Delaware Bay’s spring sex party

Horseshoe crabs breed along North America’s eastern coast, from Maine to Mexico. And every year, tens of thousands of them hook up on the beaches of Delaware and New Jersey.

Listen 07:57

When the spring high tides strike, horseshoe crabs know its time to spawn. Tens of thousands of them descend on the Delaware Bay every year for an epic mating ritual. (Steph Yin/WHYY)

It’s a night for romance at the beach here in Stone Harbor, New Jersey. Everything is swaddled in a blue satin light. The waves are liquid silver, churning and tumbling to shore.

The tide is high, thanks to a full moon. Even without headlamps on, we can see — and what we are seeing are bodies, piled across the shore, writhing in a frenzied mating ritual, right there in the sand and surf.

Alright, before your mind wanders too far … these are horseshoe crabs. They breed along the entire eastern coast of North America, from Maine to the Yucatan Peninsula. But Delaware Bay is the epicenter of it all. Every spring, tens of thousands of horseshoe crabs come here for the biggest sex party of its kind.

The creatures are most active with the full and new moons, when the tides are highest. During these times, the earth, moon and sun are aligned, creating the most extreme gravitational pull on the ocean’s waters.

A horseshoe crab looks sort of like a combat helmet meets frying pan meets extraterrestrial. They seem prehistoric, because they are. They were around more than 100 million years before the dinosaurs, and they’ve barely changed in all that time, which is why scientists sometimes call them “living fossils.” Despite their name, they are not crabs at all — they’re more closely related to spiders and scorpions than crabs or lobsters.

Multiple times throughout its life, a horseshoe crab will wriggle a soft body out of its outer shell, grow, and harden into a larger version of its former self. Through these moltings, the animals can get quite big — especially the females, which can be as long as your arm and weigh more than a bowling ball.

Horseshoe crabs have a dozen legs and 10 eyes, which, on moon-soaked nights like this one, take in lots of light. That, plus powerful pheromones emitted by the females, help male horseshoe crabs find mates.

When the spring high tides strike, the crabs know it’s time to spawn. They swim and crawl to shore, powerhouse females towing chains of male suitors behind them.

Brittany Morey, a research associate for a local nonprofit called the Wetlands Institute, said one way to tell males apart from females is that the males have a pair of modified front claws. The shape of the claw helps the males hitch a ride.

“It resembles a boxing glove, and they use that to latch onto the female’s shell,” which has a corresponding groove in it, Morey said. “It’s kind of like a puzzle.”

Lisa Ferguson, director of research and conservation at the Wetlands Institute, said the beaches in the bay are perfect for the crabs’ mating ritual.

“What they need are beaches that have a gentle slope, and a sand grain size that allows their eggs to develop,” said Ferguson. Delaware Bay has “very wide sand flats that help to temper wave intensity.”

Once the crabs have made it to shore, the females dig themselves into the sand, right near the surf, and deposit thousands of tiny green eggs. The surrounding males release their sperm, and the crashing waves mix everything together, fertilizing the eggs.

When the female is finished, “she crawls out, and the sand fills in around the eggs,” said Bill Hall, a retired marine biologist who used to work for the University of Delaware.

The horseshoe crab harvest

In the 1990s, Hall helped pioneer something called the “quadrat protocol,” a statistically reliable way to count horseshoe crabs. Around that time, they were experiencing a drastic dip in population, and scientists wanted a reliable way to monitor their numbers.

Throughout history, people have harvested horseshoe crabs. Native Americans ate them, fashioned their tails into spear tips, and used them as fertilizer for crops, a practice that became mainstream and persisted until the rise of artificial fertilizers.

What devastated horseshoe crab populations in the ’90s were two practices still occurring today: Fishers use the crabs as bait, mainly for eels and whelk, and the biomedical industry extracts blood from the crabs — lots of it.

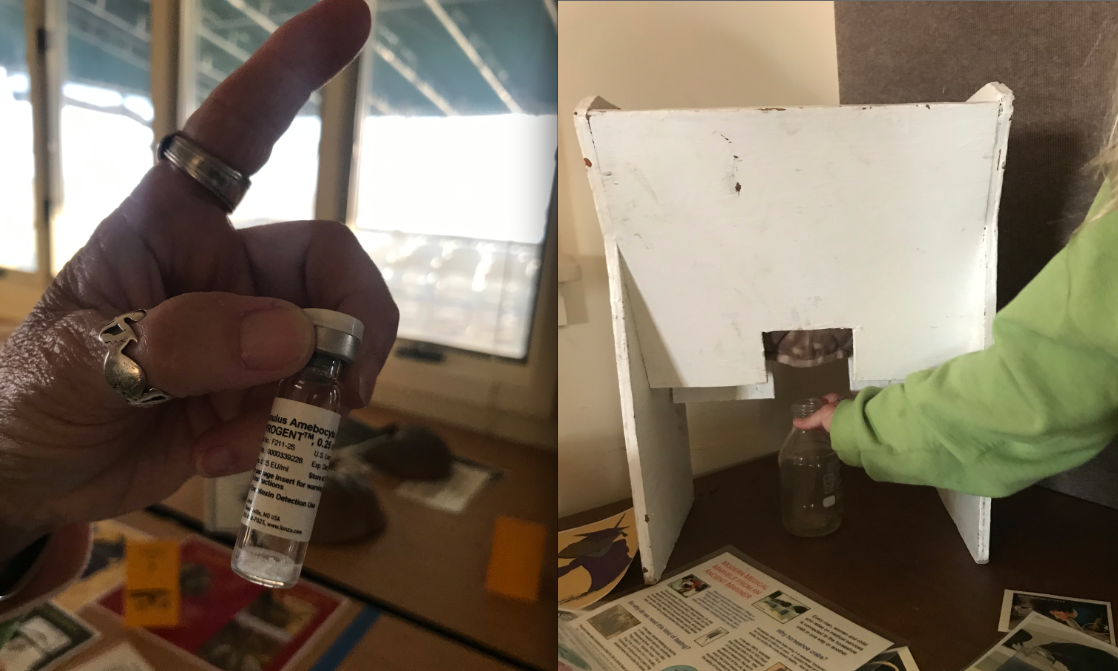

Horseshoe crab blood has a special clotting agent that forms a glob-like Jell-O when it comes into contact with bacteria. In the 1950s and ’60s, scientists realized they could use horseshoe crab blood to test vaccines, IV drips, medical implants, and anything else that might go inside a human body and therefore need to be sterile.

Just add some horseshoe crab blood to a vial, and if the solution turns to gel, that indicates there’s bacteria there.

Soon, pharmaceutical companies were collecting mass quantities of horseshoe crabs. They bleed the crabs by folding them at the soft hinge in the middle of their bodies. Plunging needles into the animals’ hearts, they pull out a blue, milky liquid — blue because horseshoe crab blood contains copper, rather than iron like human blood.

All told, the biomedical industry bleeds 500,000 to 600,000 crabs a year. They take as much as one-third of each animal’s blood, which sells for a premium price of $60,000 a gallon. Afterward, the crabs are released back into the ocean, but an estimated 10% to 30% of them die in the process.

Laura Chamberlin, who works for a conservation group called the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network, said the effects of horseshoe crab bleeding aren’t clear.

“Are the horseshoe crabs coming up to spawn the next year? Does that impact their movements? Do they become disoriented? We really don’t understand what happens,” Chamberlin said.

Ecological gold

When horseshoe crabs are overharvested, that has cascading effects. Horseshoe crab eggs and larvae are ecological gold. They provide food for fish, turtles and migratory shorebirds, including red knots, a medium-sized bird with a rusty orange face and underside, and handsome owl-like feathers on its back.

Every spring, red knots undertake an epic migration to nest, from as far as Tierra del Fuego, at the southernmost tip of South America, to the Arctic.

To fly such a long distance, the birds shrink their gizzards, the part of their stomachs that grinds up hard foods like oysters and crabs. When they stop by Delaware Bay, they get to stock up on soft, easy-to-digest, high-fat, high-protein horseshoe crab eggs. They’ll stay for 10 days, just feasting.

“They can come here and just eat nonstop,” Chamberlin said. “They double their weight, and then fly on to the Arctic.”

Red knots are federally protected and have been listed as threatened, and that has to do with the horseshoe crabs. When the fishing and biomedical industries overharvested the creatures in the ’90s, shorebird numbers also plummeted.

“They dropped the population of horseshoe crabs by 80%. Almost within a few years, the shorebird populations — particularly the red knots, but others as well, like the ruddy turnstones and semipalmated sandpipers — all dropped by close to 80% as well,” Chamberlin said. “It’s very closely linked.”

Today, there’s a moratorium on harvesting horseshoe crabs in New Jersey, and harvest limits in other states, including Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

But they are still harvested elsewhere along the Atlantic coastline, and in some of those places, surveyors “aren’t seeing as many crabs spawning anymore — they’re actually seeing a decline in populations,” Chamberlin said.

Counting, curiosity, connection

Given the horseshoe crab harvest, keeping track of their numbers remains important today.

On this particular moonlit night, as we walk down the beach, Wetlands Institute researchers Brittany Morey and Sam Collins are holding a square meter quadrat made of thin PVC pipe. Along every 10-meter stretch, they plop it down in the surf at a random point, then count and identify the sex of every crab that falls in the square. After a kilometer, we end up with 100 data points.

On our walk back to our starting point, we flip over horseshoe crabs that have become stranded on their backs or stuck behind some kind of jetty, grass, rock or rubble. If they can’t flip over or get unstuck before the tide goes back out, the crabs will likely dry out and die on the beach.

One volunteer, Megan Kately, comes out four nights a week to flip crabs.

Kately said it’s easy to feel hopeless about big problems like environmental destruction, the loss of wildlife, and climate change. This routine helps alleviate that a bit for her.

“I feel that hopelessness that we’re all feeling right now,” she said. “And I know it’s such a small thing, but then, you know, if everybody goes out and does a small thing like this — whether it’s getting rid of your plastic bags and using reusable bags, or helping horseshoe crabs — the collective effort of what that could do for the environment is amazing.”

Not to mention, she’s a bit of a horseshoe crab fanatic.

“I just see them as such resilient creatures,” Kately said. “I also like an underdog. I know that people think they are scary, or don’t like the way they look, and that’s kind of endearing to me. I feel like they have little personalities — I know that’s a weird thing to say — but sometimes they look kind of happy, sometimes they’re like, ‘Get away from me,’ and I kind of like that interaction.”

Horseshoe crabs don’t pinch or sting, she added. Although they might look menacing, the creatures are actually extremely gentle. Think of their tails as akin to rudders on a boat, a tool to help them steer in the water.

Amy Swanson, another volunteer, still remembers the magic of a field trip to the Wetlands Institute in high school. She grew up in a small blue-collar town outside Philadelphia, and had never spent more than a couple of days at the beach up until that point.

That trip was the first time she saw the night tides roll in, the reflection of the moon off the water, and horseshoe crabs. It had a deep impact, and inspired Swanson to study science in college. In the more than two decades since the field trip, she’s wanted to return.

“It just feels like my whole life has come full circle because of it,” she said. “It’s that revisiting, I mean it was 1993, ’94, when I came down. Getting to all these years later come back to something like this, it’s pretty special — it feels really nice to be able to go back to my childhood.”

All around in this group of 10 volunteers, who are in their 40s, 50s and 60s, there are many moments of revisiting childlike joy. Surrounded by the cadence of the waves, the luminous night sky, and heaps and heaps of sex-crazed horseshoe crabs, it’s easy to tap into something primordial and raw, something underneath the trappings of our modern lives.

Sue Slotterback, an educator with the Wetlands Institute, summed it up by describing a ritual she likes to do when she takes school groups out.

At the very end, she asks the students to turn off their lights, and linger at the edge of the water. “You can hear the crabs shifting back and forth, with the water coming over them,” Slotterback said.

Then she asks the students to think about the fact that, at that moment, they are witnessing something that’s been going on since before the dinosaurs were here — and will probably be going on long after we’re gone.

“Realize,” she said, “that this life that we have — to be here and see these sunsets, and see these moonrises, and horseshoe crabs, and birds flying — this is a precious thing that we have.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.