Wilmington Fire Department still using rolling bypasses that lawyer blames for 3 firefighter deaths

Wilmington takes fire equipment out of service to save money. That policy will become the focus of a lawsuit over three firefighters' deaths.

Listen 2:04

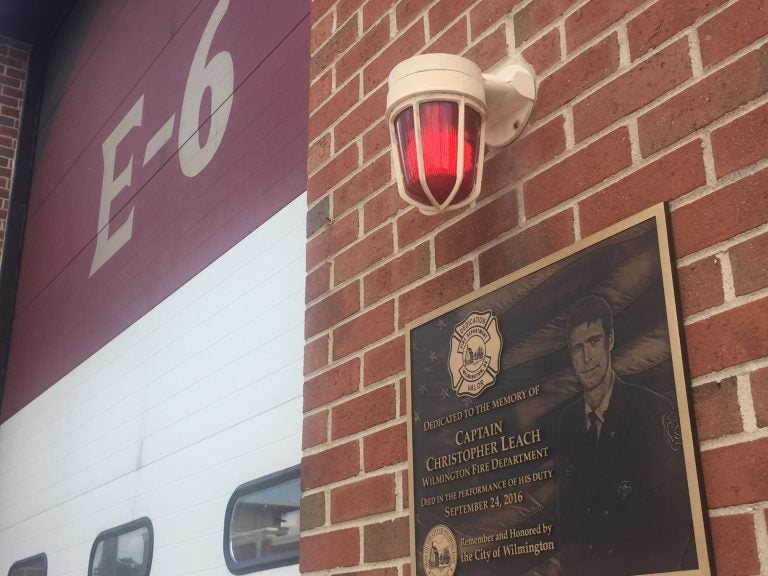

A plaque dedicated to Christopher Leach, one of three Wilmington firefighters killed in a September 2016 fire, is affixed to Station 6.. The term E6 refers to Engine 6, water-carrying truck that normally operates out of the station, but was mothballed the night the trio died while battling the blaze. (Cris Barrish/WHYY)

When the first firefighters arrived on the scene of a roaring late-night house fire in Wilmington, Delaware, nearly two years ago, they were ahead of the truck carrying 750 gallons of water.

That’s because the city had mothballed that “engine” truck at the station closest to the blaze that night. Known as rolling bypasses, brownouts and blackouts, it’s a practice Wilmington has used periodically over the last two decades to save money on manpower.

Bypasses remain in effect today.

On the night of the September 2016 fire in Canby Park, several firefighters entered the two-story row home to search for possible trapped victims before water could be trained on the building to significantly knock down the flames. That decision proved fatal when the first and then second floors collapsed.

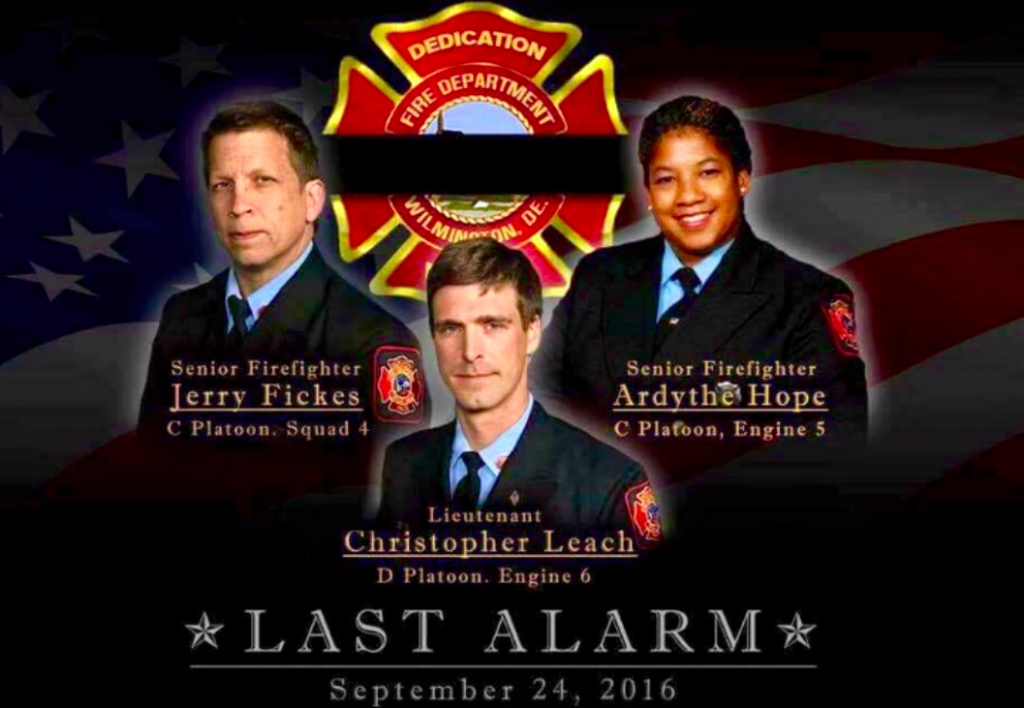

Three veteran firefighters – Christopher Leach, Ardythe Hope and Jerry Fickes — lost their lives as they were buried under falling, flaming debris. Three others were injured.

A 27-year-old woman who lived in the house is facing murder, arson and other charges for allegedly setting the fire.

While the results of a federal investigation into the deadly fire haven’t been released yet, the lawyer for the late firefighters’ families blames the rolling bypasses.

“Wilmington has a policy of denying necessary water to the scene of any fire, and it’s getting there minutes later, when seconds count,’’ said attorney Thomas S. Neuberger, who plans to file a lawsuit against the city.

“Firefighters say that if you have a fire, put water on the fire, and problems go away. But you have got to have water, and Wilmington is not putting water on them,” he said. “This is a deliberate policy, and they are going to be held responsible.”

The Canby Park fire was located just under a mile from the station at Second and Union streets.

According to Neuberger, who has been conducting his own investigation for months, a ladder truck that doesn’t carry water or hook up to a fire hydrant was dispatched from that station. The closest station with an engine truck in operation was at least two miles away.

Leach, who was on the ladder truck that arrived on the scene first, reported heavy fire in the rear of the home, Neuberger said. The initial erroneous report was that people were trapped inside.

Leach and other firefighters entered the home about 3:06 a.m. as others began blasting water to the front of home, even though the fire had started in the basement at the rear of the home, Neuberger said.

The first floor collapsed at 3:09, and the second floor at 3:18, Neuberger said.

City Councilman Bob Williams, the Public Safety Committee’s vice chair, and fire union president Kevin Turner said they are withholding judgment on the reasons the three firefighters died while they await the results of the probe by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. An agency spokesman said that report should be finished and made public later this month.

But both Turner and Williams, a former police officer, agree that the continued use of rolling bypasses puts residents and firefighters in danger.

“Rolling bypasses put the area in which the engine is closed in jeopardy,’’ Williams said. “Meaning that the engine is the vehicle that carries water to the fire. But if that piece of apparatus is shuttered because of financial constraints, those seconds and minutes delay the actual extinguishing of the fire.”

Turner, who heads Wilmington Firefighters Association Local 1590, said the bypasses stopped briefly after the September 2016 fire under then-Mayor Dennis Williams and Fire Chief Anthony Goode. They have resumed under Mayor Mike Purzycki, who took office in 2017, and his chief, Michael Donohue.

“We’ve been opposed to brownouts since the Wilmington Fire Department started this to save money,’’ Turner said. “Obviously, we believe it’s detrimental to the safety of our citizens and our firefighters.”

“The city may argue that it doesn’t affect public safety. However it does affect response times and also reflects the fact that we lack the resources to extinguish some of these fires — and even rescue some of our firefighters.”

Wilmington continues using bypasses even as other departments have stopped doing so. In 2016, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney halted the city’s nearly six-year practice of using rolling bypasses after a city controller’s report found that the policy “only exacerbated the department’s already underachieving response to fire emergencies,’’ increased costs and jeopardized public safety.

Purzycki, whose administration has cut the authorized number of firefighters from 172 to 156 last year, wouldn’t agree to an interview for this story.

Donohue, who replaced Goode, said during a brief phone conversation that while the bypasses remain in place, the city is planning a training academy for rookie firefighters soon so they can stop the practice, which would be early next year at the soonest.

Donohue scheduled an interview to discuss the issue in depth, but Purzycki spokesman John Rago later informed WHYY that the interview was canceled. Rago cited the pending lawsuit as the reason the city law department advised against any interviews.

WHYY also filed a Freedom of Information request on July 25 for details about the bypasses, staffing, overtime costs and other related issues. The city has not yet provided any information, nor has the Purzycki administration responded to several questions submitted by WHYY.

A handful of city residents who live near the Lakeview Road home, since torn down, where Leach, Hope and Fickes were killed, said they were unaware that rolling bypasses were in effect that night — and that they are still in use.

They agreed, however, that the practice should stop.

Jose Barazza, who lives behind the house and saw the flames from his own porch that fateful night, wondered if the city was literally playing with fire.

“It can happen again,’’ he said. “Is that going to be the same problem?”

The city’s six fire stations, he said, are “supposed to be working all the time, 24 hours a day.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.