South Koreans prepare for rare family reunions with long-lost relatives in the north

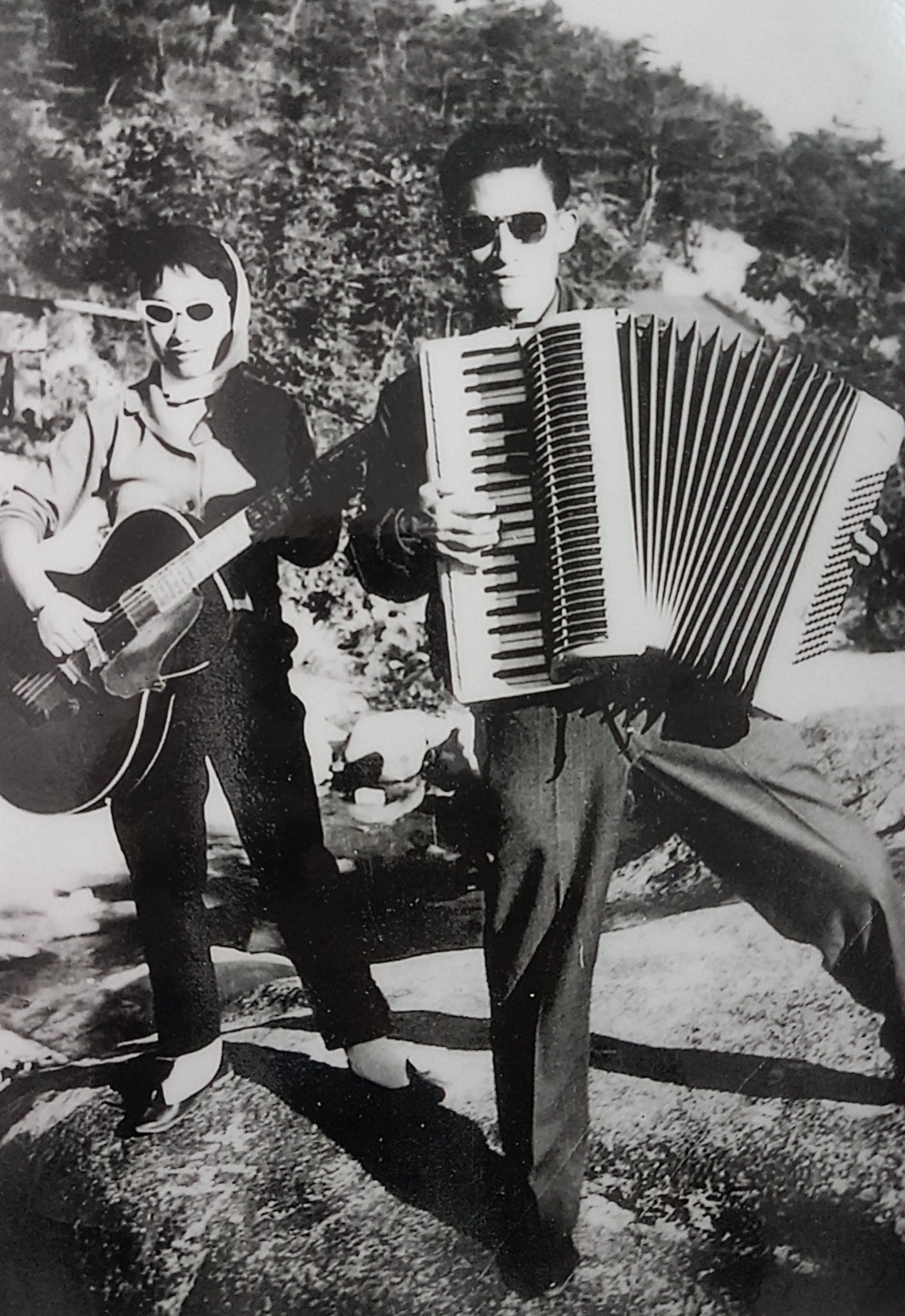

Ahn Seung-choon was 14 when her 17-year-old brother was taken away from the family home in Pyeongchang. "After that day, we didn't hear anything about him," Ahn says. (Michael Sullivan/NPR)

In August 1950, 14-year-old Ahn Seung-choon was still asleep at home early one morning when her mother woke her up, screaming that her 17-year-old brother had been taken by North Korean soldiers.

“Someone took your brother, and you are still sleeping!” Ahn recalls her mother shouting. Her mother had tried to chase the boy and his abductors, but she had babies to take care of at home and couldn’t follow them for long.

“After that day, we didn’t hear anything about him,” Ahn says 68 years later in Suwon, a city south of the capital Seoul.

The summer of 1950 marked the start of a brutal three years for Ahn, now 82, and millions of other Koreans caught up in a war that involved the U.S., China and the United Nations. The Cold War conflict left more than 3 million Koreans dead, wounded or missing.

Amid fighting, Ahn and her family fled their village near Pyeongchang; she was wounded in a bombing as she and her mother and siblings crossed a mountain pass.

“In the evening, I came to my senses, smelling shells and blood and bleeding from my own body. I went around looking for my mom, calling her,” she recalls. She saw bodies everywhere, covered in blood. “Then I saw a baby crying on the back of a body that was missing a head. I went closer and saw it was my baby sister on my mom’s body.”

“I should go see him before I die”

Ahn, who survived the war along with an 11-year-old sister, went on to marry and have six children. She never stopped wondering what had happened to her brother. Some 30 years ago, she went to her county office in Jecheon, southeast of the capital Seoul, and put her name on a list of other Koreans wanting a chance for rare, short-term family reunions granted intermittently since 1985.

Of 132,000 South Koreans who registered with the government since 1988, some 57,000 are still alive, hoping to meet their long-lost loved ones before it’s too late. No more than 100 South Koreans are given the opportunity to take part in each reunion. There have been only 20 reunions since 1985, the last of which took place in October 2015.

Now, with relations improving between North and South Korea in recent months, the two sides are reviving the cross-border reunions. Ninety-three South Koreans will board buses on Monday to meet their long-lost loved ones in Mt. Geumgang, North Korea.

As the decades passed, Ahn pretty much forgot about her own request — until she got a phone call earlier this month. She’d been chosen in the lottery to visit her brother in the North.

She was thrilled. But two days later, Ahn got another call. Her brother, it turned out, had already died. But he had left a family, and his wife and son were willing to meet.

“It hurts to know that my brother has died. It makes me sad I will never be able to see him now,” she says.

But she’s decided to go ahead with the trip anyway.

“I should see my nephew. I should go see him before I die. My brother’s son would be the only son in the fourth consecutive generation of our family,” Ahn says. She has five sons of her own, but believes family line can only be continued from father to son. “He is my father’s descendant and will carry on my father’s lineage,” she says. “So I’m thankful for that.”

“Like asking for the moon”

In a neighborhood near the Seoul National Cemetery, Yoon Heung-gyu, an energetic 92-year-old calligrapher, bounces around his basement studio, proudly showing off his karaoke machine and disco light. Like Ahn, he will be traveling north this weekend. He’ll see relatives he left behind in Chongju, which he fled in 1948, before the war began.

“When the Communist government came in, it seized our house. My family was rich and had a big house, but they kicked us out, put us in a small hut,” he says. “At the young age of 22, I hated the Communist Party. So I fled by night, alone.”

Yoon left behind his mother and a younger brother and sister. He traveled light.

“I had to flee with nothing, not even a picture,” he says. “If you get caught with something like that, it gives away that you are escaping to the South.”

He says his mother begged him not to go, but both were sure that they’d see each other again soon. Only three years had passed since the country was divided along the 38th Parallel. Like many Koreans, they didn’t think the division would last. That was 70 years ago.

“If I had known that my family would remain separated for this long, I would not have crossed the border,” he says.

Yoon married, joined the South Korean army as a military policeman and fought against the Communists during the war, all the time wondering what had become of his mother and his siblings. He registered for the reunion program almost 20 years ago, then pretty much gave up — until he got a phone call earlier this month to come meet his younger sister.

“I wasn’t expecting it to happen,” he says. “There are still more than 50,000 people waiting to meet their families. How could I be selected as one of 90-something people going this time? It was like asking for the moon,” he says.

He knows his mother died in 1973. He doesn’t know what happened to his brother, but hopes his sister might have answers. He’s also hoping his sister brings pictures showing the family together — and that he can keep his composure when they meet.

“I will have to see if I cry or not,” he says. “I will only find out when the moment comes. Meeting siblings is different from meeting my mother and father. If my mother and father were alive and I could see them, I would burst into tears.”

He is frustrated at having waited so long. “It would be good if more people can go meet their families,” he says. “But North Korea is worried that its regime might collapse if more people from this liberal country contact more people living under the dictatorship. That’s why they’re reluctant to hold more reunions.”

“I thought it was a miracle that he’s still alive”

Kim Gwang-ho, 80, will also be meeting family this week. He also wants more reunions — quickly, he says.

“One of the South Koreans going over this time is over 100 years old, I hear. How much longer will they live?” he asks. “Over 50 percent of them are in their 80s or older. If reunions don’t happen fast, they will never be able to meet their families.”

Kim, a retired professor of medicine, will be meeting his younger brother, whom he left behind in the northernmost Hamgyong province in 1950, when he fled with his father and his older siblings. Like Yoon, he didn’t say goodbye or bring any family photos with him. He thought he was just leaving for a few days, that the South Korean army would beat back the North, and then everything would return to normal.

“Of course I regret it now,” he says, “but everyone around us said there was no need to go through the trouble of moving the entire family, including the little children, since we would return shortly after. So only the five of us who were big and healthy enough to move fled.”

He and his brothers eventually built lives in the South as doctors and businessmen. They didn’t talk about the mother and brother they left behind.

“Even when we gathered together, we didn’t bring that up,” he says. “I think everyone just kept it in their minds because it’s not a happy memory … so everyone just held it in.”

But Kim did add his name to the registry, hoping to find answers. When he got the call that he’d be traveling to meet his younger brother this week, “I was surprised and very happy,” Kim says. “What was especially surprising was how could he reach the age of 78 in North Korea? The older brothers I came to the South with all died before they turned 60. So I thought it was a miracle that he’s still alive there.”

Kim says he and his brother will have too much to catch up on in too little time — they’ll be allowed to meet for just three days. He hopes they’ll have more opportunities in the future. The recent thaw in relations between the two Koreas could hasten that process, but he’s seen thaws before followed by chills. He says there’s no way he’ll waste time talking politics with his brother — even if it were allowed.

After living for 68 years in the South, Kim says, “There’s a saying, ‘Home is where you open your heart to.’ I live in Seoul. Seoul is my home.” The South Korean capital is where he got married and raised three children.

Kim’s brother, just 11 when they parted, has since married as well. On Monday, Kim will get to meet his sister-in-law too. Kim says he hopes, but isn’t sure, he’ll recognize his brother after all this time.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))