Appealing a public records request denial in N.J.? Don’t hold your breath

For one public records requester, the wait to have her complaint ruled on surpassed two years.

Listen 5:20

(Emma Lee/WHYY)

Maybe you want to read your town’s contract with an outside law firm. Or see police body camera footage from a recent traffic stop. Or peruse emails between a county freeholder and a lobbyist.

According to New Jersey state law, reams of public records should be available upon request. However, there are some exceptions to what can be disclosed, and sometimes the municipal, county, or state government agencies you ask for those records will deny your request.

When that happens, many people turn to the New Jersey Government Records Council, the state agency tasked with sorting out public records disputes in the Garden State.

The GRC was supposed to be the faster, easier alternative to filing a lawsuit in state court. But a review of the council’s internal tracking system shows it has a backlog dating back to 2014, tying up some cases without a resolution for years.

The council has also suffered budget cuts and staffing shortages in recent years, leaving the GRC with scant resources to handle a caseload that has mostly grown.

For residents trying to peek behind the curtain of government, the long delays and mounting bureaucracy paint a picture of a council that struggles to meet its core mission: making public entities more accountable.

“You can’t have it where somebody can be involved in something wrong, and they can defeat your ability to prove that what they’re doing is wrong by simply delaying your records request,” said John Paff, a prolific New Jersey public records requester and open government advocate.

“In this case, justice delayed sort of is justice denied,” he said.

Frank Caruso, the communications specialist and resource manager at the GRC, said the growing number of unfilled staff positions has become a burden on the agency in recent years, making it a struggle for the current workers to clear their assigned cases at a reasonable pace.

“We’re doing the job every day and trying to climb the mountain,” he said.

“Has this become a situation where we’re being looked at as lazy or that we don’t have the work ethic necessary to try and keep up? If that were the case, I would take that to heart,” Caruso said.

Lisa Ryan, a spokeswoman for the Department of Community Affairs, of which the Government Records Council is a part, said she could not speak to the decisions made under the prior administration of Republican Gov. Chris Christie. But Ryan added that “everything is on the table” under Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy when it comes to decisions about funding and staffing the council going forward.

A four-year backlog

The GRC was created through the Open Public Records Act (OPRA) in 2001, which endeavored to increase government transparency at the state and local level and to specify which records would be available to the public.

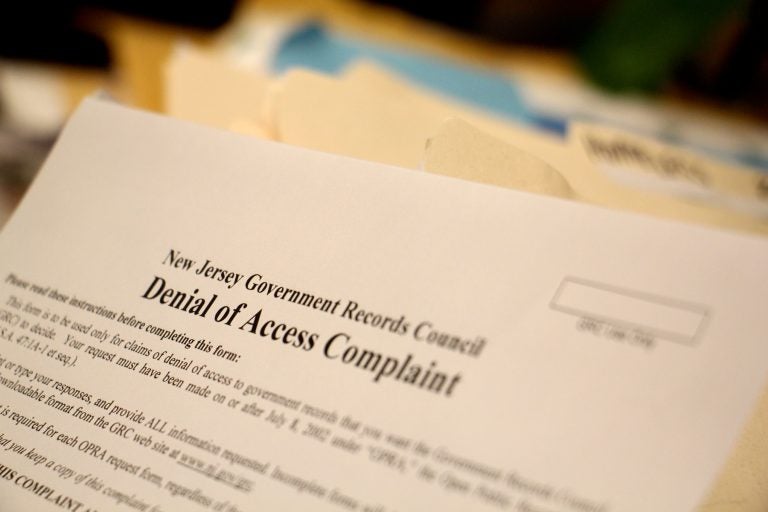

In theory, the GRC is supposed to be simpler and cheaper than enlisting an attorney and suing the government agency that denied your records request. To file an appeal with the GRC, you only have to fill out a seven-page form and send it in. The GRC does not even require appellants to appear and make oral arguments, like a judge might.

But open records advocates and residents say the GRC has morphed into something more onerous than the court system, turning what was supposed to be the easy way of appealing a public records denial into the more headache-inducing option.

“I don’t think there’s really any good reason for a person to go to the GRC anymore,” said Paff. “I used to think there was but, especially now with the delays, you really are better off in Superior Court.”

Since 2002, the GRC has received about 4,800 so-called denial of access complaints, the basic form required to file an appeal with the council.

About ten percent of those complaints remained open as of March 28, according to the GRC’s internal tracking system.

Some were under review with other government bodies, such as the Office of Administrative Law or the state courts, but the lion’s share of open cases — 347 — were classified as a “work in progress” with the GRC. The oldest ones date back to 2014.

(On top of official complaints, the GRC also responds to informal inquiries, which it’s received more than 28,000 of since 2004.)

For one public records requester, the wait to have her complaint ruled on surpassed two years.

Around Valentine’s Day 2016, Mary Sadrakula, a former Clifton councilwoman, received a call that a work crew was cutting down trees outside one of city’s elementary schools.

“It was just such a majestic setting, because next to the school is a wooded area where sometimes we see deer and wildlife,” said Sadrakula, a self-described tree hugger. “I was appalled.”

She wanted to publicly oppose the tree-cutting at the Clifton Board of Education meeting the next day, but first she had to get her hands on the board’s contract with Rich’s Tree Service.

When she arrived at the school board office, Sadrakula made a verbal OPRA request for the contract and was shown a copy. But then, according to Sadrakula, an office staffer told her she could not have a copy of the contract or take a photo of it, and then tore the copy to shreds in front of Sadrakula.

Under OPRA, public contracts are “immediate access” records, which means governments are supposed to give them to requesters as quickly as possible.

Sadrakula enlisted public records attorney C.J. Griffin, with the law firm Pashman Stein, to file an appeal with the GRC, alleging the Clifton officials broke the law.

“C.J. did warn me that it could take a while,” Sadrakula said. “I don’t believe in our wildest dreams we thought it could take over two years.”

In March, more than two years after Sadrakula’s original complaint was filed, the GRC found that the Clifton school board did not violate the law, because it released the tree-cutting contract within the seven-day window required by OPRA, even though Sadrakula received it after the school board meeting in which the panel was apparently voting on the deal.

(Clifton education officials denied that an office worker ripped up a copy of the contract and according to GRC records said they were waiting for permission from their attorney to give out copies of the document.)

“It takes forever to get anything done,” said Sadrakula, referencing the two-year delay on her appeal with the GRC. “That just allows corruption to continue and breed and grow.” She intends to appeal the GRC’s ruling in court.

Agency suffers budget, staff cuts

The lengthy backlog comes as the GRC’s resources near their lowest levels in the council’s history.

Currently the council has four staff members, but in the past it had as many as nine staff members, including five full-time case managers.

The GRC has also been lacking an executive director for four months, after Joseph Glover resigned in December.

The staffing shortages have prompted the GRC to temporarily pause the OPRA trainings it offers to municipal, county, and state employees on the basics of OPRA and how to respond to requests. Those trainings are statutorily required by the law.

The council itself is supposed to consist of five members: the Department of Community Affairs Commissioner (or a designee), the Department of Education Commissioner (or a designee), and three public members appointed by the governor. But according to Caruso, there has been at least one vacant seat on the council since 2009.

The GRC is also being funded at nearly the lowest level since its inception. This fiscal year the council got $481,000 in state funding, which is only slightly higher than the lowest amount it ever received, $467,000 in 2004. (Since the GRC’s public members serve without pay, the funding goes toward staff salaries, overhead, and other expenses.)

“We’re evaluating the GRC staffing in the midst of the new administration,” said DCA spokeswoman Lisa Ryan.

But in his first state budget, Gov. Phil Murphy, the Democrat who took office in January, proposed keeping the GRC’s funding at its current rate.

Despite the uncertain outlook, Caruso points to the GRC’s ability to maintain a 90 percent closure rate of all its complaints amid shrinking staffing levels.

“I think it really speaks to people here really coming through and accepting the extra responsibilities and the extra duties, and still trying to work toward decreasing the backlog until that time at which we can get some reinforcements,” he said.

Lawmakers have also taken note of the problems at the GRC.

Sen. Majority Leader Loretta Weinberg, D-Bergen, has been working on legislation to update the Open Public Meetings Act (OPMA), which she hopes will be ready for a June vote by the full Legislature. Part of that will include an overhaul of the GRC.

Some ideas up for consideration include increasing the GRC’s budget, adding more members to the council, and abolishing the organization altogether.

Weinberg believes the GRC is overly complex, betraying its original mission of being an easy and simple alternative to the courts. She even attended a GRC meeting and reported that “you actually couldn’t tell what was going on from the agenda.”

But Weinberg also believes that some of the problems plaguing the GRC date back to the Christie administration, on whose watch the council’s funding began to slide and staffing levels dropped.

“I think it’s not functioning well due mostly to — like everything else that’s taken place over the last eight years — understaffing and underfunding,” Weinberg said.

Paff, the open records advocate, suggested that some government officials treat public access to records as an added burden on top of their regular duties of public service. He said there needs to be an attitude shift across the entire government in favor of accountability and transparency.

“The open government, though, isn’t some sort of subsidiary thing the government has to do on the side,” Paff said. “It’s a core function of government. It’s a priority. I think OPRA makes that clear.

“The GRC doesn’t seem to treat it that way, or maybe the State of New Jersey doesn’t treat it that was as far as funding the GRC. I’m not sure what the problem is,” he added. “But it seems like the way it should work, as least according to the spirit of OPRA, is there should be sufficient resources given to the GRC where it can crank these cases out in six weeks — not two years.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.