With a ceremonial mortgage burning, the Paul Robeson House marks its next chapter

With the debt burden lifted, the West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance is one step closer to adding programming to attract younger people to the house and museum.

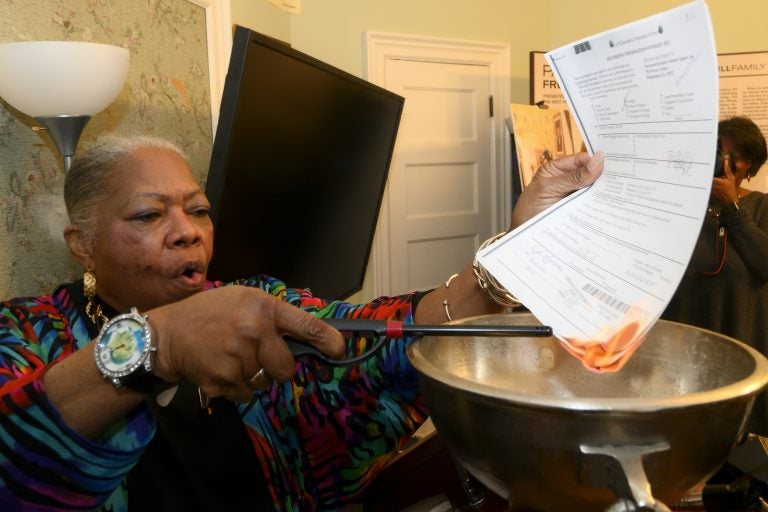

Paul Robeson House Executive Director Vernoca Micheal lights the house's mortgage during a ceremonial burning on Saturday, Jan. 25, 2020. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

When Vernoca Michael took over as executive director of the West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance and the Paul Robeson House & Museum in 2015, she had two goals: make the necessary repairs on the twin rowhouses at 4949-4951 Walnut St. — and pay off the mortgage.

Michael, along with dozens of other museum volunteers and neighbors, celebrated the latter achievement Saturday with a ceremonial mortgage burning at the Robeson House in the Walnut Hill neighborhood.

Setting the stapled document aflame and watching it burn in a metal chalice, Michael thought of her predecessor, Frances Aulston, and the work she did to get the volunteer-run Paul Robeson House to this point.

After the burn, they played “Ol’ Man River,” which Robeson sang in the musical “Show Boat” — in 1927, one of the first Broadway musicals to tackle racism in the United States. The song contrasts the struggles of Black Americans with the never-ending Mississippi River.

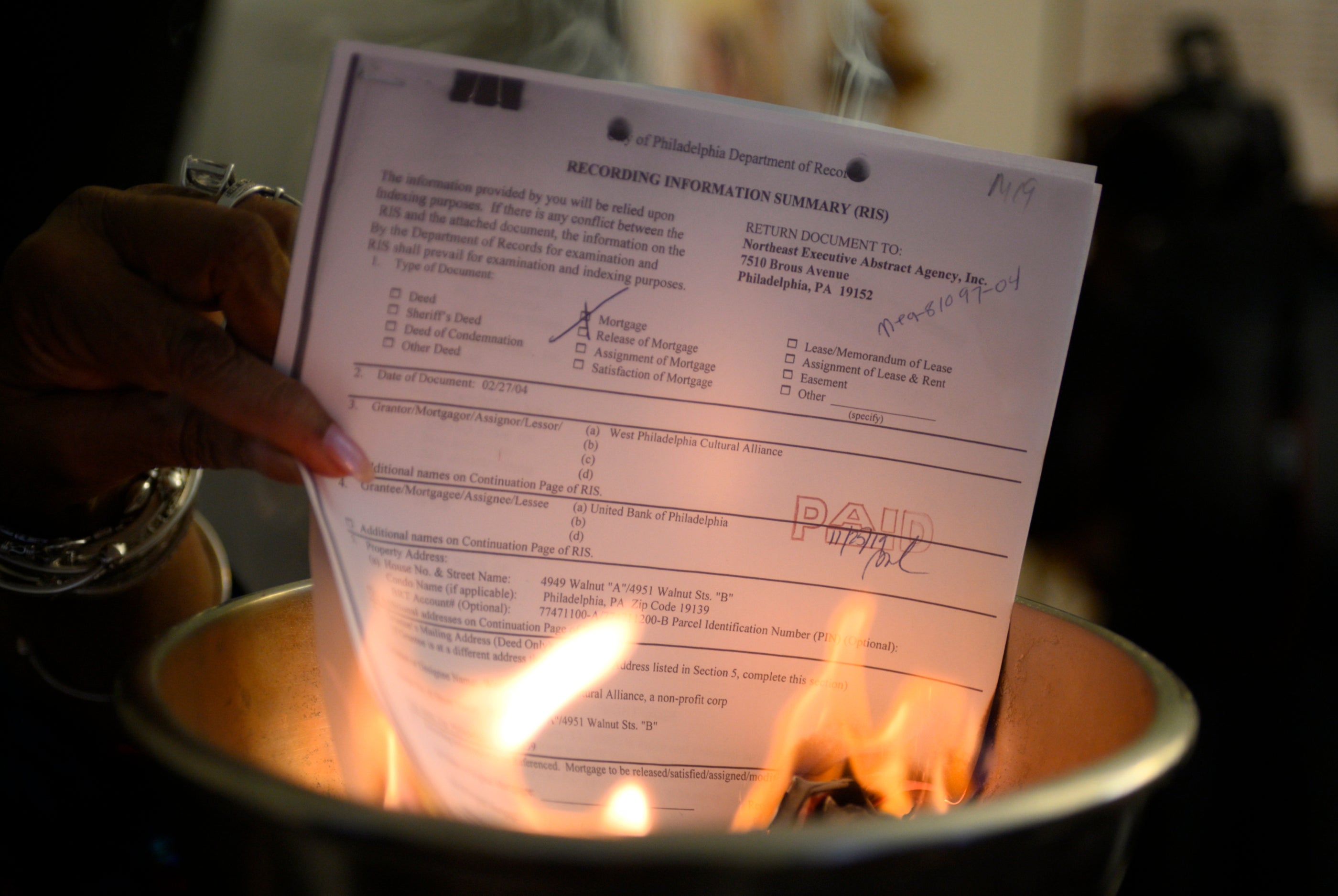

“Today, we burn the mortgage on these two properties,” Michael said. “We are meeting the goal that Frances Aulston set for us. We are now recognizing that it could be done, and it is being done.

“And, as those of you who can see, it’s marked paid,” Michael added, to laughter from the crowd.

For Michael and many others who consider the legacy of Robeson — actor, singer and civil rights activist — an important one to carry on, the mortgage burning brought them one step closer to funding programming to teach the young and old of West Philly and beyond the values that mattered most to him.

His local roots

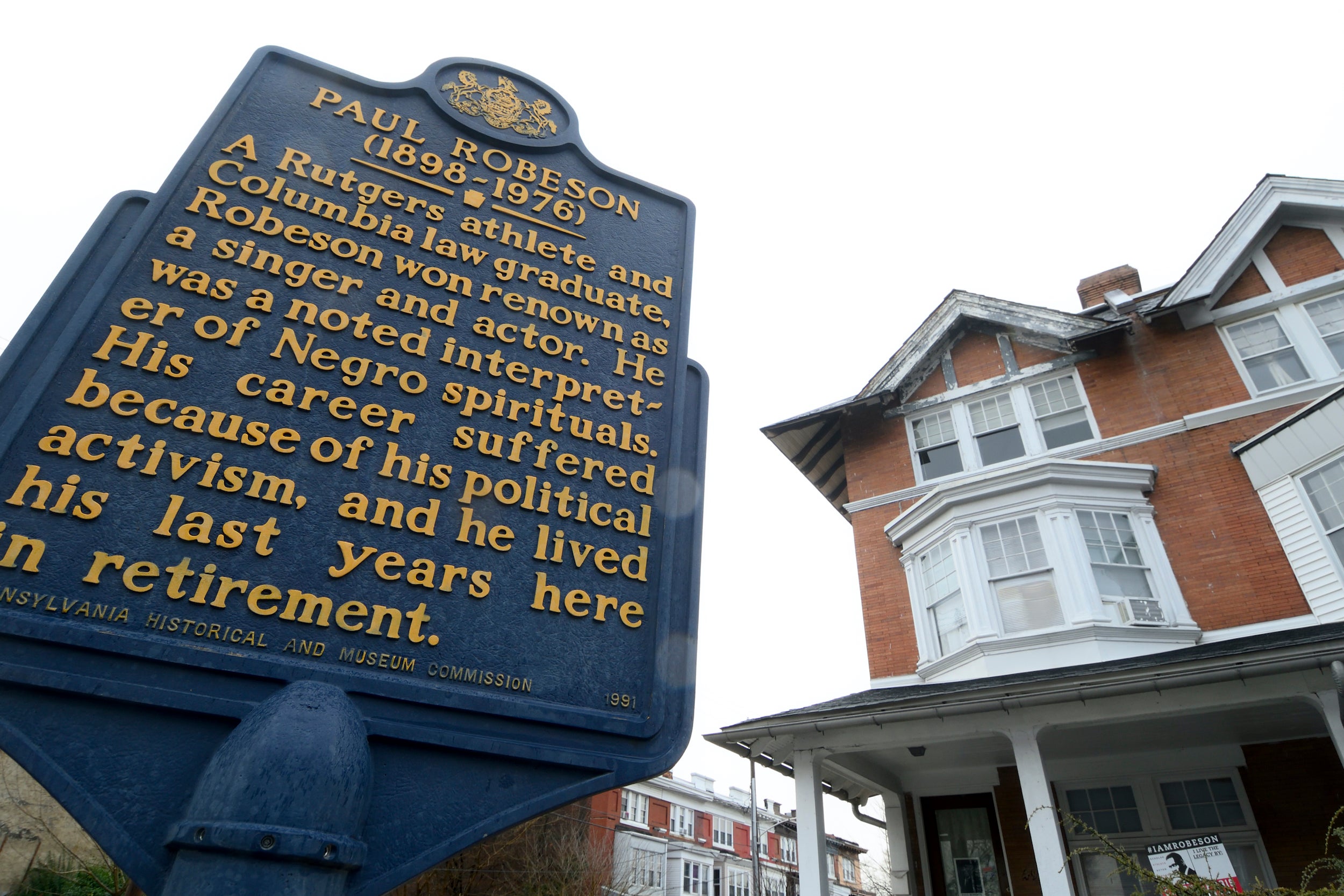

Robeson, born in Princeton in 1898, is remembered for his distinct bass baritone voice. Considered an artist of the Harlem Renaissance, he was well known later in his career for his acting in “Sanders of the River” and “The Proud Valley” in the 1930s and ’40s.

In 1950s’ era of McCarthyism, Robeson was blacklisted because of his visits to Moscow and his socialist leanings. He was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 after he refused to sign an affidavit confirming he wasn’t a communist. He was then asked by the committee why he didn’t stay in the Soviet Union.

“Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I’m going to stay here and have a part of it just like you, and no fascist-minded people will drive me from it,” Robeson said.

After his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson, passed away in 1965, he moved and spend the last decade of his life at 50th and Walnut streets, living with his older sister, Marian Forsythe.

That was how Vernoca Michael first got to know her “Uncle Paul,” though there was no blood relationship.

Michael lived across the street, and her parents were close to Forsythe and Robeson — her mother, a concert artist, would often vocalize with Robeson. She became the unofficial driver of Forsythe and Robeson while she was a student at the University of Pennsylvania.

“One of my favorite things about Uncle Paul was when I would walk in the front door and he would always bow to me, and I was just thrilled to think that just my uncle, not so much being this worldwide entertainer, my uncle would bow to me,” Michael, now 74, recalled.

Many years after the siblings’ deaths, Michael fostered a relationship with West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance founder Frances Aulston. A librarian with the Free Library of Philadelphia, Aulston created the organization in 1984 to bring more arts programming to the community.

In the early 1990s, Aulston learned that the Robeson House — owned by Forsythe’s daughter Paulina until 1994 — was for sale. The Cultural Alliance took an interest in the property as it was looking for a new administrative space.

Knowing Robeson’s powerful impact on civil rights, Aulston envisioned the house becoming an art mecca for West Philly. She used her life savings of $7,000 and $30,000 in funds raised by the Cultural Alliance to put a down payment on the house. That same year, the owner of 4949 Walnut St. next door passed away, leaving the right of first refusal to the new owners of Robeson’s former home.

For the next 20 years, Aulston worked on the house — which was in need of serious renovations — as well as collecting photos and artifacts to create the museum. The house was designed a National Historic Landmark in 2000.

Most of the renovations were completed in 2015, the year Aulston died.

The house’s future: Attracting Gen Z and millennials

Prior to her passing, Aulston expressed fears of someone else taking over the property. As a friend of Aulston’s, the executive director position sort fell into Michael’s lap 4 ½ years ago.

Last year, she and others set up a crowdsourced Plumfund to raise money to pay off the mortgage, which donations helped accomplish in October.

Having the mortgage paid off has lifted a serious weight from her shoulders, Michael said, but she’s already thinking ahead to other much-needed repairs within their administrative space next door. Among those are floor repairs, painting, plastering, and some electrical and wiring work. They’re hoping to raise $50,000 this year to pay for those improvements, as well as renovations to the exterior of the Paul Robeson House.

Another big goal of Michael’s? Getting Generation Z and millennials interested in learning who Robeson was and about his cultural impact.

“It’s important for us to recognize our history and remember our history,” said Michael, who was also previously the owner of the historic North Philly boxing club, the Blue Horizon. “I’m interested in making sure that this house is carried on for Fran’s sake, and so that we can keep Uncle Paul’s legacy alive.”

That’s why she’s brought on a younger program director to help spark interest in the house among those two generations. Christopher Rogers, a volunteer with the Robeson House since 2015, is currently pursuing his Ph.D. in literacy at Penn.

This year, the Robeson House is hosting a number of events that cater to people of different ages and backgrounds. On Saturdays, We R.E.I.G.N. — a mentor group focused on empowering Black girls — hosts its workshops at the house. And Rogers hosts the Philadelphia chapter of Noname’s Book Club. Created by hip-hop artist Noname, the club meets monthly to discuss books from her listings, which is made up of all authors of color.

Rogers said it’s a way to help connect many of the young Black activists in Philadelphia with a place that’s tightly connected to the civil rights struggle.

“We see a relationship between taking people who are already out in the streets protesting many of the issues that the Black community has faced for a long period of time and really letting people know about the history of struggle in the United States,” Rogers said. “So the Robeson House is a perfect place to be able to do that.”

Physically preserving Robeson’s impact

Sherry Howard is a volunteer with the Paul Robeson House. Over the years, she’s helped Michael organize many of the pieces inside the museum and donated a number of books, cabinets and display cases.

She said paying off the mortgage is a major milestone for the historic house.

“Especially for Black people and Black organizations, ownership is very important because there was a time when we couldn’t afford to own anything,” Howard said. “We are one of the few groups that are able to say this is ours.”

Although there’s a long way to go with renovation work to the 4949 Walnut St. property, she said, the most positive outcome remains that Robeson’s legacy will live on.

“Because he lived here, he brought with it the stature of himself and what he stood for,” Howard said. “So the house is like a living legacy of Paul Robeson and who Paul Robeson was, so when you preserve the house, you preserve the life and legacy of the particular man.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.