Getting to the basics of humor for people on the autism spectrum

Many don’t perceive jokes that rely on sarcasm and dual meanings. Improv comedy can help with understanding that, and teach other life skills.

Listen 5:07

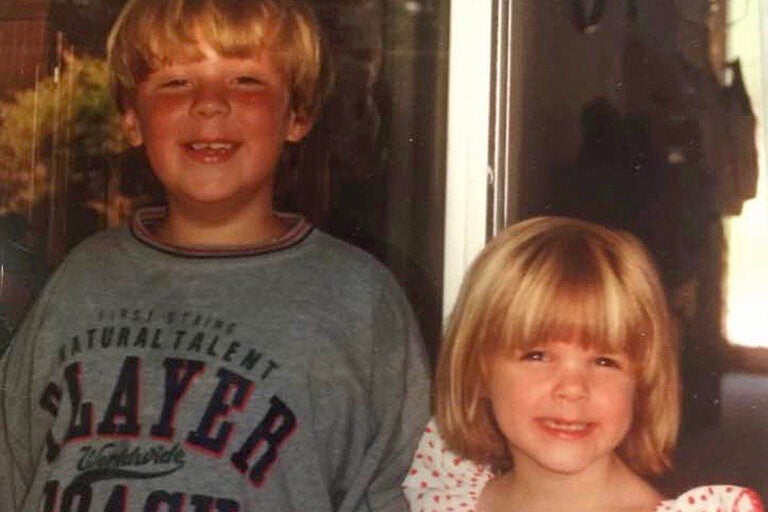

Maja Watkins, (right) at 5 years old, with brother Zachary Miletich, 7, in Danville, California, 1992. (Courtesy of Maja Watkins)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

From an early age, autism spectrum disorder has played a significant role in Maja Watkins’ life. Not only is her older brother Zack on the spectrum, Watkins is a social and emotional learning specialist who works with children and adults diagnosed with ASD.

According to the National Institute for Mental Health, ASD is a developmental disorder that affects communication and behavior. It’s largely marked by difficulty in social communication or interaction and repetitive behaviors. Autism is considered a spectrum disorder because there is a high degree of variability among the individuals diagnosed.

Growing up, Watkins experienced a number of instances where her and her brother’s communication styles didn’t always align, especially in the area of humor.

“There was a time where I was pushing him on a swing, and I think, at one point, I said, ‘Ugh, I have to stop. My arm is gonna fall off.’ And a week later, I pushed him on the swing, and he’s like, ‘Stop! Your arm is gonna fall off.’ He took it so literally,” Watkins said.

Aside from communication, Watkins and her brother also have different tastes in humor. For example, Watkins loves sarcasm while her brother prefers physical comedy.

“My husband is a standup comedian and has really beautifully written jokes that are very thought out and make whole rooms full of people laugh. My brother often doesn’t laugh at those.”

But when he watches a video of Maja’s husband skateboarding and “actually falling down and actually breaking his arm … that made my brother laugh harder than anything. Because it was shocking and different, and it was, it was like it threw him off. And it was physical and it wasn’t this intricate sarcastic thing,” she said.

Ali Arena is a board-certified behavior analyst and speech pathologist, who works with a lot of clients on the spectrum. She thinks that this difficulty perceiving sarcasm is because many people on the spectrum aren’t aware of the background information required to understand that type of humor. Another reason is that they are interpreting the statement completely literally.

“Something like, ‘Oh, my bad.’ I had to really explain that to someone. Because they were like, ‘Well, what did you do that was bad?’” Arena said.

Clinical psychologist Jason McCormick said this misinterpretation is often related to people on the spectrum having difficulty with mental flexibility.

“Most jokes have, you know, a surprise element to them, but then you also [need] things [to] hang together. So, as an example, the joke, ‘How did the hipster burn his mouth?’ And then the answer, of course, is because, ‘He ate vegan pizza before it was cool.’ So we’ve all burned our mouths on eating pizza too fast, but the surprise is that cool refers to something other than temperature. It refers more to attitude, but then that second piece is how it all fits together. So you need surprise and then coherence,” McCormick said.

However, because there is a great deal of heterogeneity among people with ASD, McCormick cautioned that not everyone on the spectrum struggles with these specific functions.

“I don’t want to paint this as autism spectrum disorder, there’s no way you can ever have a good sense of humor. But aspects of executive function can make sense of humor kind of more elusive,” he added.

Subscribe to The Pulse

The Improv Method

These moments with her brother inspired Watkins to pursue an education in early childhood development with a focus on special needs, which later developed into her lifelong career.

While working in a special-needs classroom, Watkins joined the Los Angeles chapter of Second City, where improvisational comedy is both taught and performed. She discovered that many of her newly developed improv techniques were successful in engaging her own students.

“Like I have improv games, where the goal is to make people laugh, and you have to learn how to make them laugh. And they try to keep a stone face, and not laugh. And it’s literally called Stone Face. And I’ve played that a lot with people on the spectrum, and they have epiphanies,” she said. “They’re like, ‘Oh my gosh. Me just repeating a line from my favorite tv show isn’t making this person laugh, but that would make me laugh like crazy.’ And then, they start thinking like, ‘Well, what have they done that they’ve laughed at, and maybe, it’s something different like slapstick or a silly face.’”

That realization can actually be pretty significant for people on the spectrum. Many of them struggle with theory of mind, which is basically the ability to predict someone else’s thoughts and feelings.

“So then, the children on the spectrum that I work with will do a new idea, and it will make the person laugh. And, they’ll be like, ‘Whoa, that is huge. I just went in their perspective, and it made more of an effect.’ And it’s super exciting for people on the spectrum.”

Watkins partnered with Ali Arena and therapist Nicole Moore to develop the Improv Method, a continuing-education course on the incorporation of improv comedy games into various therapeutic strategies. She also co-founded Zip Zap Zop Enrichment, a nonprofit organization providing improvisation classes to develop students’ verbal and nonverbal skills, such as self-advocacy and flexibility.

Both Watkins and Arena believe that humor can not only be a powerful teaching tool, but that it can also create opportunities to access vulnerability.

“Sometimes in improv, like, I will mess up,” Arena said. “And I’m like, ‘Ugh, I can’t actually think of a word.’ And if [my clients] like giggle at it, it’s like, ‘Oh wow. You are also being vulnerable and feeling my uncomfortableness. This is great. Like, we’re in this moment together.’”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.