Diorama dilemma: The art and science of museum displays

A lot more than meets the eye goes into dioramas at natural history museums.

Listen 9:23-

The scenery in the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia were painted to be exact replicas of a real place. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

A bear inside a diorama at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

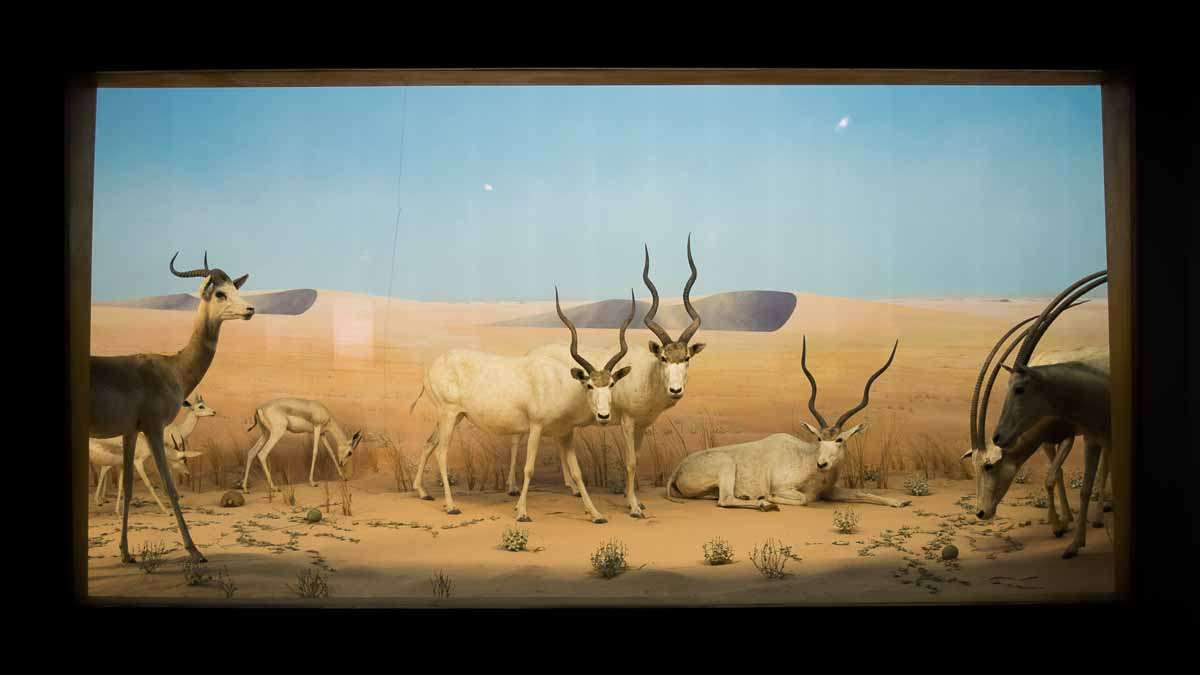

One of the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

One of the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

The North American Mammal Hall in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

A pride of lions in display in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

One of the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

One of the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

One of the dioramas at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

-

In the Mammal Hall at the Smithsonian's National Museum Of Natural History, the display looks kind of like IKEA meets academia. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

This piece is a part of our show on Natural History Museums. Take a look at the rest of our stories here.

Inside of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, Jennifer Sontchi stares approvingly at a scene frozen in time behind a pane of glass.

A puma is perched high on a boulder, crouched down and stalking a group of deer below it on the forest floor. The deer look alert, staring straight ahead with their ears perked. From the tension of the scene, you can tell what is going to happen next.

“When I look at it, I just don’t know who to root for. I want to tell the mule deer run away! But look at this beautiful cat who needs to eat and might have cubs,” Sontchi says. She’s the senior director of exhibits and public spaces at the museum. “That’s the story of nature, right there.”

This is her favorite of all the dioramas in the Academy. It’s part of the North American Mammal Hall — a long corridor lined with giant panes of glass that contain beautiful, meticulously crafted scenes. Each diorama is like a window into a different part of the world, and with just a few steps, visitors can be transported from the top of a snowy mountain to the depths of a pine forest.

They look almost like three dimensional photographs — unless you lean close enough to the glass to notice small signs of wear like dust on the animal’s eyes, or cracks spreading like a spiderweb across the background paintings. These dioramas are old and difficult to take care of. Some of them haven’t even been opened since the glass was sealed into place back in the 1930s.

Beginnings of the display

When natural history museums started opening about half a century earlier, they were essentially just a hodgepodge of taxidermied animal specimen.

“There was an ornithologist at the Smithsonian that described the first displays as, quote, ‘A perfect chaos,'” Karen Rader says. She and her colleague Victoria Cain co-authored a book called “Life on Display: Revolutionizing U.S. Museums of Science and Natural History in the 20th Century.”

That perfect chaos model wasn’t really working out for them, and as these museums started to think of themselves as public educators, they decided to make a switch.

“They realized they couldn’t put everything on display, so this perfect chaos kind of dissolved into a new tradition, which was dual collections,” Rader says.

The museums put the majority of their collections behind the scenes for the scientists, and started putting only their best stuffed critters in glass cases for the visitors. And, instead of crazy Latin names, signs had common names of the animals that people recognized and could actually pronounce.

“That was sort of the first toe in the water of making these displays more accessible. As time went on, the displays responded much more to other cultural trends,” Rader says.

It was the era of fancy department store window displays, a la “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” But instead of Audrey Hepburn staring longingly at theatrically lit diamonds on lavish fabric…imagine her staring at a chimpanzee. That would make it a very different movie.

“Department store windows, of course, looked very shiny and pretty,” Rader explains, “and this became a tradition within the museum as well. The rationale for this was that if folks are seeing in consumer culture very attractive things they want to look at, why shouldn’t the same strategy be used to harness their interest for education.”

These kinds of displays were beautiful, sure, but they lacked context. Where did the specimen come from, and what would they have looked like in the wild? These were questions the public had. And the answers to those questions came in the form of the diorama.

The diorama dilemma

A lot more than meets the eye goes into dioramas at natural history museums. Most of the dioramas are constructed as exact replicas of a precise location in the world. Scientists and artists would go to a specific location, collect specimens and start sketching, then return to the museum and reconstruct what they saw.

Scientific accuracy was a must, except for in one particular case at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Sontchi says with a laugh.

“The wonderful academy story of this moose diorama is that the director at the time looked at the moose and the diorama as it was getting put together and said, ‘I’m pretty sure these antlers aren’t quite as big as the American Museum of Natural History’s antlers. I want bigger antlers.’ So they went back into the field and got a bigger moose, removed it’s antlers and put them on our moose. I find this absolutely hilarious, because we have a Frankenmoose.”

The scientists and artists took the reconstruction of the scenes so seriously that if you look at the ground of these dioramas, you’ll see they are covered in handmade pine needles, silk leaves, and plants. That’s one of the many reasons that the dioramas are really hard to maintain.

“You can actually see in some dioramas that people who were very very well meaning had meant to come in and do something and had actually treated the ground like it was ground, and walked on it,” Jennifer Sontchi explains.

In some of the dioramas, there is no way to access the inside without removing the huge panes of glass in front of them. And even after museums sort out how to open the dioramas up, it’s a very costly process to do even the most minor repairs. Imagine how difficult it is to repair an old classic painting, then imagine if that painting was 180 degrees with a domed ceiling.

There’s concern in the field that these old dioramas can seem dusty and outdated, because of how difficult it is to spruce them up. That’s putting curators in a difficult position — they are pressured to make these museums seem relevant and modern, while still figuring out how to maintain the dioramas.

“At the American Museum of Natural History, we’re kind of a museum of museum displays,” David Harvey says. He’s the senior vice president for exhibition at what is revered to be one of the trend setting natural history museums in the country. The AMNH is perhaps best known for their North American Mammal Hall. (Depending on your generation, it may be best known to you as the backdrop for the “Night at the Museum” movie.)

The Mammal Hall is full of huge, beautiful dioramas that ironically seem really full of life. In one, a spotted skunk does a head stand to ward off a predator, and in another a pack of wolves chase a deer across a snowy field.

“It is really thought of as the Sistine chapel of diorama halls,” Harvey says.

Imagine, then, what would happen if the Sistine Chapel decided to just scrap Michelangelo’s paintings on the ceiling.

Tourism would probably drop drastically.

Instead of getting rid of the dioramas altogether like some museums are opting to do, the AMNH shelled out the cash to get theirs restored, in hopes of making them look as fresh as they once did when they were first constructed.

“The diorama is still wonderful and still amazing,” Harvey says, “but we use temporary exhibitions as a way of experimenting with new ways of thinking about the diorama…much more contemporary and up to date ways as a way to challenge and engage visitors.”

One of the ways he hopes to do that is pretty simple — just get rid of the glass.

“As we move into the 21st century, the trend with dioramas is really inclusionary. It’s really about bringing the diorama around the visitor and bringing the visitor into the diorama,” Harvey says.

Along with new technology and updating the exhibit halls themselves, Harvey hopes that the museum will feel modern while still catering to the love and nostalgia people feel for the dioramas.

Old dioramas, new magic

Back in Philadelphia, a little boy drags his parents over to Sontchi’s favorite diorama of the puma and the deer.

“Do you see this? Do you see what he’s about to do?” he asks his parents, pointing a small finger up at the puma, ready to pounce.

“He’s going to…kiss them?” his mom suggests. “They’re playing peek-a-boo!” the dad says.

“No,” the boy responds. “He’s going to kill them!” He laughs and runs to the next window, looking up at a giant polar bear standing above a dead seal.

Sontchi smiles. Even without bells and whistles, these dioramas still have a bit of magic left in them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.