Can coronavirus ‘Victory Gardens’ quell post-pandemic hunger?

With rampant unemployment and several meat-packing plants linked to COVID-19 outbreaks, many people are turning to at-home horticulture for relief.

Listen 6:23

Neighborhood Foods Farm is a fully functioning 3/4-acre farm in the middle of West Philadelphia. This farm and a number of other community gardens produce 6,500 pounds of vegetables annually. (Image courtesy of Urban Tree Connection)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

By now, you’ve probably tried everything. Knitting, video games, dating.

In coronavirus lockdown mode, old habits die hard, and long-dead habits zombify. But even as certain areas in the United States reopen, it’s easy to imagine some of these hobbies sticking around for good.

After all, in a struggling economy, why buy a sweater if you can make one? Amid fear of the virus, why put friends at risk at a crowded concert when Travis Scott is on Fortnite?

John Jeavons asked a similar question about a now-popular activity long before lockdown: Why buy food when you can grow it?

“I asked a question in 1970. I wanted to know what was the smallest area you could grow all your food in an environmentally sound way, an equitable way, so if everyone in the whole world used that approach, or a similarly effective approach, that everyone could live well,” Jeavons said.

So he did some research and wrote a book: “How to Grow More Vegetables: (and Fruits, Nuts, Berries, Grains, and Other Crops) Than You Ever Thought Possible on Less Land With Less Water Than You Can Imagine.”

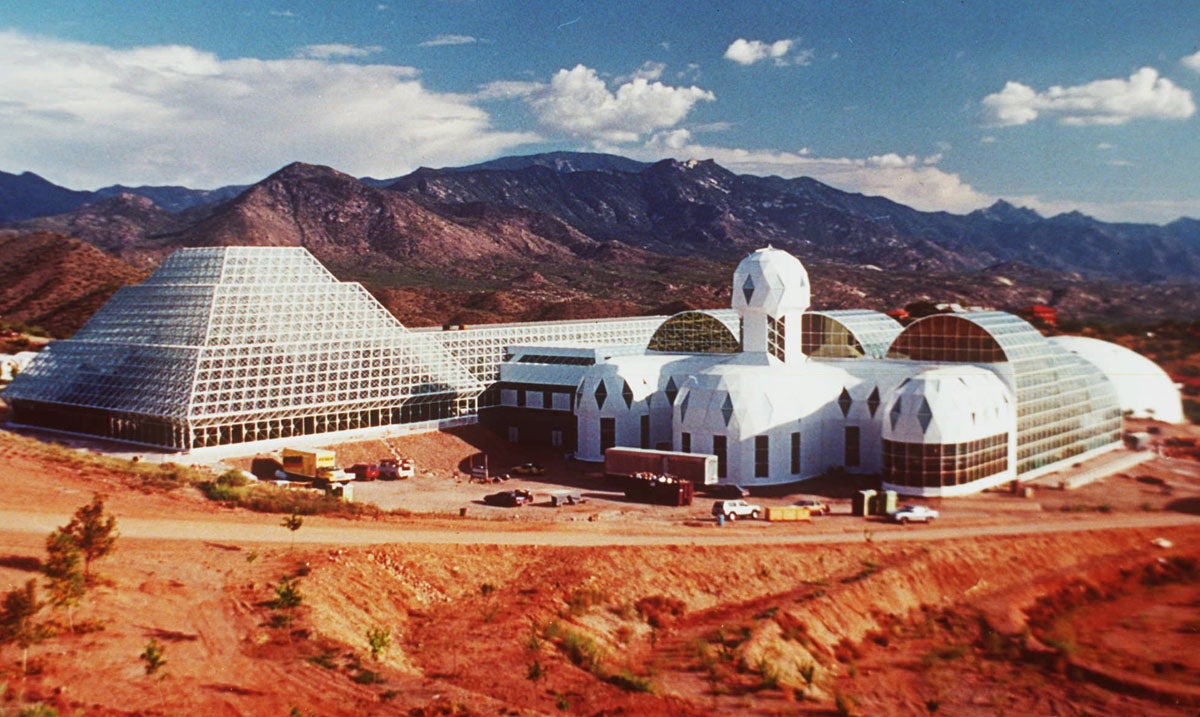

That got the attention of researchers preparing for an extraordinary experiment. They wanted to find out if humans could survive in a long-term space colony. To do this, in 1991, they sealed eight volunteers inside a large, biologically diverse greenhouse in the middle of the Arizona desert called Biosphere 2.

All the volunteers, except one, remained inside for two years. But the biospherians didn’t have much time for hobbies. They were too busy farming, largely using Jeavons’ method.

Nearly 30 years later, as online searches for “how to garden” spike and hunger looms, Jeavons hopes his method will help Americans with extra time on their hands now get a little dirty and stay full.

“There’s just no question that [the pandemic] can provide that spark to rethink how we do things,” he said.

Jeavons is the director of Ecology Action, a nonprofit in California dedicated to biointensive mini-farming, a horticultural technique originating from China that uses less land and fewer resources than traditional modern-day farming to produce more food.

As the biospherians discovered, the method is laborious. It includes digging trenches twice, planting and replanting seeds, composting and lots of focus. It all adds up to carefully selected crops planted in healthy, raised soil. That allows roots to grow deeper, rather than wider, so more calorically dense plants can be packed into smaller plots.

Still, even with all that effort, the biospherians were hungry. One lost 55 pounds. Some ate seeds meant to be planted at a later date. But ultimately, University of Arizona researchers deemed the biointensive method a success. They survived.

“There are many good principles in this practice, including building soils with a variety of complementary cover crops and providing a good balance of high-calorie crops with other vitamin and beneficial nutrient crops for diets,” said Bill Hlubik, a professor of agriculture at Rutgers University.

According to Ecology Action, the biointensive method has fed over 7 million people in 152 countries, many in the Global South, where climate change disproportionately wreaks havoc on farmers and their water supply.

“They grab on to it because it only needs local resources essentially, you don’t have to buy anything or very little, and so there’s nothing to sell. So this isn’t a product, it’s a process,” Jeavons said.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Learning some old skills

With rampant unemployment and several meat-packing plants linked to COVID-19 outbreaks, experts warn up to 54 million Americans could experience food insecurity in 2020. Many are turning to at-home horticulture for relief while questions swirl around the nation’s food supply.

“A lot more people seem to be joining the bandwagon of wanting to learn gardening.” said Hlubik, who started a webinar series with colleagues to meet the demand. Hundreds have tuned in so far. “There’s a lot of people that are experimenting that I have not seen try to even garden before doing their own landscaping. Part of it is because they’re home, I guess.”

For those starting out, Hlubik said, the biointensive method “may be a little much.”

But Jeavons argued Americans have stepped up in big ways to fight hunger before.

During both world wars, the U.S. government called on communities to plant “victory gardens” to supplement diets while rationed goods such as meat and sugar were shipped to soldiers overseas. The gardens supplied nearly 40% of the vegetables grown during World War II.

“Right now, there’s a lot of people who are unemployed and also who don’t have enough food,” Jeavons said, “So this can be used in local areas on vacant lots, on half an acre, on two acres, whatever, locally, and it can take care of providing employment, and it can take care of providing food.”

Some communities have already gotten a head start.

Noelle Warford is the executive director of Urban Tree Connection, the organization behind a 3/4-acre farm in the middle of West Philadelphia called Neighborhood Foods Farm.

“We’re seeing urban agriculture across the country just be recognized in a different way, which I think sort of sheds light to many of us who’ve been doing work for a long time,” Warford said.

The farm was built with the help of community leaders on a vacant lot in 2009. Now, it produces more than 6,500 pounds of food a year, and is still cultivating crops in the middle of the pandemic.

“In our neighborhood, there’s a 30% positivity testing rate,” Warford said. “We’re also just seeing a lot of people having to increase their caregiving responsibilities, people who have lost jobs, or people who are trying to juggle homeschooling with working. And so food insecurity has definitely been on the rise.”

With in-person distribution out of the question, the farm pivoted to meet the needs of the community, delivering its first shares of fresh produce to 64 families.

“We’re not going to return to some norm, the world that we were in before, prior to COVID-19,” Warford said, “so our work is really beyond food access. I’m really thinking about what does food sovereignty in a neighborhood look like, and what does it mean for a community to have control over the production of a critical resource like food. And I think the use of vacant land right now is critically important.”

Amid warnings of famine of “biblical proportions” spawned by the coronavirus, Jeavons hopes whatever world emerges from these unprecedented times, feeding those who are hungry will be more than just a hobby.

“One of the Ecology Action themes is transforming scarcity into abundance,” he said.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)