Front row to American history, on a Kensington barstool

A new book about a Kensington veterans club is a small peephole onto the national stage.

Listen 5:35

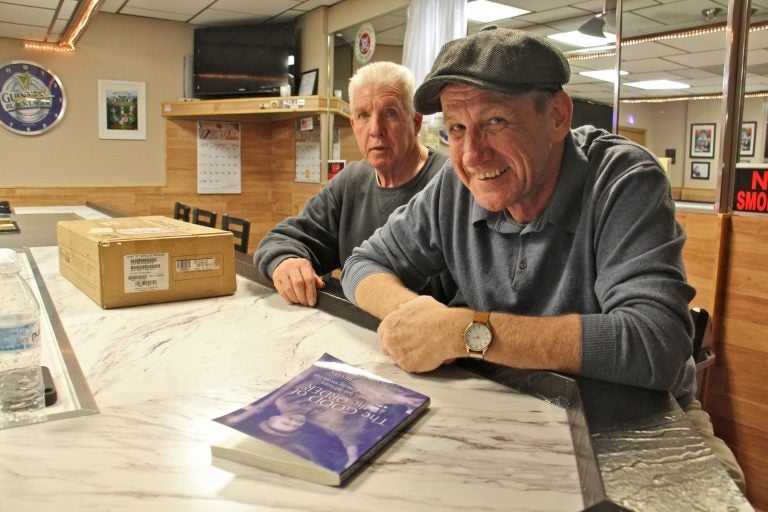

Gerard Shields (right), author of "The Good of the Order, and Edward Hepworth, steward of the AmVets club on Sergeant Street in Kensington, sit at the bar where Joe Manko recorded more than 50 years of history. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Mention Kensington to people who don’t live there, and it could evoke — on the one hand — a “hellscape” of homeless addiction and blight, or — on the other hand — a neighborhood starting to gentrify away from its working-class roots.

To the locals in the AmVets club on Sergeant Street, Kensington is the center of the world.

“This was the neighborhood beacon,” said Gerard Shields, sitting at the bar of the veterans club. He now lives in Maryland but grew up a couple blocks away. “You needed a job, you came here and asked around. If someone was sick, you raised money. If your house burned down, you’d have a fundraiser. It was a light bulb for this neighborhood.”

Shields is the author of “The Good of the Order,” a slender history of Kensington written from the perspective of AmVets Post 146. The bulk of the book comes from 360 pages of notes — a half-century of direct observations — written by Joe Manko, a World War II vet who co-founded the club in 1947 and steered its course until his death in 2005.

Manko used to come in every Saturday, sit at the bar, and take care of club business: keeping accounts, making lists, looking after its members. If somebody needed something, Manko always knew where to go for help.

“I never saw the man drink ever in my life. I knew him for 60 years and never seen him drink,” said Edward “Heppy” Hepworth, the current club steward. “Every Saturday when he came in, we would go, ‘Quiet, here comes Joe.’ Because we were rowdy when we were younger. He was quiet. Nobody knew he was writing this.”

Hepworth was clearing out shelves in the club’s basement to make room for renovations recently, and he came upon a sealed cardboard box. Inside were a set of binders filled with hundreds of pages of notes that had been carefully wrapped and stored.

Those pages were sent to Shields, who used to be a newspaper reporter. (Now he works for the Maryland Department of Correctional Services.) He was asked to put them into a book.

Shields used the notes to trace a history of the neighborhood, including the time then-candidate John F. Kennedy drove a campaign tour through Kensington. The mostly Irish-Catholic residents knew they had found their hero.

Later, the official national prayer cards for Kennedy’s funeral were printed by a nearby company.

The book describes how men would play hooky from Sunday services by going to the AmVets to hoist a few. One person in that breakfast club was chosen to run over to the church and grab a stack of bulletins to be able to take to their wives, as proof of attendance.

“That would make him listen to the homily, too, so you could tell the wife what the homily was about,” said Shields.

“It was a little rough, but everybody cared for one another,” said Hepworth. “You belonged to this place.”

Lasting lessons of confidence, compassion

The current brick behemoths that sit empty in Kensington’s landscape were once the economic envy of the world. Most everyone in the neighborhood had a job in the neighborhood, making textiles or hats or lace.

It wasn’t always the safest place to grow up. Hepworth remembers playing ball against a wall; on the other side, an open pool of acid burned rust off steel girders. A handful of lead smelters in the neighborhood scarred the environment in ways still felt to this day.

Some chapters of the book are given over entirely to Manko’s notes. They include the extended story of Patti the Pig, a St. Patrick’s Day mascot brought into the neighborhood from a farm outside the city, in the trunk of a car. The pig emphatically communicated its feelings about being trapped in the trunk of a car, paraded through the bar, and led around the neighborhood. It defecated at every opportunity.

Shields did not change a word of Manko’s original account.

Equal to the club’s epic and drunken antics were its community services. The AmVets ran a youth baseball program, a Christmas present giveaway, and street carnivals to raise money for needy neighbors.

It got away with things that would be unthinkable today —such as driving a dozen neighborhood kids down to the stadium to see the Phillies, by piling them all in the back of a dump truck.

“Today, they would have us locked up,” said Hepworth.

In the 1970s and ’80s, the club and the neighborhood felt a downturn. Soldiers coming back from Vietnam were in no mood to flaunt their veteran status. Neighborhood factories started shutting down. People left the neighborhood. The AmVets club flirted many times with shutting its doors for good.

“In the ’80s, it was the ‘New White Ghetto,’ ” said Shields. “What kept this place afloat was everybody working together.”

What makes the Kensington AmVets so relevant now, he said, is that it is a microcosm of 20th-century American history.

“These guys watched America evolve from this club, and they participated in it,” he said. “The go over to WWII and defeat the most evil man in world history. They come home, tuck their medals in the closet, and get to work making this economic force. They are part of it.”

Now, the AmVets does not sponsor a baseball league, nor host the parties it was once famous for. It’s only open three days a week, down from seven of its heyday. But it has 40 veteran members — no mean feat — and is still able to stage a street carnival to raise money for sick kids in the neighborhood.

“It was a rough neighborhood, but I never talked to anybody who wanted to grow up anywhere else on the planet,” said Shields. “This place taught them lessons and charity. It helped us so much in life. It taught us confidence and compassion. I don’t know if those are things everybody gets.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.