Work of groundbreaking musician Julius Eastman revived in Philly concert

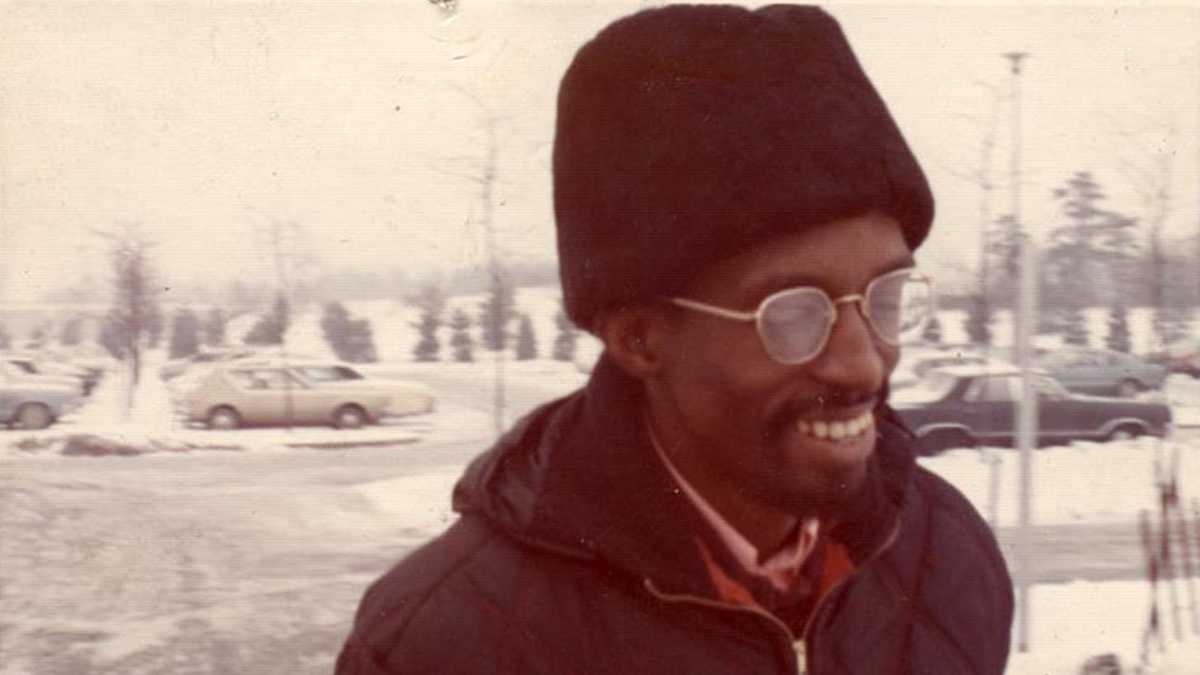

Eastman in Buffalo (Photographer Unknown)

The music of a black, gay, avant-garde composer — largely forgotten for 30 years — will be revived in West Philadelphia Friday night.

Julius Eastman, in his day, was a trailblazing figure in the avant-garde. Trained at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia in the 1960s, Eastman was influenced by John Cage and Morton Feldman, who revolutionized music by allowing for chance and accident. He became an important presence in New York’s downtown music scene.

“He was always an outrageous person. He pushed a lot of envelopes. He was a gay, out-front human being,” said Joseph Kubera, a pianist who played with Eastman in the 1970s. “He did a theater piece in the late ’60s where he simulated sex with the double bass.”

Eastman even managed to anger John Cage — the impishly unflappable pioneer of postmodern music — by taking outlandish liberties while performing Cage’s “Songbook” in the 1975.

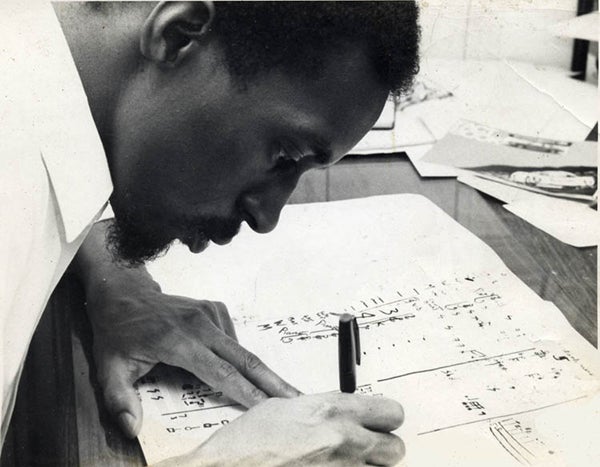

Eastman composing (Photo by Donald Burkhardt)

Eastman composing (Photo by Donald Burkhardt)

The titles of his minimalist pieces paint him as a provocateur. One of the most provocatively titled, including the N-word, is an hour-long piece written for four pianos, will be performed at the Rotunda in West Philadelphia.

“He took that term to mean ‘That which is fundamental,’ to use his words,” said Kubera. “He made references to the basicness of the experience of being a slave, being a people on whose back the country was built. He was much better at explaining it than I am.”

It starts with four pianists on four pianos, culminating with 24 hands: three players per piano.

Through a series of unfortunate events, involving both bad luck and bad decisions, Eastman was evicted from his apartment in New York. All his musical scores were seized by the sheriff and thrown away. He was homeless, living in Tompkins Square Park, and ultimately died alone in a hospital at age 49.

He had so alienated himself from his downtown colleagues that eight months passed before his obituary appeared in the Village Voice.

Now, very few of his works can be performed, because nobody knows how to play them. Only fragments of written scores exist.

Dustin Hurt of Bowerbird, a new music presenting organization, has been digging up those fragments and piecing them together. He discovered that many pianists who played with Eastman had saved their scores after the performance.

A few recordings exist, but the nature of the music makes transcribing the recordings into sheet music impossible. The multilayered, sometimes redundant cycles of repeated notes build into a wall-of-sound effect that cannot be picked apart.

“He used nontraditional notation,” said Hurt. “As far as we can tell, it’s peculiar to every piece. Every piece has its own notation system.”

The Friday night concert is a taste of what might come later. With the help of a grant from the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, Hurt is trying to cobble together enough finished scores to fill out a longer festival of Eastman’s work.

“The music I heard was amazing, but the fact that there was more to be heard — can we find it?” said Hurt. “Can we rebuild it so we can hear it again?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.