallied outside the old Board of Education building along Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. It wasn’t the first student protest, and it would hardly be the last.

But the happenings that day — now 50 years in the rearview — have lingered in the city’s collective consciousness like few other education-related events.

That’s in part because the cause that brought students out that day — increased representation for African-Americans in the curriculum and the classroom — remains. But it’s also because of how the authorities responded to the November ’67 protest, and what would become of the man who directed that response.

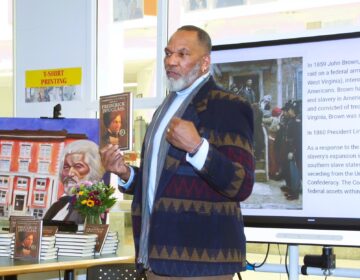

On Friday night, audience members packed a small speaking space at the African-American Museum in Philadelphia to hear former activists recount memories of that year. The turnout was a reminder of that day’s place in city lore and its enduring connection to the present.

Though much remains in dispute about that day, a few key facts are clear.

Thousands of students across the city walked out of class on Nov. 17, 1967. Somewhere between 1,500 and 5,000 of them descended on the Board of Education building. They brought with them a wide list of demands that included reforming the dress code to permit African dress like dashikis, more courses on African-American history, and a higher proportion of black administrators.

While a delegation of students was inside the Board of Education building negotiating with district higher-ups, busloads of police officers rolled up to the rally. Among them was the city’s recently minted police commissioner, Frank Rizzo.

A confrontation between police and students ensued that led to 57 arrests and scores of injuries. Karen Asper-Jordan, a 19-year-old graduate of Simon Gratz High School, recalls being dragged by an officer. Kenneth Heard, then 16 and a student at Mastbaum Technical High School, remembers “six or eight” officers charging at him and beating him. When they eventually pulled him off the ground, Heard said, he had swollen arms and a pulsing headache.

“It wasn’t the prettiest thing you’ve ever seen,” Heard said.

At the onset of the conflict, Rizzo said something inflammatory. But what exactly he uttered remains unclear.

Asper-Jordan heard the future mayor say “get their asses” in reference to the protesting students. Others recall him saying “get their black asses.”

Whatever order Rizzo barked out that day, the 1967 protest became a pivot point in his rise and a key bullet point in his eventual legacy.

Walter Palmer, a civil rights activist who helped lay groundwork for the protest and was there that day, believes Rizzo’s response to the student protestors burnished his law-and-order credentials and heightened his political profile.

“He became a folk hero to white America all across America,” Palmer said. “He had a solution in terms of how to deal with the Negro.”

But as has been reaffirmed recently, Rizzo’s actions tainted his reputation among African-Americans and led to calls of bigotry. In countless discussions of Rizzo and race, many point to the 1967 protest as an example of clear and pernicious prejudice.

Earlier this month — as the protest’s 50th anniversary approached — the city announced it would move a prominent statue of the former mayor. Many saw it as a direct response to Rizzo’s record on race relations and police brutality.

The 1967 rally, however, is more than simply a footnote in the raging Rizzo debate. It underscored the school district’s changing demographics and spurred an evolution in leadership’s attitudes toward race.

In 2005, Philadelphia became the first public school district to require African-American history, at long last fulfilling one of the protestors’ front-line demands.

But just because there’s been progress in some areas doesn’t mean the protesters see a rosy picture. Asper-Jordan believes the district has slipped since her days and laments the loss of established black teachers.

“The struggle is constant. The struggle continues,” she said. “And when you think you can sit back and relax, you find out you can’t.”

For Asper-Jordan and others who lived the 1967 protest, Nov. 17 was a formative experience. Yes, it connected to larger trends and ties nicely into the city’s political history, but their memories tack more to the personal. It taught them about right and wrong. It taught them about power and helplessness.

“You don’t forget abuse,” said Asper-Jordan. “I don’t care who does it. You don’t forget abuse.”

When Kenneth Heard thinks back on the chaos of that day, he doesn’t think specifically of what happened to him or any other individual protestor. He thinks more about just how large the melee seemed, and how many people took part. It still leaves his head shaking.

“It’s the massiveness of the brutality,” Heard said. “How do you do that to people? How do you stop a set of folk from doing it again?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.