A stem cell treatment for MS offers some patients hope. But is it hope that will last?

After more than 15 years of multiple sclerosis, a patient travels to Mexico for a risky, experimental treatment called HSCT, against her doctor's advice.

Listen 49:46

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

Last March, Jessie Flynn, 41, sat in the light-filled living room of her Syracuse, New York, home and held up her clenched right hand — or as her husband, Bobby Flynn, called it, her “claw.”

“Her hand right now is why she can’t write,” he said. “This is her natural resting position. It claws up constantly so she can’t use it, and she’s a righty.”

The “claw” was the result of more than 15 years of multiple sclerosis, or MS — an illness that had ravaged Flynn’s life and her body … and was only getting worse.

“We know that it’s progressing,” Bobby said. “She can do nothing and in five years be completely bedridden. Or we can do what we believe is best for us, and give us that hope, and work forward together in finding a solution, in doing something.”

Which was why, in less than two weeks, Flynn would be on a flight to Mexico, in search of an experimental treatment that she hoped could turn back the clock on her MS.

The treatment, called HSCT, was risky, wildly expensive, and her doctors were against it. This was a Hail Mary pass they needed to take.

“It’s like, what would you do if you’re in my shoes?” Flynn said. “Wouldn’t you go for the chance? I don’t want to hear any of the sob stories or risk factors. I’m very pumped about this procedure. I’m excited. I have hope.”

What the illness took

Flynn was in her mid-20s when the symptoms started. There was dizziness, Bell’s palsy, pain in her knees — and worst of all, she was starting to trip.

“Which was really weird for me because I had excellent balance,” Flynn said.

She’d always been athletic — a diver, a runner, and an avid kickball player — not someone who was used to tripping over her own feet. Flynn pushed for answers, but again and again, her doctors brushed it off.

And then, finally, Flynn mentioned the symptoms to her gynecologist.

“She said, ‘You need to see a neurologist yesterday,’” Flynn said. “I was freaking out because I knew that something was wrong with me.”

Shortly after, Flynn was diagnosed with MS. It was 2011, six years since the symptoms had started, which meant not only six years of unexplained pain, but six years of lost treatment.

“I don’t know how they missed it with me,” Flynn said. “It angers me and frustrates me.”

The diagnosis marked the beginning of a long, hard, painful fight — not only against her illness, but against depression, her doctors, her fears, even her own body.

Over the years, MS took more and more from Flynn — her ability to move freely, to play sports, to go out dancing with her friends. Then it started affecting her job as a high school teacher.

“I literally went from being a teacher of the year, the year I was diagnosed, to slowly being pushed out of my position,” she said.

Flynn was 33 and at the top of her game — head of her department, language arts, at the Maryland middle school where she worked, and highly rated by the administration. After she got her diagnosis, though, things changed.

“I tried my absolute best,” Flynn said. “My handwriting was slipping, and that’s very difficult as a teacher. I wasn’t given equipment that would make things easier.”

In fact, she said, it seemed as if the administration was actively trying to push her out. Instead of making her job easier with accommodations, they made her job harder. Soon, the administration started criticizing her work. She got marked down in her teacher evaluations — the same ones she’d aced the year before. Then they demoted her from department chair.

“It was just untenable for me,” she said. “I could see the writing on the wall.”

In the end, she decided to quit. It was a heart-wrenching decision.

“Teaching was everything to me,” she said. “It’s really sad not to be in education anymore.”

In 2014, with no job tying her to Maryland, Flynn moved to be with her husband. He was in the Navy and had recently been stationed in Connecticut. But pretty soon, MS blew up her marriage too.

“Nicely put, as my symptoms progressed, my marriage did not,’ Flynn said. “I asked him if he was even still attracted to me, and he said no.”

Within hours of that conversation, Flynn’s husband was packing boxes of her stuff into a truck outside. He drove her back to her mother’s house in her hometown of Syracuse, New York.

“In the end, he drops off everything on my lawn — couldn’t even face anyone, and left with my dog,” she said. “At that point, I didn’t know if it was separation, what it was. And I’ve never seen him again.”

Just about the entire support system Flynn had relied on to cope with her MS had been destroyed — by her MS. Which meant she was now facing a life-threatening illness almost completely by herself.

“I was stripped down to nothing,” she said.

Starting from scratch

After Flynn’s soon-to-be ex-husband dropped her at her mother’s house in Syracuse in 2016, she struggled to come to terms with her illness, the loss of her job, her divorce — her new life.

It was during those low, lonely months that Flynn learned about the “law of attraction” — the belief that positive thoughts can bring positive things into people’s lives.

She focused on herself. And then, close to the end of her first year back in Syracuse, Flynn made her wish.

“I said, ‘Grant me the independence to move out, to find happiness, to move forward,’” she said.

A week later, she received a Facebook notification that an old friend, Bobby Flynn, was back in town. She was excited to reconnect. They’d known each other forever — since first grade — and she had the embarrassing, endearing memories to prove it.

“He’s Type 1 diabetic,” she said. “And in elementary school, I remember him being in my classes because on your birthday you’re allowed to bring in cupcakes. And we had to leave the frosting off. And my mom always asked, ‘Do we need a Bobby cupcake?’”

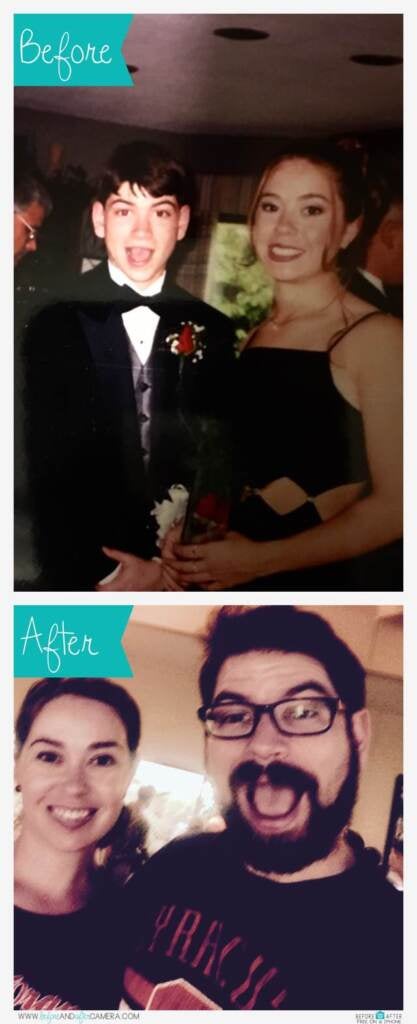

Their friendship continued into high school. Bobby had even taken her to prom their senior year.

They hadn’t seen each other in at least 15 years. But when they met up, it felt just like old times.

“It was really nice to talk to somebody who knew me prior to MS and just be real and be myself and support my new positive attitude towards life,” she said. “And the rest is history.”

Bobby proposed to Jessie in 2019 while they were on a family cruise with their parents. That same year, they got married, went on a honeymoon, and bought a house together. They even got a puppy.

After years of misery, things were finally coming together. But there was something threatening their hard-earned happiness, a storm cloud on the horizon. Jessie Flynn’s MS was getting worse.

Losing independence

Flynn’s physical therapist, Kami Palmer, started noticing her worsening symptoms in 2019.

“The last about a year-and-a-half, we started to notice a decline in her function,” Palmer said.

When they first started working together, a year or two earlier, Flynn was still pretty independent. Palmer remembers that back then, Flynn would walk into their appointments with just the help of a cane.

After a while, Flynn traded in the cane for a walker. By last year, she was being wheeled into the office in a wheelchair. At home, Jessie started needing Bobby’s help for just about everything.

“Just getting to the bathroom, getting up the stairs, getting up in the morning, going to bed at night,” Palmer said.

It was terrifying for both Jessie and Bobby — because they knew what it meant. Her MS was accelerating. And they didn’t know how to stop it.

MS is a disease that affects the central nervous system — the brain and the spinal cord. For the purposes of this explanation, let’s imagine them as a series of telephone wires. Messages travel up and down those wires from the brain and spinal cord to other parts of the body and back again.

These messages are what connect our bodies to the outside world. The central nervous system processes the data sent by our five senses, and responds with orders — orders that determine how our bodies move, whether that means gripping a pencil or raising our feet to clear a step.

To function correctly, the wires carrying those messages have to be well protected. Just like real telephone wires, our nerves are surrounded in protective insulation, a fatty substance called myelin.

What happens with MS is the immune system — for reasons that are still not understood — starts thinking of that myelin as a foreign invader and begins to attack.

Sandra Gibson, a physician assistant at SUNY Upstate Neurology who works as part of Jessie Flynn’s neurology team, describes it to her patients this way: “It’s as if your nerves are like an electrical cord, say like your cellphone charger, and you had a little mouse who came in who nibbled on that black coating on the outside of it.”

In other words, the mouse is your immune system, chewing through the myelin that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. Your body, in the meantime, tries to repair the damage.

“So what your body did is it then took electrical tape and put it around those areas to try to keep the conduction moving and going at a specific speed,” Gibson said.

You might have heard about “lesions” in relation to MS. The lesions are those damaged areas, and the scarring that surrounds them. Doctors track them using MRI scans, to see how fast the MS is progressing. New lesions mean new nerve damage, and new nerve damage often means new symptoms.

The symptoms are a direct result of how the lesions interfere with those internal telephone wires. When everything’s working well, messages from your brain and spinal cord shoot to different parts of your body in a flash. But when the phone lines start to fray — or get jammed up with electrical tape — those messages get disrupted. Slowed down. Sometimes even blocked altogether.

That can result in all kinds of symptoms, depending on where exactly the mice are nibbling. For one person, the dysfunction can start with tingling arms and legs. For another, it might be muscle weakness or spasms. You might get vertigo, double vision, trouble gripping things or speaking clearly.

In the beginning, symptoms like these came and went for Flynn. Like most people, she started out with what’s called relapsing-remitting MS, in which symptoms flare up and then disappear for a while. The goal, when treating relapsing-remitting MS, is to prevent those relapses from happening in the first place — and, it’s hoped, to slow the disease progression down.

Back when she was first diagnosed, Flynn started out with one of the usual frontline drugs, Rebif, but her symptoms continued to worsen. So her doctors put her on Tysabri — which Gibson, Flynn’s neurology PA, described as “one of our most aggressive multiple sclerosis medications.”

It’s often reserved for more advanced cases of MS, in large part because of the serious potential side effects — including a rare but severe brain infection that can cause disability or death.

But given how aggressively Flynn’s symptoms were advancing, it was a risk she was willing to take. She ended up staying on Tysabri for a full 10 years. For most of that time, the medication seemed to be working — her MRIs revealed no new lesions.

And yet, physically, she was not improving. It hit her how much shortly after she and Bobby got married in 2019. Looking back, it became clear how much functionality she’d lost — and how much more there was to lose.

“Honestly, I think it was Bobby and just being very happy with my life and looking back and noticing how badly things had progressed,” she said. “I just wanted everything to stop and be the way it was and enjoy my life.”

Flynn took a hard look at where she was. One of the strongest MS medications out there had stopped working, and she was deteriorating fast. Jessie and Bobby Flynn brought their concerns to her doctors, who confirmed their fears.

“They finally admitted to us that, yes — you are progressing,” Bobby said. “We need to do something, or else who knows where you’re going to be in a year. Five years? Ten years? When you’re faced with your own mortality, it’s just like I need to do something.”

Finding hope in a new treatment

Jessie and Bobby felt desperate. It seemed like they were out of options. But then she remembered something she’d heard about from a friend in her swim class. The friend was raising money for a treatment in Mexico called HSCT, which stands for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and, according to the friend, it could change everything. Jessie was skeptical at first, but then the friend — who was just as disabled as she was — actually got it done. And the results were nothing short of miraculous.

“This woman was basically bound to a wheelchair, and she had no mobility,” Bobby said. “She wasn’t able to drive or walk. And we talked to her a few weeks ago, and this is about a year and a half after treatment. She had driven herself to Marshalls and walked around Marshalls with a walker for an hour and a half with no problems after the treatment. So it’s hope.”

So Jessie and Bobby did some research. It turned out HSCT was a real, legitimate treatment that has had some high-profile successes. (Actress Selma Blair, for instance, said it has sent her MS into remission.)

But there were a few problems.

For one thing, here in the United States, HSCT is still undergoing clinical trials, which means, technically, it’s considered an experimental treatment. So Jessie Flynn’s health care team was skeptical.

“I felt it was my duty as her provider to be the devil’s advocate and tell her about all the potential risks,” said Sandra Gibson, Flynn’s neurology PA. “You can hear about all the wonderful things and all the promise that it can have for you. But the data still is limited. And I was a little hesitant, and I didn’t want her to get her hopes up, thinking that this would be the end-all cure-all without knowing what the potential risks would be.”

And the risks, Flynn was told, could be significant.

As you might remember, MS is caused by a defect in the immune system. The idea with HSCT is to wipe out that flawed immune system using chemotherapy, and to then build up a new, hopefully defect-free immune system by implanting the patient’s own stem cells back in the body.

“This is a therapy that has definite and substantial risks to it, because what you’re doing essentially is obliterating the person’s immune system and allowing a reboot of that system,” said Aaron Miller, medical director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis and a professor of neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York. “The immune system is required to fight off a number of infectious agents,” Miller said. “And so during the period of time, which is a few weeks while your immune system is knocked down completely and is reconstituting, you are at risk for serious infections.”

Another potential problem was that HSCT doesn’t work for everyone — which is why, Gibson said, Flynn wouldn’t have been able to take part in the large clinical trial currently being held across the U.S.

“She didn’t meet any of the criteria for any of these stem cell trials within the United States,” Gibson said. “The current trials that have happened with stem cell research involving multiple sclerosis have shown that patients need to meet certain criteria in order to have the best possible outcomes. And, unfortunately, she had progressed past that criteria. So I was concerned that she might not see as great of results as she was hoping for.”

The fourth problem was the cost. At the Mexican clinic they were looking at, HSCT can take anywhere from a few weeks to a month to complete — which, when you combine the travel costs, treatment costs, and living costs, comes out to a nice chunk of change.

“All told, we’re guessing it’ll be about $65,000,” Bobby Flynn said. “But yeah, we’ve heard ranges from $65,000 to $100,000.”

None of the above — the cost, the health risks, the doubts about whether the treatment would actually work — was enough to dissuade Jessie and Bobby Flynn.

“I have 100% chance at this point of progressing further,” Jessie said. “At least this treatment gives me some hope.”

So she and Bobby decided to go for it. They set up a GoFundMe page to raise the money, and quickly hit $50,000.

In an interview just a week before her flight to Mexico, Flynn was asked how she was feeling.

“So excited,” she said. “A little bit nervous. Very, very excited.”

Despite that excitement, she and Bobby said they were doing their best to keep their expectations in check.

“So we don’t expect magic to happen instantly,” Bobby said. “We know that this is going to be continuous work for the rest of our lives. And that’s great because it’s a challenge that we know she’s going to beat.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

The origins of HSCT as an MS treatment

The way HSCT came about — at least as a treatment for MS — was kind of an accident.

Years ago, researchers noticed that some patients with MS who had received bone marrow transplants for certain types of cancer experienced an incredible side effect.

“Their MS reversed,” said Mark Freedman, a professor of neurology at the University of Ottawa and director of the Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit at Ottawa Hospital. “And people started wondering, ‘Well, what about doing this like for real [for] their MS, not just for cancer?’”

In the late 1990s, Freedman was among the scientists who were keen to give HSCT a shot. At the time, he didn’t think that the transplants could be used as a treatment for MS. But Freedman knew that bone marrow transplants could essentially reboot patients’ immune systems — which gave him an idea. Maybe by watching patients’ immune systems reboot, they could figure out what was causing MS in the first place.

Freedman got the idea courtesy of his ’90s-era desktop computer. Every day, he’d switch it on, and watch all the little programs load before the main screen popped up.

“When we see a patient with MS, it’s like the Windows screen is open, but we don’t know how it got there,” Freedman said.

At that time, it was widely believed that MS was a purely genetic disease, which meant that, as the immune system rebooted, patients would likely get MS all over again. But as their immune systems were coming back online, Freedman thought, maybe they’d be able to observe what exactly was going wrong.

“We were fully convinced that, OK, maybe it’s not going to treat it, but this will be a reboot,” he said. “And now, rather than seeing the full Windows screen, let’s see the little programs as they load, and [that] might unveil the trip — the bad program that led to MS, because otherwise we had no idea what started the disease.”

Freedman and his colleagues collected patients’ stem cells and purified them in the lab. They then used powerful chemotherapy drugs to wipe out their patients’ immune systems, and reimplanted the stem cells to build fresh immunity.

And then they watched and waited to see when and how that bad program would load, leading the MS to return. They waited and they waited … and to their surprise, it never happened. The procedure didn’t reveal the cause of MS — but what it did was stop the MS from progressing.

“From our standpoint, from the science standpoint, it was a failure,” Freedman said. “From the patients’ standpoint, however, obviously, they were quite pleased.”

So they never figured out what exactly was causing the MS. But they did figure out a way to stop it from attacking.

“I liken this to the person who goes out and buys a car, and the air conditioner keeps going on the fritz,” Freedman said. “And you’ve taken it back 10 times, and they can’t repair it. And finally they just say, ‘You know what? We don’t know what’s wrong with the conditioner. We’re just going to give you a brand new one.’ And lo and behold, it works! And it’s something similar. We don’t know what the defect is in the immune system to cause MS, and it may well not be the same defect in different people. Our success has been on the basis of being able to completely remove the old immune system.”

Even with the incredible early results, Freedman remained skeptical. He couldn’t help but believe that eventually the MS would return.

“I kept thinking, well, it’s just a matter of time, it’s just a matter of time,” he said. “And after about five years, I went, ‘Maybe it isn’t a matter of time.’”

That’s when some of his old patients started coming in — including one with extreme vision problems due to MS, the kind Freedman said he’d never seen go away.

“I used to have to get her a special eye chart because her eyes, if you looked at them, were bouncing all over the place and they never stopped,” he said.

But as Freedman was moving to pull out the special eye chart, the patient stopped him, he said — told him she didn’t need it and started reading off the letters off of the regular chart. Freedman was shocked.

“I went, ‘Wait, hold it. What?! Are you actually reading that? How the hell…?’ And I had to look very closely,” Freedman said. “And sure enough, her eyes weren’t bouncing anymore.”

Another patient who participated in the study had initially come in barely able to walk.

“She was really quite disabled,” Freedman said. “And I saw her also around month 18, and she strolls into the clinic on high heels.” The patient told Freedman she was even going on ski trips.

Freedman and his colleagues published their results in The Lancet in 2016.

HSCT wasn’t a cure, he emphasized: It couldn’t reverse the damage that was already done. What it did was stop the disease in its tracks.

As they discovered, the rebooted immune system no longer recognized the patients’ myelin sheaths as an enemy. That stopped the inflammation, giving their bodies a chance to heal. Some patients gained functionality back. Others simply saw their disease progression stop.

More importantly, the study demonstrated that, when done properly, HSCT could produce long-lasting remission without patients needing to undergo further treatment. It also showed that it was possible to deliver this treatment without a major risk of mortality — a risk that had previously stopped some researchers from considering stem cell transplants as a treatment for MS.

Freedman and his colleagues weren’t the only ones experimenting with HSCT as a treatment for MS. Over the past few years, other researchers have also conducted studies with headline-grabbing results.

Success stories have inspired MS patients around the world to seek out HSCT. The trouble is, it’s still hard to access, even in countries like Canada and the U.K., where it’s become an accepted treatment. In the U.S., it’s primarily available only through clinical trials that are extremely difficult to qualify for.

That has led scores of patients to travel in search of treatments — including Jessie Flynn.

A month at Clinica Ruiz

Flynn boarded a plane to Mexico City on April 3. From there, she took a bus to Puebla, a city a couple hours’ drive away.

In pictures, along with Flynn’s own Facebook Live videos documenting her trip, Clinica Ruiz looks like some kind of upscale summer camp for grownups. Just about everything was right there on site: the medical facilities; the apartment where Flynn would be staying for her month of treatment; a cafe; even a roof deck, where, in the Facebook Live videos, Flynn is shown hanging out with her fellow patients.

“The whole group, we were all so excited,” she said. “Everyone was so nice, and obviously the doctors and medical staff were just amazing. I mean, you should have seen it; it was like a machine.”

Flynn even had her own caregiver, who, shortly after she arrived, offered Flynn the lay of the land.

“She had an entire calendar for me,” she said. “We sat together and mapped out the entire month.”

The first few days were dedicated to testing, designed to ensure that patients were healthy enough to withstand the treatment.

After that came two days of initial chemotherapy designed to “condition the immune system” and begin to mobilize stem cells into the bloodstream. Then came several days of shots, Flynn said, to boost her stem cell action in preparation for the transplant.

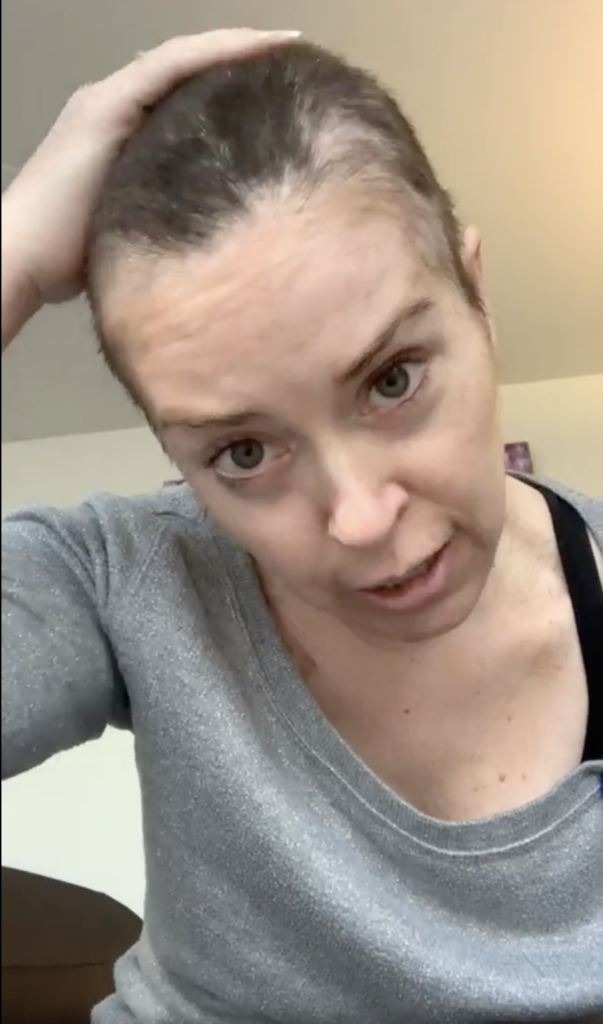

After having her stem cells collected, Flynn received another couple days of high-dose chemotherapy to suppress her immune system.

“Basically, they dock you down to nothing,” Flynn said. “We weren’t allowed to see anyone, talk to anyone, where we needed to be very isolated and careful because we didn’t want to contract any infections because we had virtually no immune system.”

Once her immune system was wiped out, they took Flynn in for her stem cell transplant. And after that, it was a waiting game to see whether and how the stem cells were able to grow a healthy new immune system.

On the whole, Flynn said, the treatment went smoothly — except for one night, after having her immune system decimated, when she got seriously ill.

“I’m convinced that I got a bad case of Montezuma’s revenge, and I spiked a fever,” Flynn said. “It was horrible. But I had an entire medical crew in my room, and they were applying cold compresses, taking my temperature every half-hour. They had to give me a blood transfusion.”

Despite that one very scary night, the rest of Flynn’s recovery went off without a hitch.

Judging the results

“I’m feeling better every single day,” Flynn said a couple weeks after her return from Mexico. “And I’ve actually seen some improvements, so I’m very, very excited.”

There was nothing huge, but a lot of little things: more mobility, less stiffness, fewer leg spasms. Even her vision was better, something she didn’t expect. The only downside, as far as Flynn was concerned, was that she had to stay hermited away for about six months until her immune system was back up and she was ready to receive all of her vaccinations (necessary since the treatment should have wiped out all of her old immunity).

Asked how the results had stacked up against her expectations, Flynn was positive.

“I mean, I had realistic expectations — I just wanted everything to stop,” she said. “That was my goal. So these are kind of like little bonuses, the improvements I’m seeing. So it’s stacked up remarkably well.”

Her husband, Bobby, said he’d also noticed improvements. In fact, the other day while he was in a meeting, he’d watched as Jessie walked to the bathroom and back with just the aid of her walker.

“She hasn’t done that in over a year, so it’s absolutely incredible,” he said. “ We didn’t have a choice, like we had to take this chance and do it, but it feels so good just seeing her get better.”

In a phone call, Flynn’s physical therapist, Kami Palmer, confirmed her improvements.

“I didn’t see any significant difference until probably about a week or two after,” Palmer said. “I noticed that, especially on her right side, she was able to pick up her right leg a little bit more.”

Flynn’s muscle spasticity wasn’t as bad, which improved her postural stability, Palmer said. She was also walking better, and wasn’t falling over when she sat down or stood up. She could do a lot more without assistance. Those improvements, Palmer said, are really big.

“It’s very big for fall risk at home,” she said. “It’s very big for her husband. He reported not having to assist her into the showers like he used to. He would have to almost, like, carry her into the shower, where now she could actually step up because her leg could bend, which is huge.”

Casting doubts on Clinica Ruiz

Neither Flynn nor her husband had any doubts about what had caused her improvements. But neurologist Mark Freedman, whose Lancet study helped boost HSCT as a viable treatment for MS, was more skeptical.

He voiced his doubts after talking with Flynn about her medical history and her treatment in Mexico.

“It’s unfortunate that it’s the same story I hear all the time,” he said. “It’s very unlikely that any objective change has occurred. But when you put 60K out of your pocket, you’re going to look for every little possible benefit.”

Freedman had several reasons for doubting Clinica Ruiz. For one thing, he said, based on descriptions of the protocol that the clinic’s director, Dr. Guillermo José Ruiz Argüelles, had published, he didn’t believe that what they were doing was true HSCT.

“This is not your typical HSCT,” Freedman said. “This is low-level HSCT. Ruiz does it because people will come down there and pay for it. He’s not what I would consider to be one of the centers that I would ever recommend anyone going to. And the procedure that he’s using is one that is least likely to produce major side effects.”

That, Freedman said, is because Clinica Ruiz uses a lighter form of chemotherapy.

“They’re certainly not wiping out the old immune system,” he said. “They’re not wiping out immunological memory.”

And that’s important, Freedman said, because the entire treatment depends on fully wiping out the existing immune system.

Dr. George Georges, a medical oncologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center who is helping to lead a major, National Institutes of Health-sponsored study on HSCT, agreed with Freedman.

“It is not a dose of chemotherapy that completely wipes out your immune system,” Georges said. “It does not completely kill off your own hematopoietic stem cells.”

What that means, Georges said, is that the next step — the infusion of stem cells — is rendered unnecessary.

“You don’t actually need the stem cell support or infusion to rescue patients from this dose of chemotherapy,” he said. “Transplanters do not consider this a real transplant.”

Freedman had another reason for doubting the efficacy of Clinica Ruiz’s treatment. Based on what Flynn had told him about her medical history, he postulated that her MS had progressed too far for it to respond to HSCT.

“We’ve had zero success, and other people have had minimal success at treating later-stage secondary progressive MS,” he said. “I think if you’ve got early secondary progressive MS, meaning you’re relapsing-remitting so much that you’re creating an accumulation of damage, those patients do well, and that means their immune system replacement may well lead to either a stopping or reversal of disease. But late-stage progressive disease with no evidence of ongoing inflammation is simply not going to benefit from this procedure.”

That, Freedman said, is why clinics like his — along with clinical trials in the U.S. — have extremely strict criteria for patients. They can’t have been sick too long, or progressed too far. They can’t be too old. They must have active inflammation, and worsening disabilities. In other words, they have to be just the right amount of sick — which is why, Freedman said, lots of patients from around the world end up traveling to places like Clinica Ruiz.

“The reason why they’re going there is because nobody wants to offer it to them in their center,” he said, “because they’re probably in this progressive stage that it’s unlikely that they’ll benefit. So they’re going to be desperate. ‘OK, well, fine. I’m going to go do something else.’”

What explains patients’ improvement?

Yet if all of this were true, why was Flynn seeing improvements?

Freedman said his best guess was a combination of wishful thinking and a drug that’s part of the clinic’s protocol — rituximab.

“They get benefit from rituximab, which is an effective medicine [for MS],” Freedman said. “I don’t know that they would benefit beyond that.”

Despite its efficacy at improving MS, rituximab isn’t formally approved for that purpose by the Food and Drug Administration, which is why it isn’t commonly used to treat MS in the United States. (Officially, it’s meant to treat certain kinds of cancer.)

Georges added that the chemotherapy could also be playing a role in why patients of Clinica Ruiz could be seeing improvements.

“They don’t need this stem cell to get the benefit from the treatment,” Georges added. “It’s just the chemotherapy that’s providing them the benefit. So that’s what’s a little bit of a sham.”

Jessie Flynn was skeptical about what Freedman and Georges had to say.

“[Freedman]’s not in a place to diagnose what type of MS I have,” she said. “His saying that there was no hope for people with secondary progressive MS, that’s false. There is less of a chance of reversal, I guess. And I have heard that, and I’ve heard that even at Clinica Ruiz. All I know is my own case.”

But Flynn also found some of their specific concerns worrying.

“It’s troubling — I don’t really know how to respond to that,” she said. “Obviously, there’s a side of me that’s kind of scared of what he’s saying is true because we’re taught to trust doctors and you know, take everything they say as truth and … it’s hard to hear things like that.”

Clinica Ruiz responds

The director of Clinica Ruiz, Dr. Guillermo José Ruiz-Argüelles, responded to questions about his clinic’s treatment over email.

Ruiz-Argüelles confirmed that the chemotherapy and rituximab were indeed responsible for the improvements patients experienced — but he said that was only because they were also responsible for a key step of HSCT, shutting down the immune system.

He acknowledged that the clinic uses less intensive chemotherapy, but said it was no less effective: “Our published results clearly prove that this diminished intensity conditioning renders similar results to high-dose conditioning.”

Ruiz-Argüelles also acknowledged that the clinic lacks the kind of stringent patient criteria of other HSCT providers — because, he said, “we have shown and published that our method renders results in all types of MS.”

But Paul Knoepfler, a professor of cell biology at the University of California, Davis who’s written about HSCT, was skeptical of the studies that Ruiz-Argüelles attached in his email response to the interview questions.

“What stood out to me about the papers you attached is the lack of rigorous clinical trial design,” Knoepfler said. “I don’t see inclusion of important features that are needed to make firm conclusions from trials about safety and efficacy. For instance, I don’t see randomization, double-blinding, or the use of placebo control in their studies.”

In response, Ruiz-Argüelles wrote: “We are not an institution supported by the government or insurance companies, so we cannot perform randomized trials as it will be unethical to offer a placebo to our patients. We are aiming to improve patients’ condition, not to show nice statistics.”

What former patients say

In emails, Ruiz-Argüelles boasted of his former patients’ outcomes, but HSCT experts Mark Freedman and George Georges complained that the follow-up contained in his studies was neither rigorous nor long-lasting enough to draw any conclusions about the efficacy of his clinic’s treatment.

One former patient who had a broader perspective than most — Caroline Wyatt, a BBC reporter in London with MS, wrote a feature about her experience getting HSCT at Clinica Ruiz.

Wyatt was in her late 40s when she was diagnosed with MS — by which time, she said, her symptoms were spiraling out of control.

“I was in a really bad way, physically and mentally,” she said in an interview. “I had double vision, sometimes triple vision, and I couldn’t speak very clearly. So I couldn’t work.”

She couldn’t even focus her eyes enough to read or watch TV. She couldn’t lift her arms. All she could do was lie in bed. Wyatt was desperate to get her life back, but nothing was working. She tried getting into an HSCT trial at a nearby hospital, but was turned away. Finally, she heard about Clinica Ruiz, though her doctor was against it.

“My general practitioner immediately said, ‘You know, there is a possibility you might die, and surely that’s not worth it to try to halt the progression of your MS.’ And I said, ‘Well, for me, actually, it is worth taking that risk if there is any chance at all that it will help me carry on working, carry on functioning.’”

After lots of research, Wyatt decided to go to Clinica Ruiz anyway — and, she said, her gamble paid off.

“I was able in those first few months to walk 10 miles a day, which just felt incredible to be able to walk up hills and at a normal pace, she said. “To get my balance back, to get my concentration and focus back so I could read again. I could follow stories. I could remember plots, I could remember names. It was amazing. And that was the most fabulous feeling.”

In the interview, Wyatt was told about Freedman and Georges’ critiques of Clinica Ruiz — that what is being done there isn’t “real HSCT.”

Wyatt — who’s done extensive reporting on both HSCT and cutting-edge MS treatments — responded that there’s a whole debate over whether HSCT must fully destroy the immune system in order to work.

“I think there is definitely a belief among some scientists that that is the way to go if you can, but then you would probably be excluding a lot more patients from that because of the need to be well enough and fit enough and healthy enough to have that done,” she said.

In fact, Wyatt said, that’s one of the reasons why she chose Clinica Ruiz. At her age, and with how fragile she’d become, she wasn’t sure she’d be able to handle a treatment that completely wiped her immunity out.

As for the notion that only patients in certain stages of MS can benefit from HSCT?

“It is still an emerging area of science,” Wyatt said. “I think the jury is still out as to exactly who is the ideal patient for which sort of HSCT.”

Wyatt added one other shade of gray to the conversation: She said that the different stages of MS aren’t as definitive as you might think. There’s no one test that says whether a patient has remitting-relapsing MS or a progressive form of MS, which is important because patients’ diagnoses determine what treatment they receive or are even eligible for.

“It’s a disagreement among different neurologists,” she said. “And I bet you anything, if you ask 10 neurologists, you will get 10 different opinions on it.”

In other words, Wyatt said, none of these rules is as clear-cut as you might think. The proof is in the pudding — meaning actual patients’ actual results.

For Wyatt, the results have been mixed. She started out feeling good, but the following year was filled with ups and downs.

“My problem came as the immune system started to recover,” she said.

Three or four months after returning home from the treatment, Wyatt could feel the fatigue coming back, along with the weights on her legs.

“A lot of people call it the rollercoaster of recovery,” she said. “And I had a horrible feeling as time passed that I wasn’t on a rollercoaster. It was only going one way, and that the MS was coming back. And I would say that, you know, the treatment helped for at least a year or two. But after that, the MS started coming back full tilt.”

Now, five years later, Wyatt said, a lot of her symptoms have returned. She reckons she’s about in the same place she was just before going to Mexico. And she’s heard the same thing from other former patients on the older end of the scale, though a lot of the younger ones have continued doing well.

Still, when it comes to Clinica Ruiz, Wyatt said she has no regrets.

“Without that treatment, I am sure I would have just carried on going downhill,” she said. “It gave me a break from going downhill, certainly for a period of months and possibly longer, because I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t gone to Mexico.”

Wyatt has continued following emerging treatments for MS, and said she’s about to participate in a study to try out a hopeful new drug — something she said she might not have been able to do if she hadn’t bought herself the last few years.

Beyond that, she said, at least for a time, the treatment gave her her life back.

“The return of enough cognitive ability to make radio programs, to present a weekly program, to do all of that and still have just about enough energy to have a life,” she said, “that is precious beyond words.”

Six months later

In the nearly six months since she returned from Mexico, Jessie Flynn said, she’s continued seeing improvements.

“I’m doing fabulous,” she said. “ I’m thrilled that I did the procedure. I only wish I did it sooner.”

Clinically, her results have been mixed.

In her first neurology appointment since receiving the treatment, Flynn scored better on some measures, worse on others.

“By the specific things that I can measure, I would say that she has gotten worse,” said neurology PA Sandra Gibson. “With the items that I cannot measure, specifically her pain level, how she feels, she feels she’s better. So from a very objective standpoint, I’d say she’s worse, but subjectively, she feels better.”

But there’s a lot that can’t be measured — and mindset is one of them.

“I think mindset is absolutely huge for patients with MS,” Gibson said. “One of the favorite phrases that I use with patients is you have MS; MS does not have you.”

Flynn has also continued improving in her physical therapy — and even her right hand, the “claw,” is better than before.

“It’s still there, but it’s a lot less spastic,” Flynn said.

Her husband, Bobby Flynn, said he doesn’t need to pry her fingers apart and put them around things anymore.

“She can wash her hands, she can wash [her] face on her own,” he said.

The other day, he said, Jessie even went outside on her own and started planting flowers — something she never would have done in the past.

“I can see a different level of confidence in her,” he said. “I’m not worried about her falling or needing my help, which is really cool.”

One other thing that’s changed since Jessie Flynn got back from Mexico — the way she thinks about the future.

“I feel like I have a future now,” she said. “I have a new goal, and that is to get back in the classroom within two years.”

Bobby has no doubt that it’ll happen — rather, that Jesse will make it happen. After all, it was less than a year ago that Jessie first decided to get HSCT.

“I remember waking up on New Year’s Day and she was like, ‘You know what? I’m going to get it,’” he said. “And then it happened almost instantly. OK. Yep. This woman knows what she wants and she goes out and gets it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.