Could bringing back Wilmington High help fix school inequities?

Why a system intended to integrate Wilmington's public schools led to less diversity — and why some think reopening a traditional public high school could help.

Listen 13:08

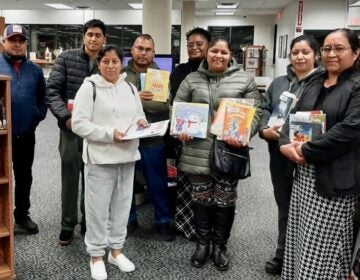

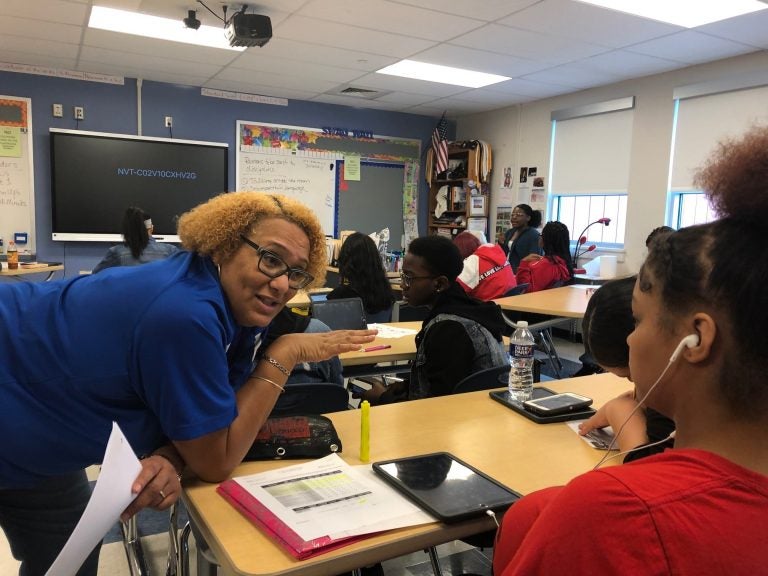

Ronda Laws teaches math at Howard High School of technology, a vocational school in Wilmington, Del. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

Listen to The Why wherever you get your podcasts:

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Stitcher | RadioPublic | TuneIn

By Cris Barrish, Mark Eichmann

Tune in to WHYY-TV on Friday, Feb. 21 at 7:30 p.m. for “Where’s Wilmington High?”, a documentary about the unique challenges for education in the city. To watch the full documentary online, click here.

—

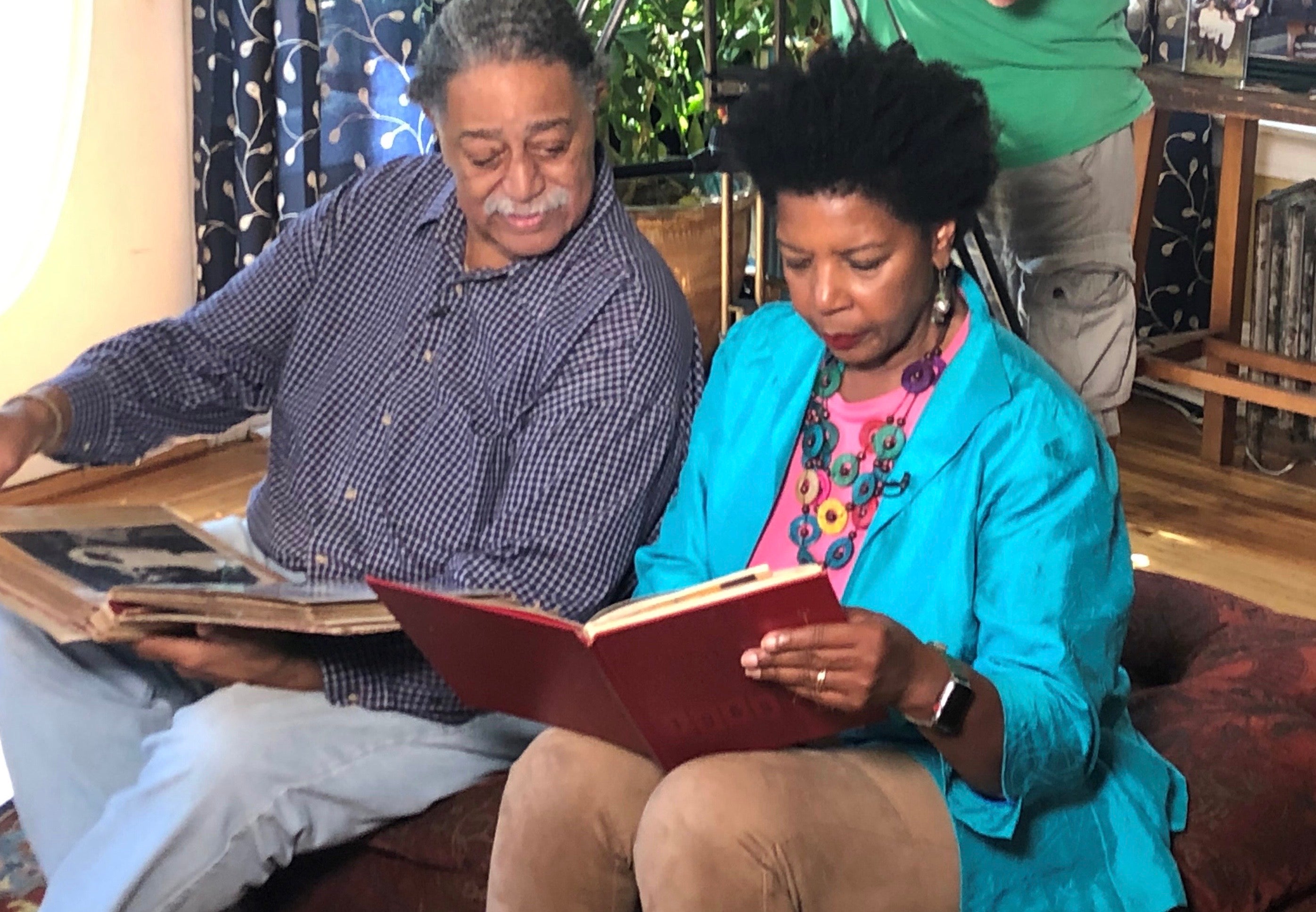

Tina and Rick Betz met as freshmen at Wilmington High School in 1965 and have been together since.

They still cherish their days as Red Devils at the city institution once known throughout Delaware as “High School.”

The couple recently flipped through their yearbooks, revealing a student body that was racially and ethnically diverse.

“It was about 50/50 and that was something that we were very proud about,” recalled Tina Betz. She and her husband are African American.

“Many of the neighborhoods were mixed. I know Hilltop where I grew up was a mixed neighborhood,” she said. “Italians and Polish and African Americans were probably the three largest minority groups.”

Jerry Clifton, a white classmate of the Betzes, agreed. “It was really a unique high school because long before diversity became a buzzword, we were diversified and we loved that idea.”

When the Betzes graduated in 1969, there were three traditional public high schools in Delaware’s largest city.

Their own beloved Wilmington High, on the west side of town.

P.S. duPont High, a grand structure on the north side.

And Howard High, originally the only high school Black children were allowed to attend, on the east side.

All were steeped in history and beacons for their neighborhoods.

Today, however, there is no traditional public high school in the city of 71,000. There are charter, magnet, private and vo-tech schools, but a comprehensive public school that accepts all students in grades 9 through 12 is not an option.

Today, most Wilmington students are bused to high schools in the suburbs that struggle academically.

Many residents, parents, students and political leaders say that makes no sense for a city that’s home to 1 in 14 Delawareans.

State Sen. Tizzy Lockman, who co-chairs the Redding Consortium — a legislatively created group looking to improve educational equity and outcomes for northern New Castle County students — says one item under consideration is the rebirth of a traditional high school in Wilmington. The consortium is studying the viability of such an idea.

“We have high schools that don’t welcome all students,” Lockman said. “A comprehensive school is a school that welcomes everyone who is assigned to that school and offers something for every type of student in that school and I think that is incredibly valuable.”

Tina Betz thinks it’s long past time to have city students once again attend their own Wilmington High.

“The fact that kids are not able to be educated where they live is a problem,’’ she said.

Wilmington Mayor Mike Purzycki, who can’t set district or statewide education policy, is nevertheless trying to help guide the future of Wilmington education from City Hall.

“I really believe that there’s a great argument for the return of a traditional public high school to Wilmington,” Purzycki said. “There’s a great argument that will appeal to the people in the city, and equally there’s a great argument that will appeal to people out in the suburbs.

“And I’ve looked at it for years and I say, ‘This can’t be right.’ But now you’ve got to turn over the whole system order to fix it and that’s a problem. It’s a challenge. It’s a heavy lift.”

A legacy of forced busing, school choice

How Delaware’s largest city ended up without a comprehensive public high school is a story rooted in racism and the fight for civil rights and access to equal opportunities for Black students.

It encompasses forced busing and the balkanization of city schools and students among multiple districts. And the government-endorsed rise of charter schools and school choice.

A primary reason for the court-ordered busing in 1978 was to create racially integrated schools for city students whose schools in the Wilmington School District had become overwhelmingly Black.

However, many education advocates argue that the results have been spotty at best.

Today, more than 2,000 of the city’s poorest students ride buses as far as 15 miles to high schools in four districts that each contain a section of Wilmington, state data show. They go to Newark, Christiana, Glasgow, McKean and others that are overwhelmingly Black and Latinx and don’t meet proficiency standards.

Meanwhile, many of the brightest and most talented students in New Castle County come into the city, where they get a top-rate education in the building that once was Wilmington High.

Dorrell Green, who took over last year as superintendent of the Red Clay School District, which serves part of Wilmington, is well aware of the disparities.

Before joining Red Clay, Green headed the state Department of Education’s fledgling Office of Innovation and Improvement that had targeted Wilmington for assistance. He is also a former assistant superintendent of the Brandywine School District, which also includes part of Wilmington.

Asked about the state of education for Wilmington students of all ages, Green said, “It’s in flux. It’s one that you’ll find pockets of success and high quality, good quality education, but it’s few and far between.

“When you look at the disproportionate number of children and families who are coming from high-poverty communities, high-trauma communities, and end up going into schools where they’re the microcosms of the schools and neighborhoods they serve.”

Green is one of hundreds of parents, students and academic, political and civic leaders who have been pondering how to fix these problems for years.

Lockman says the Redding Consortium’s mission is to create a system that works for all students.

“A strong public school system is critical for our country and for our state and certainly for our city to be healthy and functional, and I’m committed to figuring out what the next version of that looks like,” Lockman said. “Because not having a healthy functional school system that works for everyone is not an option.”

Brown v. Board of Ed, riots and white flight

To fully understand what led to the demise of the traditional public high school in Wilmington, one must dig deep into the past.

Until the middle of the 20th century, Delaware law mandated that schools be “of two kinds, those for white children and those for colored children.”

In Wilmington, where one of three Delawareans lived in 1950, Wilmington High and P.S. duPont High were for white children.

Black children went to Howard High.

But in 1952, a Black girl from the rural Hockessin area wanted to attend the nearby white elementary school. In addition, several Black children from Claymont, a few miles north of Wilmington, wanted to go to Claymont High.

Lawyers led by Louis L. Redding — after whom the consortium is named — sued to admit them and Vice Chancellor Collins J. Seitz made history when he ruled that the white and Black schools were unequal. Seitz decreed that the segregated system was unconstitutional and must be overturned. The state fought the decision but the Delaware Supreme Court upheld Seitz.

The Delaware case became one of five in the Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed school segregation in America.

Though there was opposition by the state and local districts, schools gradually integrated.

But in 1968, when civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, “everything just blew apart,’’ former Wilmington Mayor Jim Baker recalled.

Like many other cities across America, demonstrations turned to riots and widespread fires and looting in Wilmington.

The chaos led then-Gov. Charles L. Terry Jr. to call in the Delaware National Guard, which remained in Wilmington for nine months. That remains the longest military occupation of any U.S. city since the Civil War.

At the time, Baker worked in Wilmington for VISTA, the domestic Peace Corps, and became instrumental in trying to defuse the tension during what he called a terrible time.

“The National Guard came in. You had the police and all of this going on day after day after day,’’ he said. “Oddly enough, crime went up the whole time the National Guard was on the street. They are not police officers. They can’t solve that kind of problem, really.”

The Betzes graduated from Wilmington High in 1969, a year after parts of the city literally went up in flames. She called the riots a “turning point” that allowed festering issues to “bubble up from beneath the surface.”

The Betzes’ classmate, Chuck Hayward, was student council president at the time. He said students mostly hung together, even as the city frayed and ripped apart.

“One of the things that I think that made us successful, even as the riots were taking place, we had all kind of grown up together, so it was, ‘Keep that stuff out there. Here we’re in school, we’re doing the school stuff.’”

The riots and military occupation helped accelerate a drastic demographic change in Wilmington, triggering so-called white flight.

In 1950 about 15% of Wilmingtonians were Black.

By 1970, 44% were Black.

Today, the figure is 58%.

Wilmington’s population has also plummeted — from 110,000 in 1950 to 71,000 today. And schools that had been racially mixed became overwhelmingly Black.

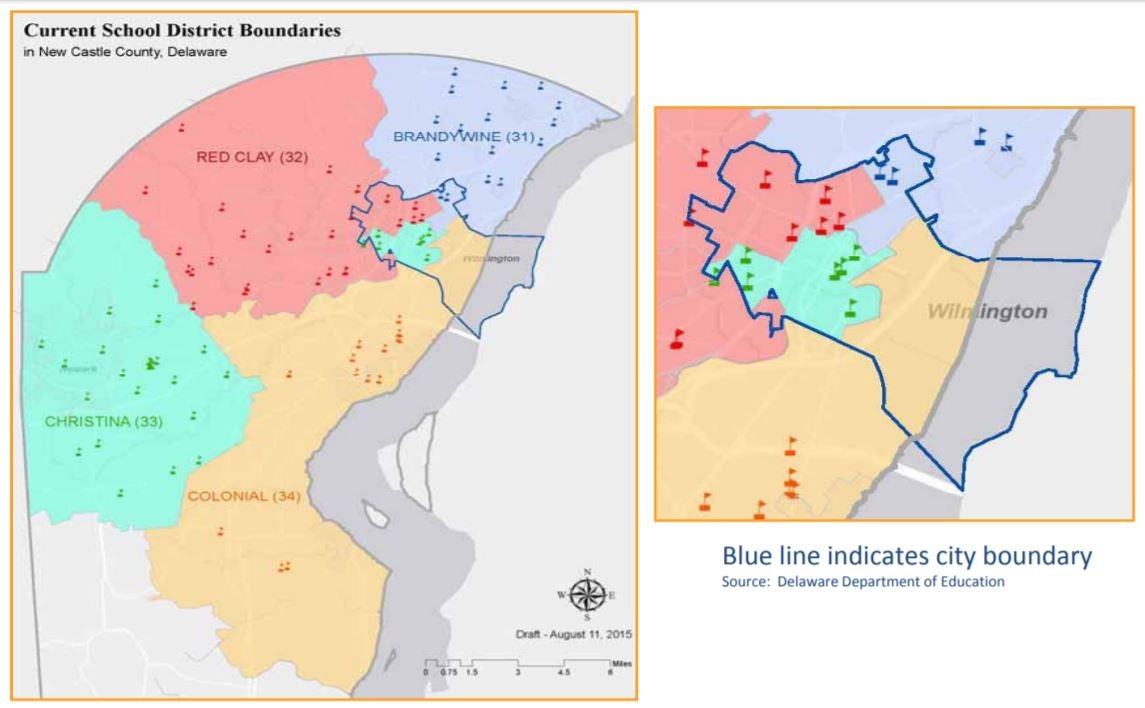

Wilmington students split among four districts

During the tumultuous year of 1968, Delaware’s General Assembly also passed a law that further isolated Wilmington.

“The law held that Wilmington — any school district with more than 12,000 students — could not be consolidated,” said Leland Ware, a University of Delaware public policy professor.

“That had the impact of separating Wilmington from every other school district” and ensuring de facto segregation.

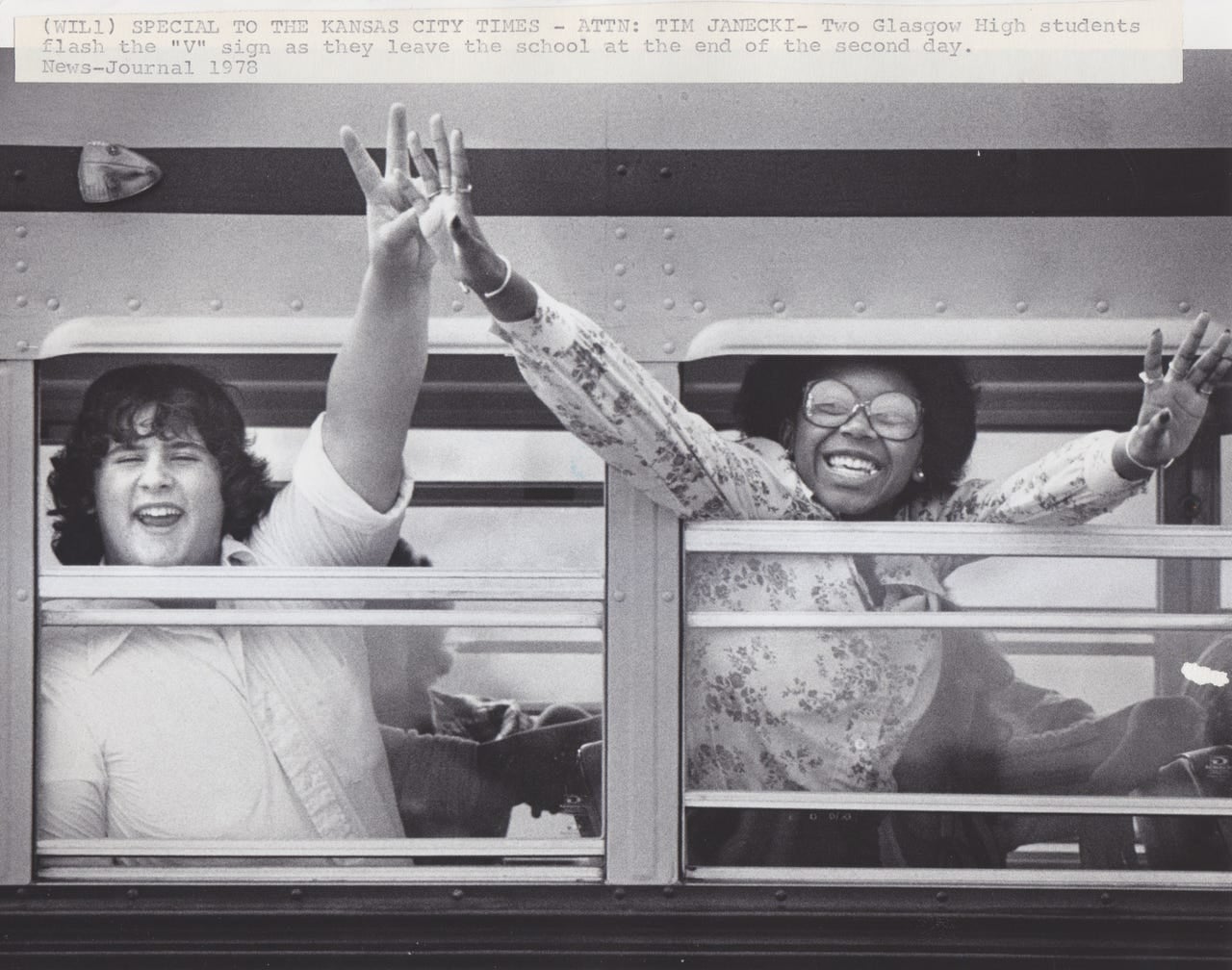

But in 1978, another lawsuit on behalf of city children led a federal judge to order a way to achieve equality in terms of race and resources: the forced busing of Wilmington kids to the suburbs for nine of their 12 school years and suburban kids to the city for three years.

Education leaders ultimately merged the overwhelmingly Black and low-income Wilmington School District with several suburban districts and created four mostly white suburban districts for northern New Castle County: Red Clay, Brandywine, Colonial and Christina.

“But part of Wilmington was in each of those districts,’’ said Ware, who has written extensively about the court-ordered desegregation plan. “It was like a pie and the idea was to avoid having one sort of inner-city school with a low tax base and poor students and lack of resources, so that was intentional.”

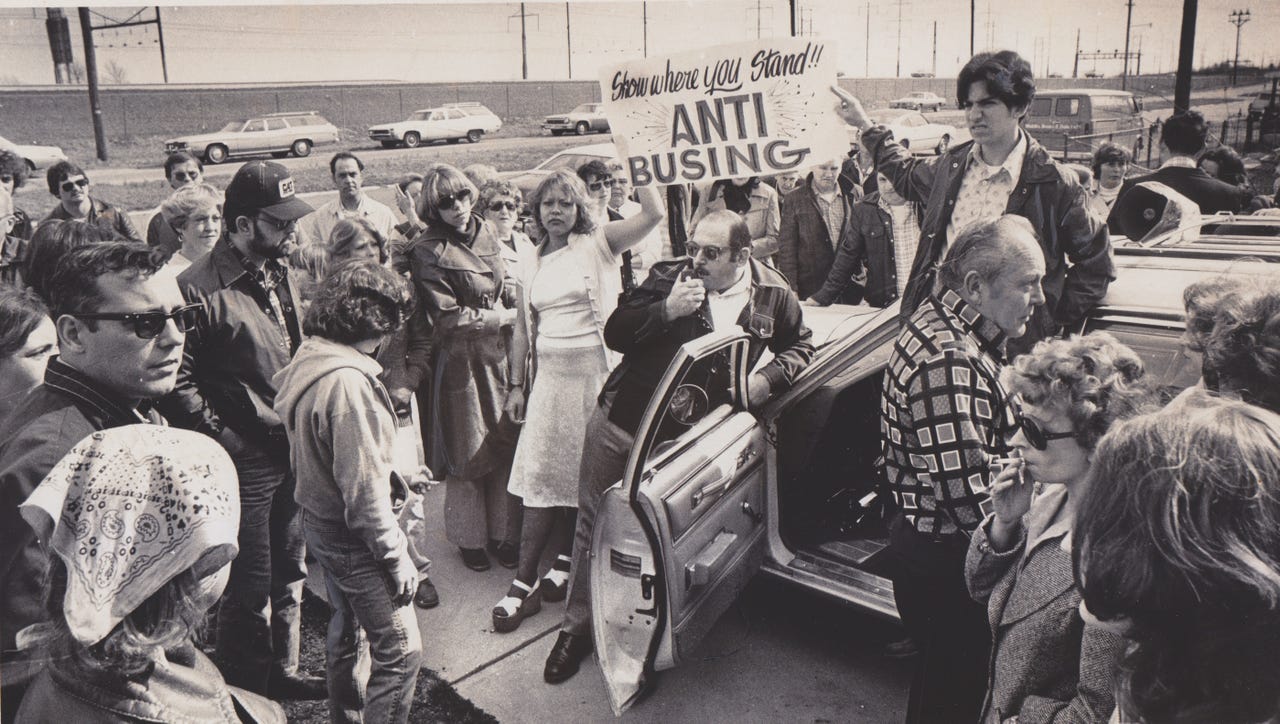

Baker, by then a Wilmington city councilman, was part of a group that opposed forced busing.

“Busing had nothing to do with education. It only took one person or a group of people from one place to another, back and forth,” Baker said. “It didn’t change education, didn’t set up a standard and in a lot of cases, didn’t deal with the kids coming into a new situation because when the African American kids came into these schools, they were still the minority.”

However, the desegregation rulings forever changed Wilmington’s secondary school landscape.

Howard became a vocational high school.

P.S. duPont joined the Brandywine district as an elementary school.

Wilmington High remained open as part of Red Clay, but city students who weren’t assigned there piled on buses bound for schools several miles away.

Erica Dorsett was in elementary school then. She says city kids bore the brunt of the burden because they were bused nine of their 12 years of school.

“I guess you could say we did provide diversity for the school, but it would also be a disservice because true busing would be to bus Wilmington students into the suburbs and bus suburban students into Wilmington [for equal amounts of their 12 years in school],” she said.

“That would be true educational diversity. That would be to me, it would show there was an effort to make sure that each student could benefit from a quality education.”

Ronda Laws, who now teaches math at Howard, recalls being one of the few Black students at Newark High before busing.

“I lived in Newark and students were bused from Wilmington into Newark and I met a lot of people I would have never met,” Laws said. “Friends I would have never had if it wasn’t for deseg.”

She acknowledged her first year was difficult.

“It was something new. It was a change,” she said. “But by the time I graduated, it was wonderful.”

Most suburban residents didn’t like the change in the status quo, or the idea of sending their children into Wilmington in the early hours of the morning, Ware said.

“They were frightened,” he said. “They felt that the city was unsafe and then there was of course the racial issues they had about their children attending schools with Black children.”

Ware said Wilmington families were divided on the issue.

“Some of them saw busing as an opportunity to attend equal schools and get the same resources and not to have to attend these low-income, racially isolated schools,’’ he said.

“But the other half, the other portion in Wilmington, African Americans, did not like their children to be bused two hours away to be mistreated, which they were, in suburban schools, and they said, ‘Look we can educate, we should be allowed to educate our children in our schools.’ And those feelings persisted, I would say into today.”

Rick Betz thinks the decisions of the past, regardless of their intent, has led to a system that’s hopelessly broken.

“It’s not going to get solved overnight, next month, next year, and it’s just not going to happen in our lifetime,’’ he said. “We’re going to see it get worse. How could it get better? Where do you start?”

Excellence at former Wilmington High, but at what cost?

Wilmington High closed in 1999, in part because of declining enrollment, but its name remains emblazoned on the building that now houses the high-achieving Cab Calloway School of the Arts and Charter School of Wilmington.

Charter of Wilmington and Cab Calloway are perennially among Delaware’s highest-rated public schools. Almost all students go on to college, many to Ivy League institutions.

Charter of Wilmington stresses math and science. Cab Calloway is a middle and high school where kids major in digital media, music, art and dance.

While Cab Calloway and Charter of Wilmington shine, they choose who gets in and have enrollment waiting lists. Teachers clamor to get jobs there.

Only 8% of the more than 1,900 students at the two schools are from Wilmington, and less than 3% are Black, Latinx or multiracial from the city.

“What I’m seeing is that they are picking kids who have had access to excellent education at elementary and middle school level. And they’re able to just capitalize on that with surely some great opportunities that they are able to offer, but they are not serving the city child,” said education advocate Tatiana Poladko, who heads TeenSHARP, a nonprofit that provides an after-school and weekend academic boost to children of color trying to get into elite colleges.

Senior art major Rodney Woodland is one of the 17 Black Wilmington residents who attend Cab Calloway. Woodland lives at 24th and Market streets, a high-poverty section of northeast Wilmington that’s been plagued by gun violence.

Woodland attended Wilmington’s Warner Elementary, where only about one in 10 students are proficient in math. Almost all students are Black or Latinx.

But a Warner mentor noticed that Woodland liked art and enrolled him in classes and camps. And since middle school, he’s been at Cab Calloway.

Woodland said the scholastic experience and life lessons he’s learned there have been transformative.

“This school made me who I am,’’ Woodland said. “Who knows who they are at 12 years old and here I am at 18, 19 and I’m who I am. I’m going to college because of the school. They’re providing me resources. It’s definitely a blessing.”

But unlike Warner and most other schools in Wilmington, Cab and Charter are overwhelmingly white in a city where nearly 7 in 10 residents are Black or Latinx.

Students ‘trying their best to succeed in the system’

A school that matches Wilmington’s demographics is Red Clay’s McKean High. Mckean’s about 10 miles from Wilmington, but one in five students are city residents, almost all are Black or Latinx.

McKean’s performance is the opposite of Cab and Charter. Fewer than one in four Mckean students are college ready or up to speed in English. Only 5% are up to par in math.

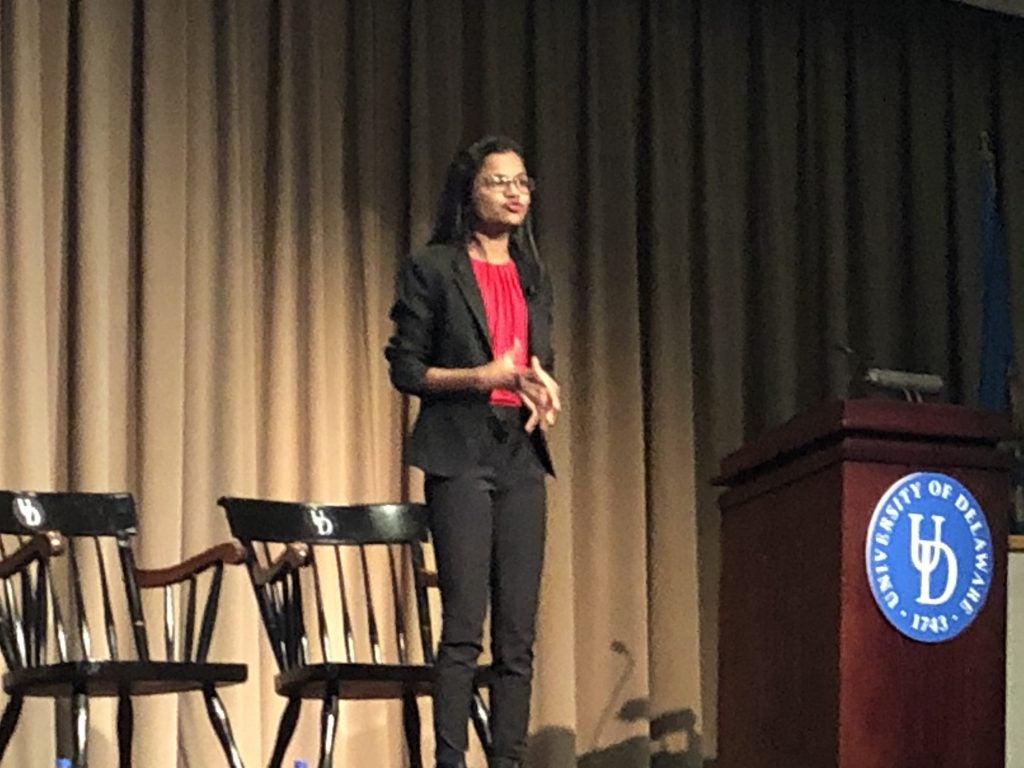

Neha Das, a junior at Charter of Wilmington, says the disparity is unsettling.

Das is a fairly typical Charter of Wilmington student. She’s Asian, like 30% of the student body, and lives in an affluent suburban neighborhood. She scored 1500 on her SATS, including a perfect 800 in math.

She realizes most students from Wilmington can only dream about attending a school like hers.

“Charter has almost created a bubble around itself and kind of made it hard to penetrate for low-income students, African American students,’’ Das said. “Even though I conform to it, I can definitely see there’s a flaw in what I’m doing and what I’m engaging in. But me and other students similar to myself are just trying their best to succeed in the system that we were given.”

A handful of other predominantly white and selective charter and magnet schools are located a few miles from the city. There’s Conrad Schools of Science, Odyssey Charter School and Delaware Military Academy, to name a few.

The sole survivor of the original three high schools is Howard, but it’s now a vocational-technical school, albeit one that has been expanded and modernized.

Almost all 900 Howard students are Black or Latinx, and about a third are Wilmington residents, state statistics show.

Though Howard’s academic proficiency is low, it’s a training ground for carpenters, mechanics, cosmetologists, chefs and medical and legal aides. Sports are big at Howard, which won the Division II state football title this year.

Rahsaan Matthews, Howard’s student adviser and head basketball coach, has family ties there.

“Howard is a pillar of the community,” Matthews said. “My parents and family came through it so there’s still a lot of respect for the traditions set forth in the past. And as an employee of here, I’m excited to be carrying that torch for the future.”

Besides Howard, Wilmington has two other public high schools — Freire and Great Oaks. Both are fledgling charters that struggle academically and about 9 in10 students are black or Latinx.

While public high school is the only option for most Wilmington students, Erica Dorsett’s son Elijah Jones found a way out.

Jones attended Wilmington’s Thomas Edison Charter elementary school, which serves a large number of low-income families, and received a high school scholarship to Tatnall, a private school in Greenville that costs $29,000 a year.

“I think that I’m better for it,” said Jones, who wants to attend law school and work for the United Nations. “I think that because the world looks like Tatnall and the places that I want to go and the spaces that I want to infiltrate because the spaces weren’t designed for me.”

The bottom line for Jones, he said, is equity in opportunity.

“We shouldn’t have to fight so hard to equally distribute a quality education,’’ he said. “We’re not fighting a war here. It only makes civic sense to teach every child the way a child should be taught.”

‘We don’t know each other’

If a traditional public school was to return to Wilmington, where could it go?

How about P.S. duPont?

It’s a grand structure on the city’s north side that recently had a $44 million overhaul. It’s now a middle school in the Brandywine District.

Brandywine board president Ralph Ackerman pondered whether P.S. could be home to the reincarnation of the city high school some desire.

“Would Brandywine be willing to give up that crown jewel?” he asked.

“I think we’d have to have a conversation about that, but I think we’d be supportive of efforts to help the city and help the residents become a unified whole and not be this fragmented situation where they are broken up like an apple pie and cut into multiple pieces.”

Jerry Clifton, who is now the mayor of Newark, has another idea: two city high schools, one in west Wilmington and one in east Wilmington.

“I think two smaller high schools where they have the high school football rivalry on Thanksgiving like we had would work wonders to bring back that sense of community that we lost over the years with our younger people being dispersed to literally the four winds, the four districts,” Clifton said.

A traditional school also makes sense to Woodland, the Cab Calloway senior and Wilmington resident.

“I mean, we all live around each other, but we don’t know each other,” he said. “Why? Because we’re all going to different schools. We’re all being spread out. And it would definitely build the community, the Black community, being in the same school.”

Purzycki said a city high school is simply in the public’s interest.

“Almost everybody else has a stake in a better school system in our state,’’ the mayor said. “And I really believe in the end, that a well-run, well-financed Wilmington High School is going to be better for everybody.”

There is one critical factor he suspects has held back Wilmington High’s resurrection.

It’s the idea that the school would be almost 100% Black.

“The resistance to resegregation is what’s basically kept this situation in place today,” Purzycki said.

‘Friday Night Lights are not going to save the city and education’

Not everyone agrees that Wilmington needs a traditional public school.

“I think in a perfect world, we have those schools that are close by and that’s the allure of a Wilmington High School for many of the people we talk to,’’ said Atnreakn Alleyne, who runs the education nonprofit Delaware Campaign for Achievement Now.

“But beyond that piece, I think our first and foremost priority is that the school is just amazing, whether it’s a vocational school, magnet school, charter or public school, whatever.”

Alleyne said nostalgia shouldn’t be the impetus for the rebirth of a traditional public high school.

Kendall Massett, head of the Delaware Charter Schools Network, agrees.

“Friday Night Lights are not going to save the city and the education. It’s just not,’’ said Massett, who suggests policymakers focus on improving early and elementary education.

“Our biggest issue is that our kids are coming to high school sometimes two, three, five or six years behind,’’ Massett said. “That’s unacceptable, completely unacceptable.”

Consortium ponders return of Wilmington High

Sen. Lockman, who represents one of Wilmington’s poorest areas, has a broad perspective on the education conundrum.

Lockman grew up in a comfortable home in Wilmington, but instead of going to a private or charter school, she attended her assigned high school just outside the city — Alexis I. du Pont. Her 16-year-old daughter initially went to traditional public schools, but is now at Charter.

Lockman realizes the split district/choice/charter system has led to segregation “on a level that’s probably beyond what we experienced before we had those mechanisms available to us.

“So while there are benefits to many individual families and students that are wonderful — I’ve taken advantage of them — I think we really have to be mindful of the way they have aggravated inequities as well, and so they’ve led to concentration of need and poverty and made it difficult for us to provide services for those students.”

The Redding Consortium that Lockman now co-chairs is looking to change the alignment that Wilmington split among four districts.

Whether the groundswell of support in some quarters will lead the politicians, academics and advocates to recommend bringing back a Wilmington High remains to be seen, but Lockman sees value in that proposition.

“To have one could potentially be a great asset to the city of Wilmington and all those fun, sportsy, rah-rah things that come with it,’’ the senator said. “Absolutely!”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.